Dick Gregory

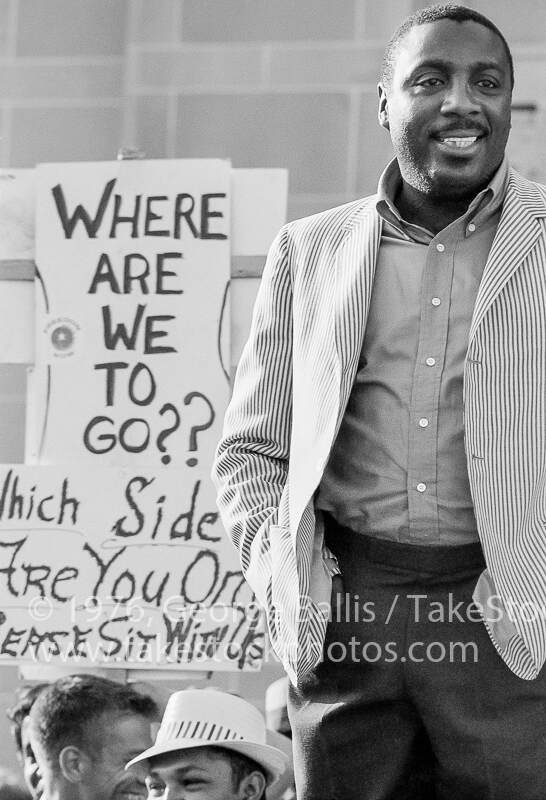

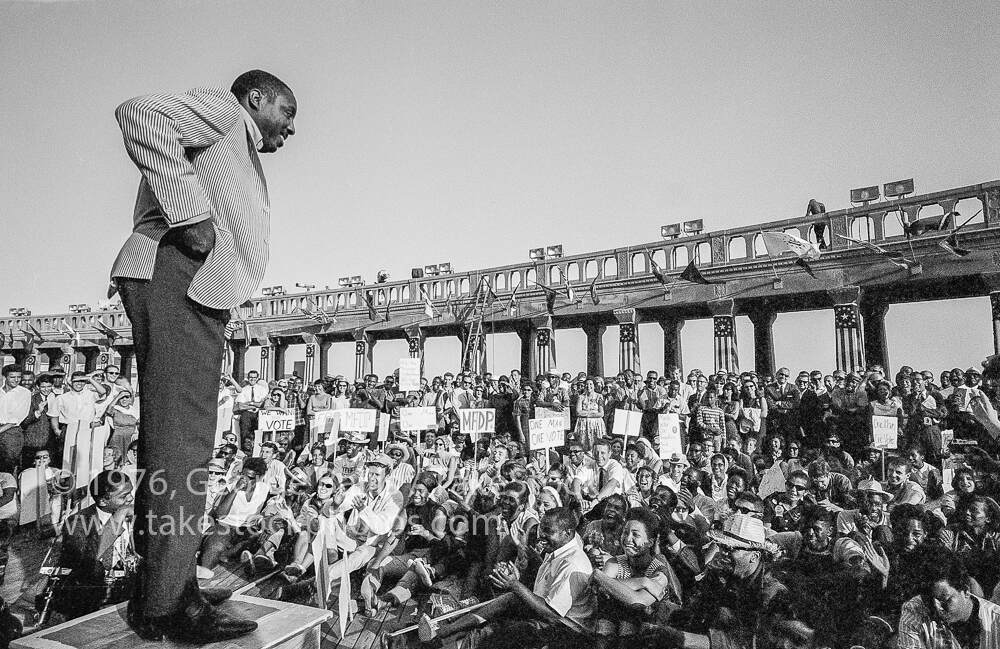

A photograph of Dick Gregory at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, 1964, George Ballis, Take Stock

October 12, 1932 – August 19, 2017

Raised in St. Louis, Missouri

In the winter of 1963, white authorities cut off commodities in Leflore and Sunflower counties where SNCC was making its biggest effort in Mississippi. The optional federal government program permitted poor counties to receive surplus government food or “commodities” for distribution to the poor. In the sharecropped cotton plantation land of the Delta, this food was vital to making it through the winter.

SNCC put out a national call for food. When Dick Gregory heard about the surplus food cut-off, he chartered a plane and sent 14,000 pounds of food to Greenwood. This was a first step that would lead the renowned comedian into increasingly deeper involvement with the Southern Civil Rights Movement. Both the surplus food cutoff and Gregory’s relief, noted Bob Moses, enabled many for the first time to see clearly “the connection between political participation and food on their table.” SNCC staff handed out food and voter registration forms.

In the spring, SNCC organizers invited Gregory to speak at a mass meeting in Greenwood. The community had never heard a Black man speak publicly in the manner that Gregory did. He made fun of the police, calling them, “a bunch of illiterate whites who couldn’t even pass the test themselves.” Gregory also called out the local preachers reluctant to involve themselves with the Movement and said, “These handkerchief heads don’t realize this area is going to break … If you have to pray in the street, it’s better than worshiping with a man who is less than a man!” The meeting erupted into laughter and applause. A week later, 31 ministers signed a statement in support of the voting rights drive.

Dick Gregory at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, 1964, George Ballis, Take Stock

Gregory did not flinch from putting himself in the path of danger. Once in a mass meeting in Clarksdale, Mississippi, a bomb was tossed through a window, and people started rushing towards the door. Gregory grabbed the microphone, and said, “Where are you going? The man who threw it is outside God’s house. The Man who’s supposed to save you lives here.” Someone picked up the bomb and threw it back outside, and the meeting continued. The Clarksdale police chief denied that his officers were responsible for the bomb, “If one of our men threw that bomb,” he said “you’d better believe it would have gone off.”

Gregory was constantly speaking to white authorities in startling, unexpected ways. During the protests in Greenwood, a police officer dragged Gregory across the street. “Thanks a million,” Gregory told him, “up north police don’t escort me across the street.” On another occasion, he wagged his finger in the faces of white policemen gathered in front of the county courthouse. “Who you calling nigger,” he told them, “You ain’t nothing but niggers yourselves. Nigger, nigger, nigger, nigger,” he continued while still wagging his finger.

Gregory continued working with SNCC throughout the sixties. He traveled with SNCC’s Freedom Singers and included jokes about the South in his act. In his memoir, Gregory wrote, “I really hadn’t planned to lead the marching [in Greenwood], but looking at those beautiful faces ready to die for freedom, I knew I couldn’t do less.”

Sources

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Dick Gregory, Nigger: An Autobiography of By Dick Gregory and Robert Lipsyte (New York: A Washington Square Press Publication, 1964).

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Howard Zinn, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 1964).