February 1960

Sit-ins in Greensboro

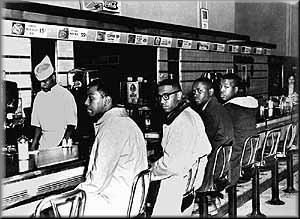

“Negroes get food at the other end.” The white waitress pointed to the other side of the counter, where there was no seating. In 1960, like many establishments across the South, Woolworth’s Department Store in Greensboro accepted money from Black customers but expected them to leave the store–the seats were for whites only. In defiance, four North Carolina A&T freshmen sat down and refused to move until closing time.

A&T students at Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, 1960, Copyright (Greensboro) News & Record.

On February 1, 1960, 18-year-olds Ezell Blair Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin McCain, David Richmond, and Joseph McNeil put their dorm room “bull sessions” into action. McNeil remembered, “We would get together and discuss current events, political events, things that affected us–pretty much as college kids do today… The question became, ‘What do we do and to whom do we do it against?’”

Blair’s personal experience added immediacy to these discussions. Returning to campus on a Greyhound bus after Christmas break, he had been denied service when he sought food at a Greyhound bus station. Woolworth’s, they decided, “seemed logical because it was national in scope and somehow we had hoped to get sympathies from without as well as from within.”

The Greensboro sit-ins were a spark in a blazing movement for civil rights, but they weren’t the first to happen the South. In April 1943, Pauli Murray led some of her Howard University classmates in a “stool sitting” at the segregated Little Palace Cafeteria in Washington, D.C. On June 23, 1957, at the Royal Ice Cream Parlor in Durham, Reverend Douglas Moore and six others were arrested for sitting in the whites-only section. CORE led sit-in campaigns in St. Louis in 1949, then in Baltimore in 1953. Greensboro itself had a history of direct action segregation protest, when NAACP president George Simpkins and a few friends were arrested while playing a round of golf at the city-owned Gillespie Golf Course in 1955.

Following the first Greensboro protest, the original four students grew to 27 on the second day, and 63 students on the third day. The mass of protesters “occupied almost every seat” so that no seating was left for white patrons. The protesters included four women from Bennett College, the historically Black women’s college near A&T, who had been strategizing about direct action protests in the community over the past year. Dr. Esther A. Terry, a Bennett student at the time, recalled “we went downtown wearing hats, and we wore gloves, and we were Bennett ladies… it was just such a jarring thing to be told, ‘Well, Bennett Lady, guess what? You can’t sit down there and have a cherry Coke.’”

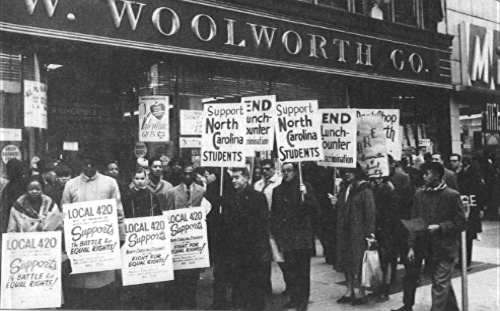

The Greensboro sit-ins inspired mass movement across the South. By April 1960, 70 southern cities had sit-ins of their own. Direct-action sit-ins made public what Jim Crow wanted to hide–Black resistance to segregation. By directly challenging segregation in highly visible places, activists grabbed the attention of the media. In Nashville, where activists had engaged in nonviolent workshops with James Lawson since 1959, SNCC leader Diane Nash remembered “being in the dorm any number of times and hearing the newscasts, that Orangeburg had demonstrations, or Knoxville, or other towns. And we were really excited…The movement had a way of reaching inside you and bringing out things that even you didn’t know were there.” The sit-ins told Black youth that they had power to capture national attention. “Before seeing these sit-ins,” SNCC’s Charlie Cobb said, “Civil Rights had been something grown-ups did.”

Sources

William H. Chafe, Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 85.

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2008), 97-99.

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996), 77-79.

Interview with Jibreel Khazan and Franklin McCain by Eugene Pfaff, October 20, 1979, Greensboro Voices Collection, UNC-Greensboro.

“Charlie Cobb Discusses the Freedom Movement” February 2009, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.

“The Greensboro Sit-ins,” Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.