Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was best known for mobilizing large, nonviolent protests in places like Birmingham and Selma, aimed at moving the national conscience and pushing the federal government to support civil rights initiatives. Rev. King’s charisma was crucial to this effort, which created confrontation between nonviolent protesters and local law enforcement but also aimed to stir up public outcry against blatant and often violent racial discrimination.

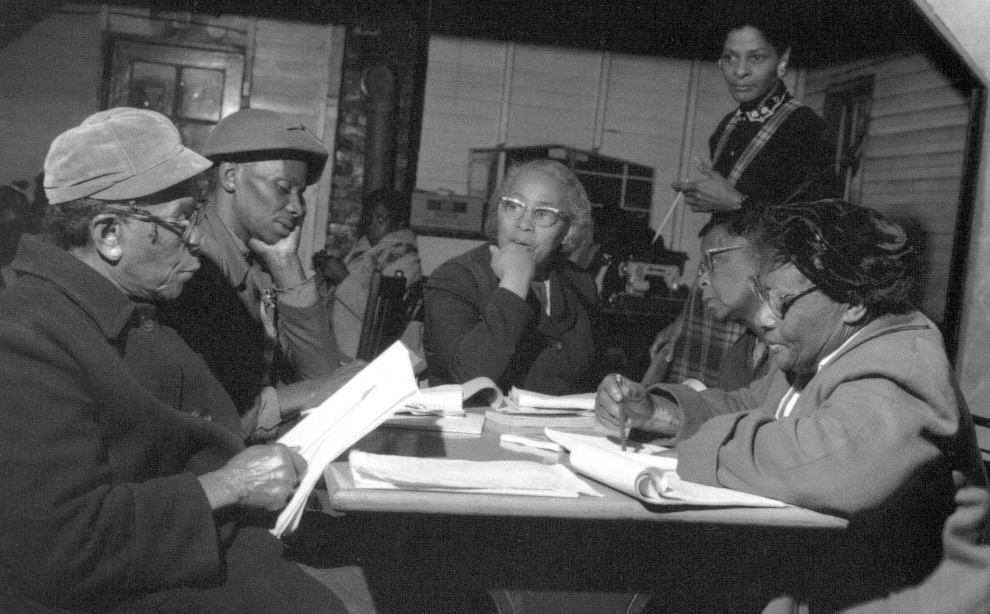

Septima Clark teaches a citizenship class in the South Carolina Sea Islands. Standing in the background is Citizenship School teacher, Bernice Robinson, crmvet.org

But another less well-known component of SCLC engaged in voter education work in the form of the Citizenship Education Program (CEP). The idea for a citizenship education program for potential Black voters was born during a 1954 workshop at the Highlander Folk School in the Appalachian Mountains of Tennessee. Septima Clark, a Charleston school teacher who had been fired from her job because of her NAACP activities, was leading the workshop. One of the attendees was Esau Jenkins, a Black farmer, businessman and former student of Septima Clark from the majority-Black John’s Island off the coast of Charleston. He said he wanted to create a school to teach literacy to Black residents of John’s Island, most of whom were unable to vote because they were illiterate or could barely read and write.

Highlander loaned Jenkins $1,500 to set up the school. By 1961, there were citizenship schools operated by seven different organizations in 21 counties in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and South Carolina. These citizenship schools became the roots of the Citizenship Education Program, which SCLC took over in 1961.

Unlike massive direct action protests, CEP classes became important spaces for grassroots organizing, as both teachers and students were drawn from local populations. In Mississippi, this work was important to SNCC’s work, and SNCC and COFO workers helped bring participants to CEP schools. In the relatively protected spaces of classrooms located in the Black community, students and teachers discussed ways in which they could effect change and address locally-defined problems. Through these classes, students learned more than literacy; they began to craft their own understandings of first-class citizenship.

CEP had a strong presence in the Mississippi Delta during the early sixties and worked hand-in-hand with SNCC’s voter registration organizing in the area. In 1961 and 1962, local Mississippians organized six citizenship schools in the Clarksdale area. CEP continued to expand in the Delta as James Bevel, a former SNCC field secretary turned SCLC staff member, and his wife Diane Nash worked to recruit teachers.

Citizenship schools provided an essential educational component for the emerging voter registration campaign in the Delta. They transcended organizational affiliations with NAACP members working closely with field secretaries from SNCC, CORE, and SCLC. Citizenship schools existed in every major area of movement activity, typically taught by local women who could use their established reputations, economic resources, and considerable community contacts to support local movement activity. CEP provided a vehicle for local women of varying backgrounds to become leaders within the Mississippi Movement, in charge of instilling within local people the confidence to attempt to register to vote. Citizenship schools became important politicization centers for community adults, as well as institutionalized grassroots leadership development.

Sources

Katherine Mellen Charron, Freedom's Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

Deanna Gillespie, “‘First-Class’ Citizenship Education in the Mississippi Delta, 1961-1965,” Journal of Southern History (2014), 109-142.

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).