Penny Patch

December 1943 –

Raised in New York, New York

Young people challenging other young people to become part of the southern movement was an important dimension of SNCC. And it was not confined to race or southern geography. Penny Patch was a white student at Swarthmore College during the early 1960s. At a protest while still in school, she met SNCC organizers Reggie Robinson and Dion Diamond, who were recruiting students to work on southern voter registration and direct action projects. Patch immediately volunteered but was told that SNCC was mainly looking for black students.

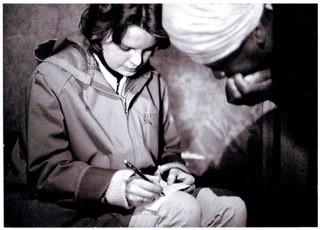

Photograph of Penny Patch in Panola County, MS in 1965 by Tamio Wakayama, Used with the permission of Tamio Wakayama

A few months later, however, Patch got a phone call. Charles Sherrod had organized an integrated field project in Southwest Georgia. All she knew about the South was what she had read in Gone With the Wind. Without asking her parents for permission, Patch became the first white woman working on a SNCC field project in the Deep South in June 1962. She was eighteen. When the Movement presented itself “right smack in [her] face,” Patch recalled, she didn’t think twice. “Being a bystander was simply not an option.”

In Southwest Georgia, Patch “learned to cook, type, and do office work. [She] also learned to drive a car, listen and persuade, develop strategy, organize people to register to vote and go on demonstrations, act independently if necessary, speak in public, and keep working despite fear and exhaustion.”

After just a few weeks in the field, her awareness of herself as one of the few white people quickly faded. “The sensation for me was of melting into the crowd. If I looked at other people, which is more often what I was doing, then I would see people just like me. Or rather, what happened is that I came to feel that I looked just like them.”

Patch’s role as a fieldworker in the Deep South was an experiment and did not come without its challenges. She faced intimidation and threats from whites in southern communities, but her status as a white woman afforded her a degree of protection from many assaults by whites. At the same time, her presence often put others in physical danger. In 1962, while living with Mama Dolly Raines on her farm, Patch was asked to leave. Mama Dolly had been receiving threatening phone calls in response to the white woman who was staying with her, and it was decided it would be best if Patch relocate to a more neutral location.

Such moments were painful for Patch, but as she later recalled, “it was all part of my education about the limits my whiteness placed on my usefulness, and I was struggling so hard to grasp that if I wanted to do this work, I was going to have to subordinate my personal needs.”

After her time in SNCC, Patch went on to focus on maternal health, working as a nurse midwife in rural communities. Throughout her life she has also continued to lead and participate in racial justice work within and outside of her own community.

Sources

Wesley Hogan, Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC’s Dream for a New America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

Penny Patch, “Sweet Tea at Shoney’s,” Deep in Our Hearts: Nine White Women in the Freedom Movement, edited by Constance Curry, et al. (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2000), 131-170.

Penny Patch, “The Mississippi Cotton Vote,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 403-409.