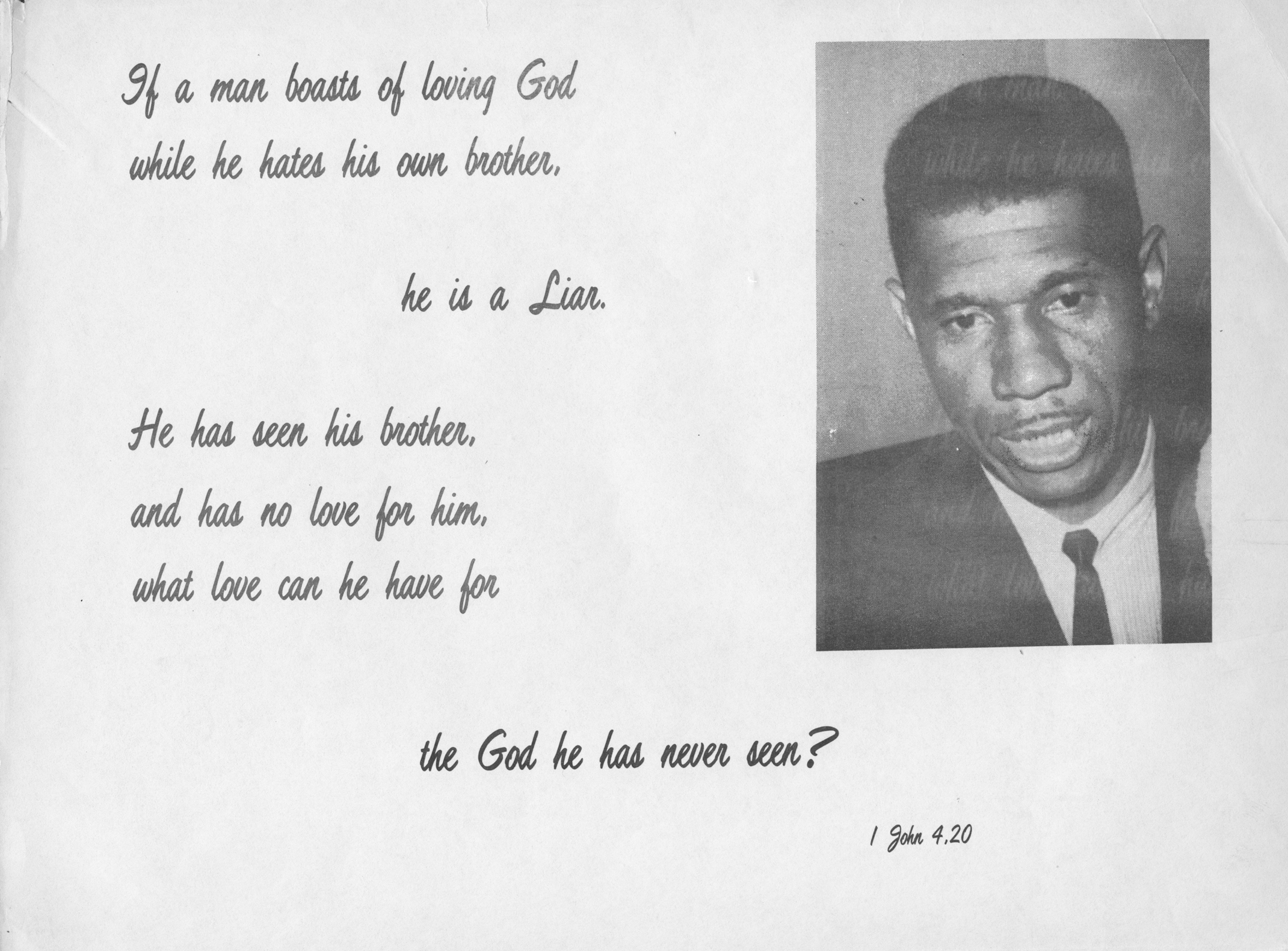

June 12, 1963

Medgar Evers murdered

Medgar Evers made his total commitment to the Mississippi Movement clear. “As you can see, I do not plan to leave,” he said in Jackson in 1956. And he always understood that his life was in danger. “I am anchoring myself here for better or for worse (I hope better), but if worse comes I’ll be in the middle of it.”

Evers’ had long mentored young people in the state. They included some of SNCC’s most influential leaders, such as Dorie and Joyce Ladner who met Evers as teenagers when he set up an NAACP youth chapter in their hometown of Hattiesburg.

As SNCC expanded voter registration into the Delta, violence against movement workers also increased. Medgar Evers was Mississippi’s first NAACP field secretary, and he was used to the threat of violence. White Citizens’ Councils and local police across the South terrorized Blacks fighting for power–especially those as well known as Medgar Evers. The day after the sit-ins at Woolworth’s in Jackson, someone dropped a firebomb on Evers’ carport while he was at a mass meeting; his wife Myrlie put out the fire with a garden hose.

