James Bevel

October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008

Raised in Itta Bena, Mississippi

As Charlie Cobb remembered, “there was nobody like James Bevel. He was crazy and brilliant, all the same time.” James Bevel was one of seventeen children born to a sharecropping family in Itta Bena, Mississippi. He grew up working on a cotton plantation, all the time wondering “what can I possibly do to make a difference in ending segregation?”

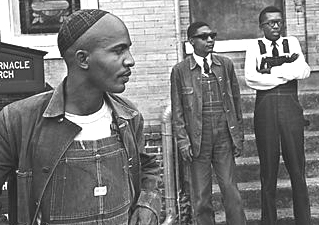

James Bevel (far left) outside the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Selma, Alabama, Birmingham News, crmvet.org

While studying at the American Baptist Theological Seminary, James Bevel became one of the leaders of the Nashville Student Movement. Bevel, along with fellow Nashville students John Lewis, Diane Nash, Marion Barry, and Bernard Lafayette, were trained by Reverend James Lawson in Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent direct action. These students from the Nashville Student Movement deeply influenced SNCC in its early days, and many would become prominent in SNCC and SCLC.

Bevel was part of the small SNCC contingent, all veterans of the Nashville sit-ins, who helped form the Jackson, Mississippi Nonviolent Movement and establish the first Freedom House in a Black neighborhood on Rose Street. This Movement produced a core of young workers who would campaign for voting rights in the Delta.

In 1962, Bevel began working full-time for SCLC’s Citizenship Education Program in the Mississippi Delta. This program emerged in 1954 at a workshop led by Septima Clark at the Highlander Folk School in the Appalachian Mountains of Tennessee and was an important component of the growing voter registration campaign in Mississippi.

Bevel worked closely with SNCC and was a powerful, mobilizing preacher. Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer said that hearing Bevel preach one night, connecting religious faith to political action, finally persuaded her to join seventeen others from Sunflower County and go to the county courthouse in Indianola to attempt to register to vote four days later. Bevel spoke at mass meetings across the South, inspiring many local citizens to find their voice within the Movement.

James Bevel (center) at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s wake, April 9, 1968, Jim Peppler Southern Courier Photograph Collection, ADAH

In 1963, Bevel took on a new role as the SCLC’s director of Direct Action and Non-violent Education. In Birmingham when Dr. Martin Luther King was jailed, Bevel organized what became known as the Children’s Crusade and faced Police Commissioner Bull Connor’s fire hoses and police dogs. He helped plan the 1963 March on Washington and the Selma-to-Montgomery marches in 1965. When King was shot at the Lorraine Motel in 1968, Bevel was at his side.

Reflecting on his experiences, Bevel once noted, “I was of the impression that the Movement was an act of God in history and that I was simply one of the persons that he had called forth to be involved in it…. Here was a people who had been oppressed and that they were going to change that condition.”

Sources

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Charles Payne, I’ve Got Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).