Jean Wheeler

April 9, 1942 –

Raised in Detroit, Michigan

“I did anything I was big enough to do.” That was how Jean Wheeler summed up her work in SNCC. She had joined the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), Howard University’s SNCC-affiliate, as a student in 1960. Less than two years later, Stokely Carmichael, a fellow student and NAG-member, met her on the lawn outside Howard’s library and handed her a bus ticket to Atlanta to join SNCC’s southern work. “So I got my ticket, I left, and then my life was changed forever.”

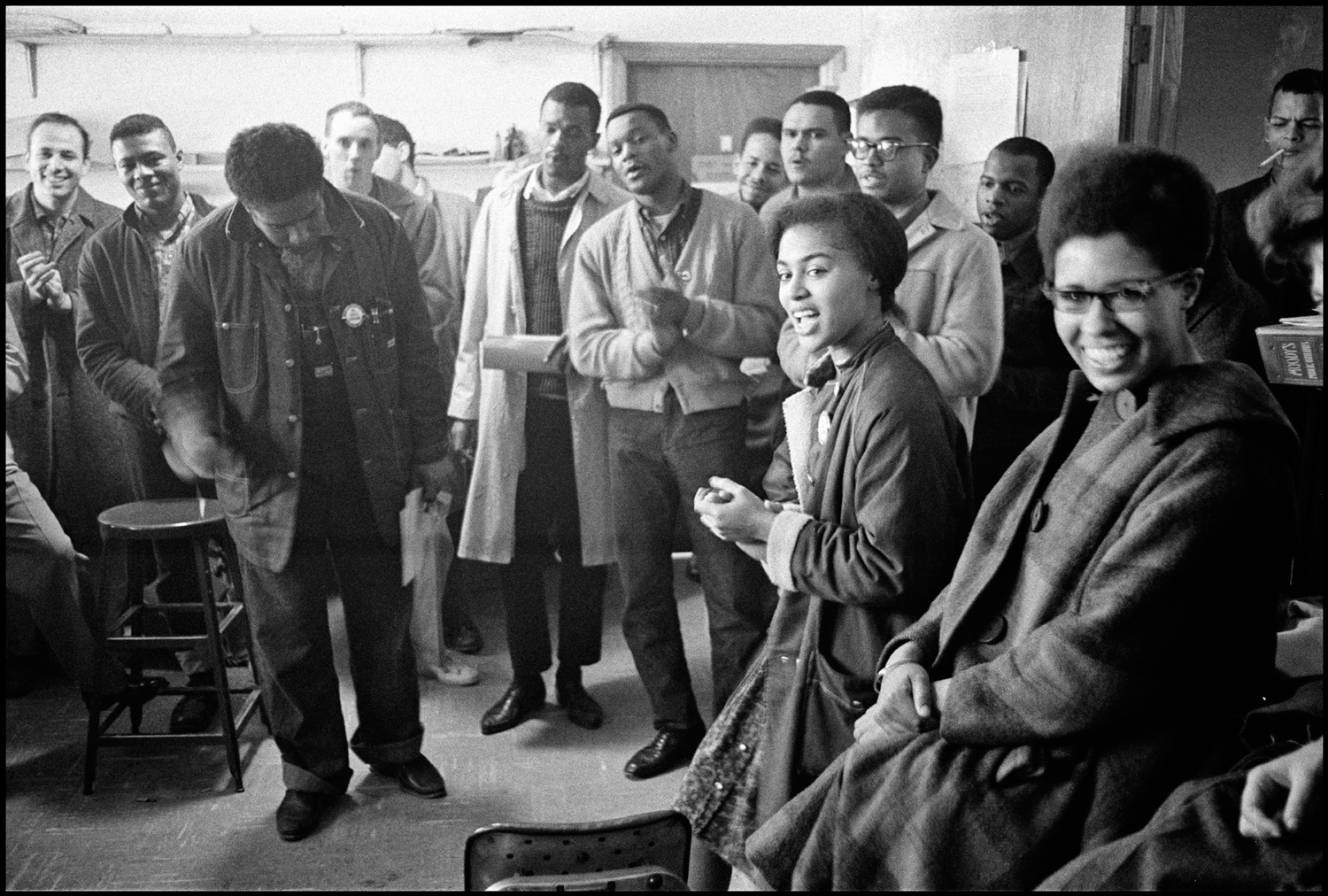

James Forman leads singing in the SNCC office on Raymond Street in Atlanta, (from left) Mike Sayer, MacArthur Cotton, Forman, Marion Barry, Lester McKinney, Mike Thelwell, Lawrence Guyot, Judy Richardson, John Lewis, Jean Wheeler, and Julian Bond, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 123, Bleakbeauty.com

Wheeler worked with Southwest Georgia project in 1963 before joining SNCC’s efforts in Mississippi in 1964.

Figuring out what she was big enough to do was not without uncertainty. In 1964, when she was left alone at a voter registration meeting in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Wheeler waited for an absent coworker, hoping that he would start the meeting. But as people began to set up chairs, file into the Masonic Hall, and pass fans down the aisle to keep cool from the humid summer air, Wheeler realized that she had to take charge. She got up on stage and spoke about why they were gathered: to show that Black Mississippians could enroll in a political party parallel to the Democratic Party that had excluded them. Organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was a pivotal experience for SNCC, but this specific meeting was also a huge moment for Jean Wheeler. “I had helped the Mississippi challenge to become an important part of history…It was the day I became an organizer in my bones.”

Before Freedom Summer, she had traveled Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio for the orientation of volunteers. When the packed audience learned that the CORE workers, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, and volunteer, Andrew Goodman, were missing and feared dead, the entire auditorium grew completely silent, almost cold. Jean Wheeler decided to get up and sing.

Jean Wheeler Smith and Jack Minnis at SNCC conference in Waveland, MS, November 1964, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, 163, Bleakbeauty.com

“I don’t know why

I have to cry sometimes.

…

It would be a perfect day,

but there’s trouble all in my way.

I don’t why,

but I’ll know bye and bye.”

By the time she made it to the front of the auditorium the rest of the people joined her. With renewed resolve, the volunteers continued orientation and prepared for the massive summer campaign.

After the orientation, Wheeler went with ten to twelve other organizers right to Philadelphia, Mississippi, where Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner had gone missing. There she helped set up a search party and later established a Freedom School. While in Philadelphia, she led with respect for the community, even sleeping alone in a two-room house, away from the male organizers in the freedom house. Even though she was terrified each night, wedging a chair to the door to secure it, she fought through her fear and did her work as an organizer.

Like most activists in SNCC, Wheeler believed that what made SNCC work was its emphasis on the leadership of everyday people. Years later she explained that “we were creating a trusting and loving atmosphere and a supportive atmosphere…We let the person we were trying to organize, lead. We let him express what was important to him and then we followed.”

Wheeler worked with SNCC into 1967 and then went on to become a child and adolescent psychiatrist working with community-oriented mental health programs.

Sources

Cheryl Greenburg, ed., A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

Wesley Hogan, Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC’s Dream for a New America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

Jean Smith Young, “Do Whatever You Are Big Enough to Do,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 240-250.