Carrie Dilworth

August 29, 1899 – June, 1979

Raised in Gould, Arkansas

Carrie Dilworth’s decades of work helped lay the foundation for SNCC’s organizing in Gould, Arkansas. Working with the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU), she helped organize a statewide cotton picker’s strike during the 1930s. It was dangerous. To spread the word about the strike, Ms. Dilworth laid down on the floor of a car, opened the door slightly and slipped fliers through the crack. The fliers scattered across Arkansas backroads, and by the morning, “white folks thought it was a plane that distributed fliers.” Sharecroppers went on strike in three counties, forcing the landowners to raise their wages from forty to seventy-five cents a pound.

Ms. Dilworth spent the next decades working with the National Farm Labor Union and the NAACP. In 1963, Ms. Dilworth encouraged her neighbors to welcome SNCC. She invited SNCC field workers to join her and introduced them to families as she distributed goods to those in need. The old STFU food co-op became SNCC’s headquarters in Gould.

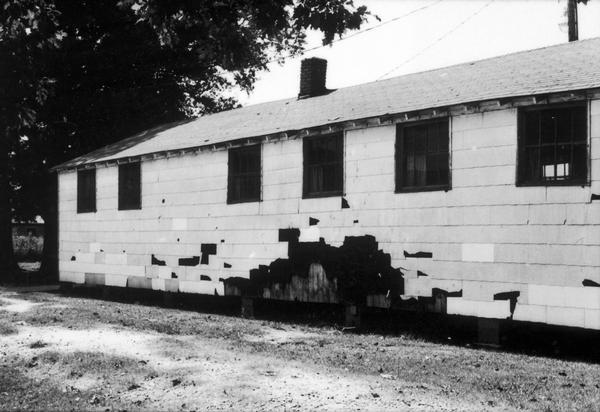

Along with voter registration, school integration became the focal point of SNCC’s work, and Ms. Dilworth led a march to the federal courthouse in Little Rock protesting school segregation. In Gould, the Black high school was dilapidated. The library only had thirty books, and the district paid Black teachers $600 less than white teachers. Gould’s white establishment tried to block integration at every turn.

Eventually, the Gould School Board agreed to let a few Black students to attend the white school. However, on the first day, sixty Black students went to the white school and only half of them were allowed to attend classes due to “overcrowding.” The Department of Education refused to intervene, and Gould’s schools remained segregated.

Ms. Dilworth became a plaintiff in a lawsuit filed by the Gould Citizens for Progress. She sued the school board on behalf of her grandchildren who weren’t allowed to attend the white school.

Meanwhile, SNCC faced new challenges and dangers in Gould. In 1966, SNCC’s Freedom House was burned down. A year later Ms. Dilworth entered the race for mayor but lost the election. By this time, SNCC had begun to question the goal of integration. Children who attended the white school weren’t welcomed by their teachers or classmates and missed the familiarity of the Black schools. In 1968, Ms. Dilworth’s case against the school board finally reached the Supreme Court and in a unanimous decision, the judges ruled in favor of integration.

Ms. Dilworth remained grateful for SNCC’s work in Arkansas despite the setbacks and challenges. “They’re a big help to the people down here,” she remembered, “I’ve been living here 65 years and I ain’t had no one help me like that.”

Sources

H.L. Mitchell, Mean Things Happening in This Land: The Life and Times of H.L. Mitchell Cofounder of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008).

Grift Stockley, Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008).

Jennifer Wallach and John Kirk, eds., Arsnick: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Arkansas (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011).

Johnny E. Williams, African American Religion and the Civil Rights Movement in Arkansas (Jackson: the University Press of Mississippi, 2003).

Nan Elizabeth Woodruff, American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press).