1945

Black veterans return from World War II

In many ways returned Black World War II veterans changed the climate of the South by taking up the deliberate and concerted work of dismantling white supremacy. On July 2, 1946, for example, twenty-one-year-old Medgar Evers, his brother Charles, and four other Black World War II veterans, went to the courthouse in Decatur, Mississippi to vote. They had been the first Black people there to attempt to register to vote since Reconstruction. The six veterans had returned home after fighting for democracy in France and England to find that they were still only second-class citizens.

When they arrived at the courthouse that election day, fifteen to twenty armed white men were waiting for them. So, Evers and his comrades went home to get their guns. The mob was still waiting when they returned to the courthouse, and the six veterans decided not to fight or vote that day. But that wasn’t the end. Both Medgar and his brother would go on to become important leaders in Mississippi’s Freedom Movement, Medgar especially, providing crucial support to SNCC and CORE.

While the United States denounced Hitler’s ideas of Aryan “supremacy” in Europe, U.S. hypocrisy was exposed to Black servicemen and Black civilians alike because Black people remained second-class citizens in the military and at home. Across the country, Black Americans adopted the “Double V” campaign, demanding victory abroad against fascism and victory at home over white supremacy.

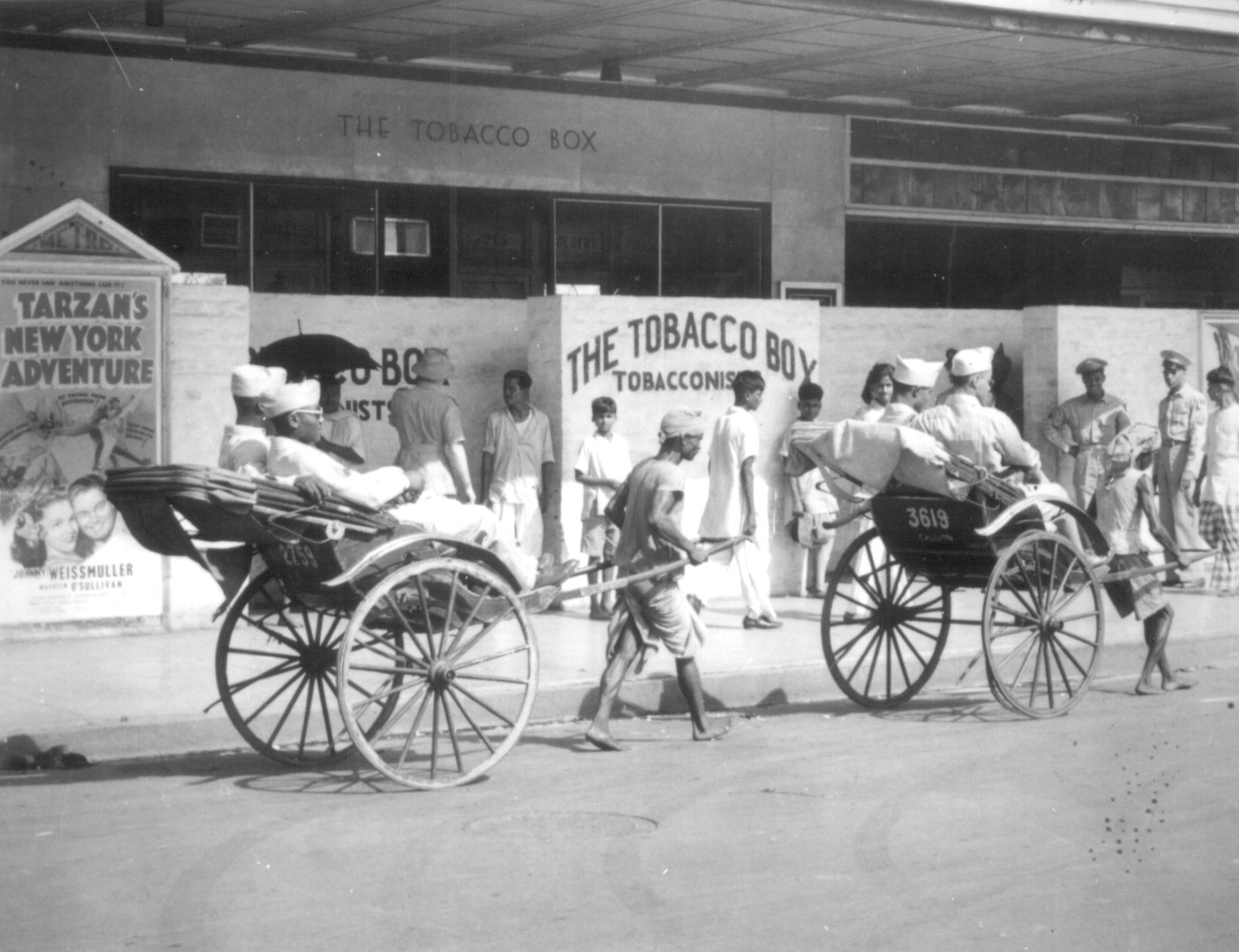

Amzie Moore was working in Cleveland, Mississippi post office when he was drafted in 1942. In Mississippi he’d had so little contact with whites he did not even know what segregation was. “I really didn’t know what segregation was like before I went into the Army,” he reflected later. After training at segregated bases across the South, he arrived in Calcutta only to find that the enlisted-men’s clubs were segregated there too. Worse, his job was to counter Japanese radio broadcasts reminding Black soldiers that they had no freedom and wouldn’t after the war either. “Why were we fighting? Why were we there?” Moore wondered.

But even a segregated military equipped Black soldiers with skills and exposed them to a wider world, and when Black soldiers returned home, they applied the new experiences gained through military service to challenging Jim Crow. “But most of all [the Army] taught us to use arms,” noted Robert Williams, a soldier who went on to lead the NAACP in Monroe, North Carolina. Black soldiers, like Williams and Medgar Evers, returned home comfortable with guns and willing to use them to protect their own.

Armed Black men were already one of the greatest fears of white southerners, and the boldness of returning veterans–demanding the vote, using the G.I. bill for higher education, and making demands on the federal government–caused even more alarm. Violence against Black people, and veterans in particular, soared after the war. Just three weeks after V-J Day, the Ku Klux Klan lit a three-hundred foot cross on Stone Mountain in Georgia. Black churches in Taylor County, Georgia, found statements hanging on their doors, reading “The first Negro to vote will never vote again.”

But such threats did not deter Black veterans in their efforts to take down white supremacy. Even before he returned home from the war, Amzie Moore joined the NAACP. At the service station he operated, he refused to hang “white” and “colored” signs on the restrooms. “God had put him on a ship and sent him around the world so that he could see that people were pretty much the same all over,” he explained.

Amzie Moore was elected president of the local NAACP and it grew into the second largest branch in the state. Helping him in this work was Medgar Evers, who had become the state field secretary of the NAACP in 1954. Evers, Moore, and NAACP leaders across the state–many of whom were war veterans–organized voter registration efforts and built networks across the state during the 1940s and 1950s.

In the summer of 1960, the first year of SNCC’s existence, Ella Baker sent Bob Moses to Mississippi to meet Amzie Moore. She had helped organize NAACP branches in the Deep South during the 1950s and knew the long war Black veterans had been waging against white supremacy. When SNCC began voter registration work in the Deep South, Black veterans made up an essential part of the older generation of activists who took the young organizers in and showed them the way.

Sources

Charles E. Cobb, Jr, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed, How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Timothy Tyson, Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

Interview with Amzie Moore by Michael Garvey, March 29 & April 13, 1977, Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi.