Amelia Boynton

Amelia Boynton speaking to audience at Brown Chapel in Selma, Alabama, May 10, 1966, Jim Peppler Southern Courier Collection, ADAH

August 18, 1911 – August 26, 2015

Raised in Savannah, Georgia

When SNCC’s Bernard Lafayette and his wife Colia Liddell came to Selma, Alabama in the fall of 1962, they found Amelia Boynton and her husband Samuel William “S.W.” Boynton ready and primed for action. They had been working for change long before the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Amelia Boynton had come to Selma, Alabama as an agricultural extension agent in 1929 where she met and married her co-worker S.W. and used their government positions encourage Black people to register to vote and buy land. We “would have meetings in the rural churches, and even in homes,” Boynton explained, “And we would show them how to fill out these blanks, how to present themselves when they went down to the registration office.”

Amelia Boynton grew up in a two-story wooden house in Savannah, Georgia, where her father owned a wholesale wood lot. “We felt like we had to be leaders, because this is what the community expected,” Boynton said, recalling of her childhood. Her introduction to politics came as a ten-year-old when traveling by horse and buggy she accompanied her mother–a committed women’s suffragist–“knocking on doors and ringing doorbells, giving women the proper information, taking them to the registration board and/or taking them to the polls to cast their votes.”

After studying home economics at Tuskegee University, Boynton began working as the home demonstration agent in Dallas County. There she met and married agricultural extension agent, S.W. Boynton. They traveled down dusty dirt roads deep in the rurals and backwoods of the county teaching Black people better methods for farming but also “how to gain political, financial, and educational strength.” As Mr. Boynton often said, “Ownership makes any man respected. Living on the plantation makes a man’s family a part of the owner’s possession.” In addition to their demonstration work, the Boynton’s operated a insurance agency, real estate office, and employment agency out of their office on Franklin Street, located directly across from the city jail.

In the mid-1930s, Amelia and S.W. Boynton began working with and revitalizing the moribund Dallas County Voters League. Its handful of members met in the back room of their office, working to get more Black people on the voting rolls. When SNCC’s Bernard Lafayette and his wife Colia Liddell arrived in Selma, Amelia Boynton offered them space. “Rather than open a new SNCC office,” Lafayette explained, “I assigned myself to become the staff person for the Dallas County Voters League.” The Boyntons were staunch advocate of SNCC’s efforts. It was Mr. Boynton’s passing in May of 1963 that sparked the very first mass meeting in Selma.

In 1964, Amelia Boynton became the first African American woman in the state of Alabama to run for Congress, challenging a white incumbent the Alabama Fourth District seat. The campaign motto, hung in her office window, was “A voteless people is a hopeless people.” Despite being defeated, she earned eleven percent of the local vote, where only five percent of Blacks were registered.

That summer, an injunction brought local demonstrations to a halt. Mrs. Boynton reached out to SCLC, inviting them to come to Selma and invigorate the local movement. On January 2, 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. kicked off a nationally-geared campaign for voting rights in Selma, and Boynton again worked wholeheartedly to drum up local support. Her home on 1315 Lapsley Street housed a consistent stream of movement activists. “People run in and out all the time,” she said.

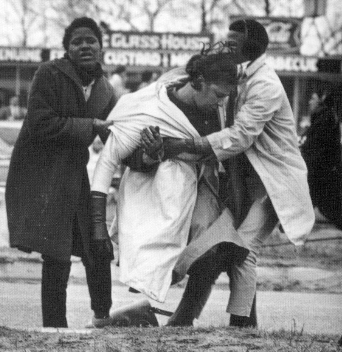

On March 7, 1965–Bloody Sunday–Amelia Boynton marched in the first rows of a line of six hundred protesters, crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge headed for Montgomery. “I saw in front of us a solid wall of state troopers, standing shoulder to shoulder,” Boynton remembered. Gas masks covered their faces, and they held billy clubs, cattle prods, guns, and gas canisters. When the marchers refused to turn around, the troopers advanced. Boynton was tear gassed and beaten unconscious.

Two weeks after she was released from the hospital, she sat on the platform in Montgomery as Martin Luther King addressed a crowd of thousands. In 2015, Amelia Boynton crossed the Edmund Pettus again, this time on the fiftieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday, a celebration to her lifelong dedication to the struggle for freedom.

Sources

David Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (New York: W. Morrow, 1986).

Bernard Lafayette, Jr. and Kathryn Lee Johnson, In Peace and Freedom: My Journey in Selma (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2013).

Amelia Boynton Robinson, Bridge across Jordan (Washington, D.C.: Schiller Institute, 1991).

Sue Cronk, “In Alabama Primary, Negro Woman is a Candidate,” Washington Post, March 11, 1964, MFDP Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Interview with Amelia Boynton Robinson conducted by Blackside, Inc., December 6, 1985, Eyes on the Prize, Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries.