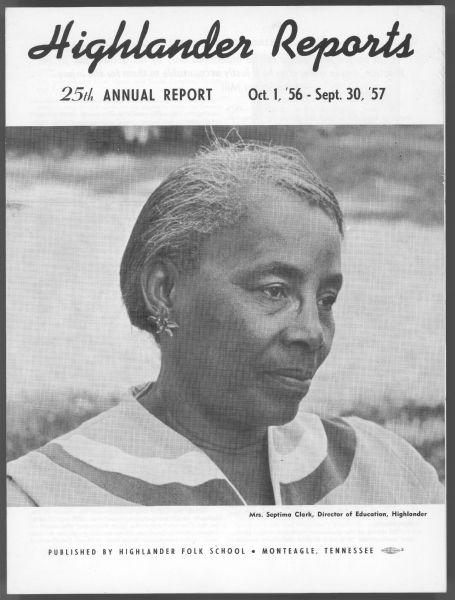

Septima Clark

Septima Clark at Highlander Folk School, undated, Highlander Research and Education Center Records, WHS

May 3, 1898 – December 15, 1987

Raised in Charleston, South Carolina

Septima Poinsette Clark pioneered the link between education and political organizing, especially political organizing aimed at gaining the right to vote. “Literacy means liberation,” she stressed knowing that education was key to gaining political, economic, and social power.

Long before SNCC’s Freedom Schools, Clark was developing a grassroots citizenship education program that used everyday materials to think about big questions. From reading catalogues to writing on dry cleaner bags instead of chalkboards, Clark not only found creative ways to teach literacy but also helped people become leaders. “Don’t ever think that everything went right. It didn’t,” she acknowledged. “Many times there were failures. But we had to mull over those failures and work until we could get them ironed out.”

Clark was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1898 to a mother who was “fiercely proud” and a father who was gentle and tolerant. Both recognized the importance of education, although they came from very different life experiences. Clark’s father was formerly enslaved on the Poinsette Plantation and would tell Clark about how, as a child, he would take his master’s children to school and wait outside while they were in class. Her mother was raised in Haiti and was taught how to read and write at a young age. When they saw the conditions of Clark’s grade school as compared to those that the white children of Charleston attended, they were enraged. And so, they sent her to a woman who taught neighborhood children in her home across the street. Clark eventually went on to attend the Avery Normal School in Charleston.

Clark decided to become a teacher herself, seeing education as a tool to be put in the hands of the people to gain a better life. By 1916, Clark had received her teaching license and got a job on Johns Island off the coast of South Carolina. Blacks were not permitted to teach in public schools in Charleston. Looking for ways to pass the time in the evening, Clark began teaching adult literacy on the island after school. She would have her students write stories about their daily lives and think critically about the world around them.

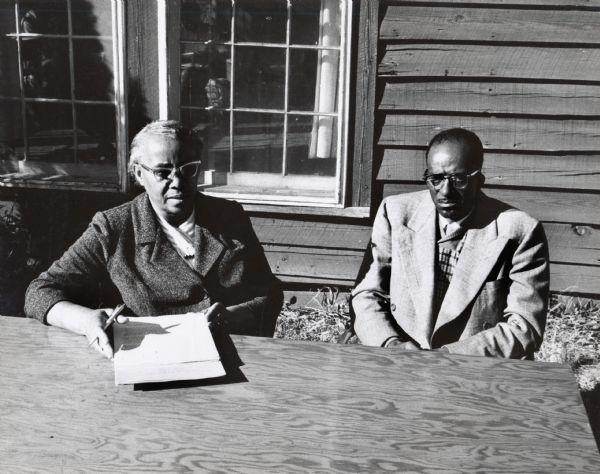

Photograph of workshop participants at Highlander Folk School, Monteagle, Tennessee, August 31, 1957, John Malone, Nashville Public Library

A few years later, Clark had a conversation with someone about the NAACP and joined, spurring her to move back to Charleston and take part in a successful campaign to change the policy that prevented Black teachers from working in public schools. For a time after, she lived in Columbia, South Carolina, and worked at Booker T. Washington High School before returning to her hometown to care for her mother. She began teaching there, but she lost her teaching position in 1956 because of her affiliation with the NAACP. Clark then became the director of workshops at the Highlander Folk School founded by Myles Horton, which she had first visited in 1954.

While at Highlander, Clark stayed connected to her teaching roots, developing the Citizenship School curriculum she had begun developing on Johns Island. She encouraged one of her former students, Esau Jenkins, to start coming to workshops at Highlander. Jenkins had become a respected leader on Johns Island and had even run for the school board. Although the Black community largely supported him, so few Blacks were registered to vote on Johns Island that Jenkins was defeated.

Taking what he had learned from Highlander, Jenkins decided to take matters into his own hands and began a literacy effort on the bus he used to take tobacco workers and longshoremen to Charleston. With a seed grant from Highlander, Jenkins took this “rolling school” to the back of a grocery store on the island, which hid the school from the white community’s gaze. By 1961, 37 Citizenship Schools had been established on the Sea Islands and nearby mainland. These students went on to start a low-income housing project, credit union, nursing home, and more within their communities.

The Citizenship Schools eventually became part of SCLC, and Clark moved to Atlanta, driving all over the Deep South to recruit folks to be Citizenship School teachers. After a workshop at the Dorchester Cooperative Community Center in Macintosh, Georgia, participants would go back to their communities, start discussing problems in their towns and organize their own citizenship classes.

Clark believed in the power of literacy and nonviolent resistance, and she was interested in the work of the young activists. Like her good friend Ella Baker, Septima Clark bridged the gap between SNCC and an older generation in a way that few did, and her lifelong work in adult literacy and citizenship education helped pave the way for SNCC’s organizing work, especially the Freedom Schools of Mississippi.

Sources

Katherine Charron, Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

Septima Poinsette Clark, Ready from Within: Septima Clark and the Civil Rights Movement (Lawrenceville, NJ: Africa World Press, 1990).

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).