May 1964

Demonstrators tear-gassed at George Wallace protest in Cambridge

In 1964 the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC) was strengthening, and Cambridge was at a standstill after the powerful, right-wing Dorchester County Business and Citizens Association (DBCA) passed a referendum allowing private businesses to refuse service to its Black residents. CNAC leader Gloria Richardson warned that the Civil Rights Movement that had been built around the philosophy of nonviolence “could turn into a civil war,” because Black people wanted “freedom-—all of it here and now!”

In May 1964, as the DBCA invited Alabama governor and segregationist George Wallace, then seeking the White House, to speak about his campaign for the presidency at the Rescue and Fire Company’s Arena. As the news of this invitation spread, an uproar in Cambridge ensued. DBCA president William Wise appeared in newspapers claiming that he and the DBCA were not in fact anti-Black; instead they supported Governor Wallace because he believed building a better Cambridge centered on private enterprise instead of government funds.

On May 11, 1964, Governor Wallace stood before more than a thousand of Cambridge’s white residents telling them, “I have spoken all the way from New Hampshire to Alabama. I believe there are in this country hundreds of thousands who say stand firm and keep working.” Although his usual blatantly racist rhetoric was absent from his speech, Wallace denounced pending civil rights legislation. With each attack, the white crowd screamed, “We’ll win! We’ll win!”

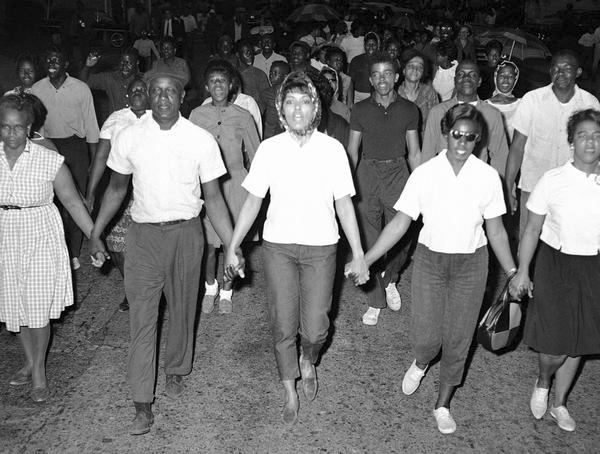

CNAC had been militantly opposed to Governor Wallace speaking in Cambridge. Just before his arrival, local youth began protesting the segregated swimming pool at the RFC Arena. The city of Cambridge had prohibited protests, citing martial law, but Gloria Richardson would not let the threat of being arrested stop her and the Black residents. She called for help from SNCC and members of the organization’s NAG affiliate, including Stokely Carmichael, Cleveland Sellers, and H. Rap Brown came to support her efforts. Richardson led a group of four hundred Black and white civil rights activists, hoping to somehow get the white supporters into Wallace’s rally. But CNAC did not anticipate what would be waiting for them.

When Cambridge got word of the planned protest, Maryland’s governor called in the National Guard. Armed with rifles with attached bayonets, the Guard met CNAC on Race Street, the street that was the geographic dividing line between Cambridge’s Black and white communities. Though the CNAC protesters were surrounded by tanks and guardsmen, Richardson climbed onto a tank and refused to get off it. The National Guard quickly arrested her.

Richardson thought she heard gunshots while being arrested, but what she heard was actually CN2, a military grade gas that had never been used on civilians before. The gas made protesters and non-protesting Cambridge residents sick, even those who lived blocks away from the protest. Carmichael had to be rushed to the hospital, and an elderly man and infant died. This, however, was just the start of the National Guard’s use of tear gas on local Black residents.

Even though George Wallace went on to secure 44.5% of Maryland’s vote in the primary, the protest was not without its own achievements within CNAC. After the heinous gassing, Gloria Richardson’s reputation as an important leader in the Movement was cemented, particularly with Cambridge’s youth.

Sources

Gloria Richardson Dandridge, “The Energy of the People Passing through Me,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 273-297.

Peter B. Levy, Civil War on Race Street: The Civil Rights Movement in Cambridge, Maryland (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003).

Gloria Richardson, “Focus on Cambridge,” Freedomways, 1st Quarter, 1964, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website, Tougaloo College.