Bettie Mae Fikes

April 16, 1946 –

Raised in Selma, Alabama

Known as “the Voice of Selma,” Bettie Mae Fikes’ powerful singing voice inspired Blacks in Selma to fight for equality. Fikes was born into family of gospel singers and preachers. By the time she was four, she had sung her first church solo and started traveling and singing with her parents’ groups, the SB Gospel Singers and the Pilgrim Four. Her mother died when Fikes was 10-years-old, and from then on, she was shuffled between Selma, Detroit, and California to live with family.

Teenagers singing at the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Selma, Alabama, 1963, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, 103, dektol.wordpress.com

Although she had been taught to never work in the homes of white people or go where she wasn’t wanted, Fikes never fully understood the problem. “I could tell there was something wrong. I just didn’t know what,” she remembered. It wasn’t until she came back to Selma that she began to understand how white supremacy worked.

Bettie Mae Fikes joined SNCC at sixteen, mainly as “an avenue to get out of the house and to keep from going to church so much.” Her classmates from R.B. Hudson High School, Charles Bonner and Cleophus Hobbs, had gotten hooked up with SNCC’s Bernard Lafayette and his wife, Colia Liddell Lafayette, who directed SNCC’s Selma project, “and they got all of their friends that they knew involved.” Fikes met with Bernard Lafayette and Worth Long and began helping them pass out leaflets to recruit adults for voter registration. After moving around so much as a child, the Movement became Fikes’ family. SNCC activists Long and Tom Brown were like older brothers, and Movement people even attended her high school graduation. With this new family, Fikes sat in at lunch-counters, boycotted buses, registered voters, and led walkouts of R.B. Hudson High School for desegregation.

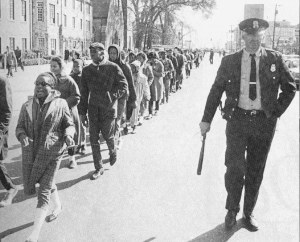

High school students arrested for marching in support for voter registration in Selma, Alabama, 1963, crmvet.org

Fikes often led marches in song. She would change the lyrics of gospel songs for the Movement. So hymns like “This Little Light of Mine” were changed to “Tell [Sheriff] Jim Clark, I’m going to let it shine.”

Like many young movement participants, she sometimes found she had to defy more cautious adults in her family and community. One day in 1963, she was instructed to pay her aunt’s water bill and told not to stop at the local church where a mass meeting was taking place. But she went to the church anyway and was immediately swept up into leading a protest to city hall. Local police threatened the students will cattle prods, but Fikes got to her knees and made them carry her off to jail. Fikes went from the local jail to Camp Selma and Camp Camden, state prison camps in Dallas and Wilcox Counties. Over her three weeks in jail, Fikes recruited other teenagers into the Movement.

Fikes participated in Bloody Sunday, giving updates back and forth from Brown Chapel to the head of the line. Later on, she joined the Freedom Singers with Matthew Jones, Cordell Reagon, and Emory Harris. Bettie Mae Fikes continued using her voice to empower the Black community throughout her singing career. The Movement enabled her to recognize how important music was in the freedom struggle. “I have been singing for freedom ever since,” she explained.

Sources

Bettie Mae Fikes, “Singing for Freedom,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 460-470.

Our Voices: Song & Music, featuring Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, SNCC Digital Gateway.

Interview with Charles Bonner and Bettie Mae Fikes by Bruce Hartford, 2005, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.