When Evers left home on June 12, 1963 for a NAACP meeting, he told his beloved wife, “Myrlie, I’m so tired, I don’t think I can go on, but I can’t stop.” Working amidst the violence was taking its toll on him and on other organizers, even as they persevered.

Exhausted after a reportedly disappointing and drawn-out meeting that night, Evers came home around midnight where Myrlie and their children were waiting up for him. Arms full of NAACP T-shirts, he got out of his car and shut the door. “In that same instance, we heard the loud gun fire,” Myrlie recounted. Medgar Evers was shot in the back by a sniper hiding 150 feet away in a honeysuckle thicket. Byron De La Beckwith fired a single bullet, dropped the rifle, and ran. Evers stumbled inside and collapsed. Only 38-years-old, he died on the way to the hospital from internal injuries and blood loss.

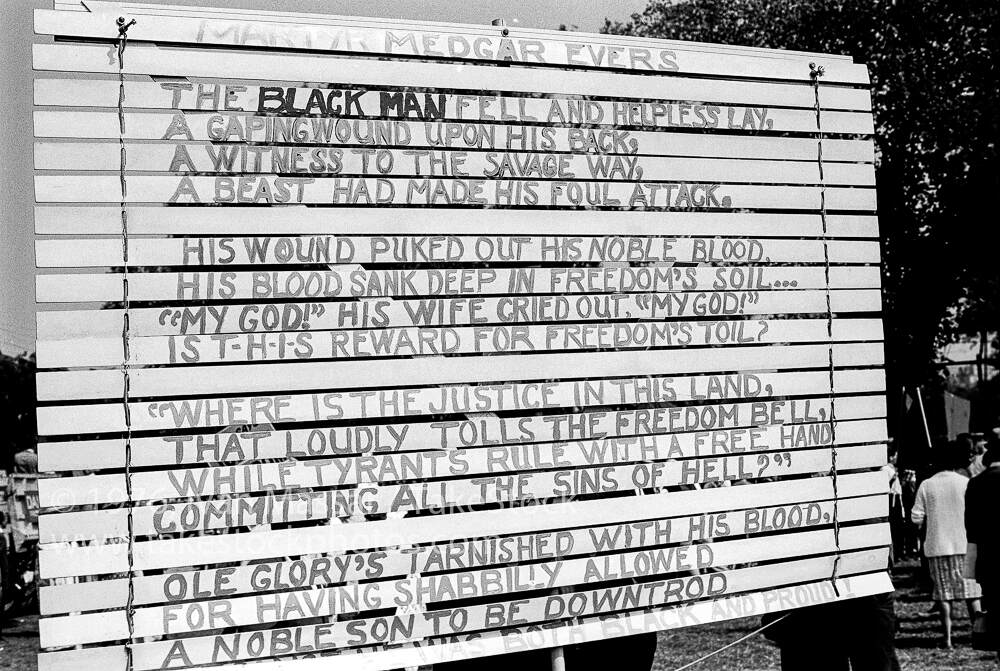

The tragic news spread across the country to movement centers, and thousands responded in fury and anguish. The next day, Doris Ladner went to the Masonic temple where NAACP meetings were usually held and saw two white police officers sitting on motorcycles. “I ran up to them and started screaming, ‘Where were you last night? Why are you here now? Shoot! Shoot! Shoot us in the back like you did Medgar Evers…’ just screaming, just enraged, enraged. The amount of rage I can’t even begin to describe.” Ministers, students, and local people took to the streets that day, continuing to demand change in Mississippi.

On June 16th, 4,000 people mourned at Evers’s funeral at the Masonic Temple, and 5,000 more joined the procession to Collins Funeral Home. The mayor made a public mandate against singing at the march, but neither he nor his police force could stifle the songs of rage and sorrow that came from the marchers that day. As music rose from the mourning crowd, police tried to stop them with dogs and clubs, and the marchers fought back.

The evidence against Byron De La Beckwith was incontestable. His fingerprints matched the rifle lying outside the house, and he had publicly sworn to “make every effort to rid the U.S. of the integrationists.” But long-instilled racism resulted in a “not guilty” verdict by the all-white jury in February 1964, despite the unprecedented urging of the district attorney for a guilty verdict. If De La Beckwith had been found guilty, he would have been the first white man put to death for murdering a Black person. Even after two mistrials and a hung jury, the killer spent only 10 months in jail and was released on a $10,000 bail.

Finally, in 1994, based on new evidence, De La Beckwith was prosecuted by the state. He was convicted of murder on February 5, 1994. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Sources

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Michael Vinson Williams, Medgar Evers, Mississippi Martyr (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011).

Interview with Dorie Ann Ladner and Dr. Joyce Ladner by Joseph Mosnier, September 20, 2011. Civil Rights History Project, Library of Congress.