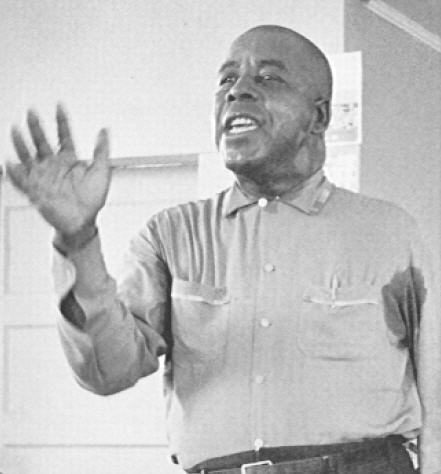

Hartman Turnbow

March 20, 1905 – August 15, 1988

Raised in Holmes County, Mississippi

On the afternoon of April 9, 1963, fourteen people arrived at the Holmes County, Mississippi courthouse in Lexington to try to register to vote. Word of their intention had gotten out, and a white posse was milling about. The county sheriff confronted the group and demanded to know, “Who’s gonna be first?” Hartman Turnbow stepped forward: “Me, Hartman Turnbow. I came here to die to vote. I’m the first.”

Although none of the “First Fourteen,” as they were called, were able to register, their actions catalyzed the Movement in Holmes. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party branch formed in the county would be one of the strongest in the state. It still exists today.

Turnbow, along with other farmers, had been attending movement mass meetings in neighboring Leflore County. One of them, NAACP leader, Ozell Mitchell, invited SNCC to organize in Holmes County. Many Blacks in Holmes County owned their own land because a New Deal Farm Security Administration program, and land ownership gave them a sense of independence that fostered their participation in the Movement. Turnbow was among the Black landowners.

After Turnbow tried to register, he noticed that “they had a write up in the Lexington Herald that ‘Hartman Turnbow was an integration leader.’ […] about 2 weeks or a little after that my house was firebombed and shot in all at the same time.” Turnbow shot back at the night riders with his .22 rifle, and it was rumored that he may have killed one of them. Turnbow believed that he had a right to defend himself and his family, explaining, “I had a wife and I had a daughter and I loved my wife just like the white man loves his’n and a white man will die for his’n and I say I’ll die for mine.”

The violence scared Turnbow but didn’t deter his activism. After his home was firebombed, he declared, “The Negro ain’t gonna stand fo’ all that beating and lynching and bombing and stuff. They found out when they tried to stop us from redishing [registering] that every time they bombed or shot or beat or cut credit …it just made him angry and more determined to keep on…and get redished.”

Turnbow was known to give powerful speeches which included turns of phrase that fellow organizers affectionately called Turnbowisms. He once called SNCC, “the student violent non-coordinated committee.”

In 1964, Turnbow joined the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. He testified about his experience with voter suppression and was an MFDP delegate at the Democratic National Convention. In Atlantic City, SNCC’s Joyce Ladner accompanied Turnbow and his wife, “Sweets,” to lobby the delegation from Oregon. “Mr. and Mrs. Turnbow held their own,” she remembered, “Mrs. Turnbow always carried a little brown paper bag. She had a pistol in it. […] But she didn’t trust those people. I mean people had tried to firebomb her home, so she might have been in the presence of a senator and a congresswoman, but she carried a gun.”

Hartman Turnbow remained grateful to SNCC’s work in Holmes, and once said, “I knew we had the right to go redish, but didn’t nobody ever stir it up,” he said. “So [SNCC organizer] John Ball he come in here … that just kicked it off.”

Sources

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Sue Lorenzi Sojourner with Cheryl Reitan, The Thunder of Freedom: Black Leadership and the Transformation of 1960s Mississippi (Lexington: University of Kentucky, 2013).