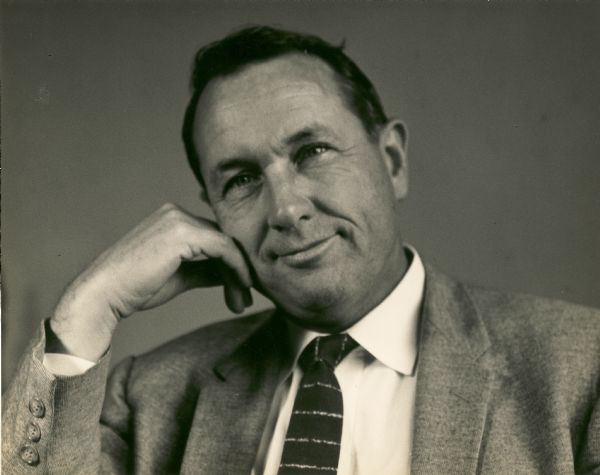

Myles Horton

July 9, 1905 – January 19, 1990

Raised in Savannah, Tennessee

When SNCC began its with relationship Myles Horton in 1961, they drew on someone with decades of experience in training activists. As founder and director of the Highlander Folk School (today known as the Highlander Center for Research and Education), Horton trained activists of both the Labor Movement and the Civil Rights Movement. SNCC had its earliest voter registration training sessions at Highlander.

Born in 1905 in the Appalachian community of Savannah, Tennessee, Horton’s family was poor but socially active. The family, and through them Myles Horton, shared a deep antipathy toward exploitation with many people in Applachia: “My first feeling about the wage system was that it was very unjust for somebody to have to work so hard and get so little, and for somebody else to have so much.”

Horton left home at 15 to get a high school education while also working as a laborer. After high school, he completed undergraduate studies at Cumberland University. He also taught as a Vacation Bible School teacher with the Presbyterian Church. At one point in class, he asked the participating rural workers what their lives were like, and he listened to them intently. This reflected an approach to education that was a guiding principle throughout his life: education wasn’t exclusively about giving information to people but also about discovering a perspective with them. This would greatly influence SNCC’s approach to organizing.

That kind of principle had inspired Horton to establish the Highlander Folk School in the fall of 1932. Having investigated the folk high schools for rural workers while in Denmark in 1920, Horton sought help among his network of mentors in the United States to start a similar program in the foothills of Tennessee. It was not welcomed by the state. After decades of hostility including intense red-baiting, the state of Tennessee finally revoked Highlander’s license in 1961 and seized its property in Monteagle.

Nonetheless, reopening Highlander in Knoxville as a research and educational center, Horton continued his efforts at providing a critical training base for activists. He sought out activists already agitating for desegregation and other civil rights. For SNCC’s Bob Moses, Curtis Hayes, Sam Block, and Hollis Watkins, who arrived for training in 1962, Highlander was a critical beginning in registering Mississippi’s voters. Horton also helped COFO organize Freedom Schools in Mississippi.

Horton was radical in his concern for the poor and that concern led him directly into involvement with the Civil Rights Movement. Even before SNCC activists began their relationship, Martin Luther King, Septima Clark and Rosa Parks had established relationships and involvement with Horton and Highlander.

Myles Horton (second from the left) at a Highlander meeting, August 31, 1957, Nashville Public Library Digital Collections

At the end of one training workshop session, Horton reminded the SNCC activists to find the balance between challenge and respect. A Delta farmer had concrete fears behind his reluctance to vote, but Horton encouraged SNCC field secretaries to respect that fear and then challenge him. Another workshop attendee counseled them to “go to their homes, eat with them, talk the language they talk…then go into your talk about the vote.”

The thing about Highlander was that the real answers never came from Highlander but from the activists themselves who went there. At the end of their training session under Horton, the SNCC activists devised their own plans for entering into and mobilizing communities in the Magnolia State. The style and success of the organizing was their own, but it didn’t come from out of nowhere. It was informed by their encounter with organizing methods like Horton’s. Without such methods, communities would have been led by SNCC, instead of leading the way themselves.

Sources

Myles Horton with Judith Kohl and Herbert Kohl, The Long Haul: An Autobiography (New York: Teachers College Press, 1998).

Myles Horton, The Myles Horton Reader: Education for Social Change, edited by Dale Jacobs (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2003).

Aimee Isgrig Horton, The Highlander Folk School: A History of its Major Programs, 1932-1961 (New York: Carlson Publishing Inc., 1971).

Aldon Morris, The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Social Change (New York: The Free Press, 1984).