August 8, 1965

President Johnson signs Voting Rights Act

It was a chilly spring morning on March 7, 1965, when some 600 people marched over the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama protesting the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was killed by a white highway patrolman during a nighttime demonstration for voting rights in nearby Marion, Alabama. As the marchers reached the middle of the bridge, they were met by a phalanx of state troopers backed by Sheriff Jim Clark and his posse on horseback.

When they refused to disperse, the policemen charged, throwing tear gas canisters and beating protesters with billy clubs. Sheriff Clark and his men rode through the chaos on their horses, using bullwhips and ropes and cattle prods to steer the crowd like livestock. The violence was captured on camera by the national news media and stirred national and international outrage.

The Selma campaign became the immediate catalyst for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. On March 15, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson spoke before Congress and the country, calling for the passage of a bill that eliminated the major barriers to Black voting. “We can not, we must not refuse to protect the right of every American to vote in every election that he may desire to participate in,” Johnson declared. Over the next few months, members of Congress and officials from the Johnson administration debated the specifics of the law. In the end, the bill included provisions that removed the literacy test or any type of registration exam as a qualification for voting. It also required federal voting examiners in voting districts in which less than 25% of eligible minority voters were registered.

On August 8th, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. The signing of the act was celebrated as a victory for American democracy. Dr. King congratulated the President. “I am convinced,” he wrote in a personal letter, “that you will go down in history as the president who issued the second and final Emancipation Proclamation.”

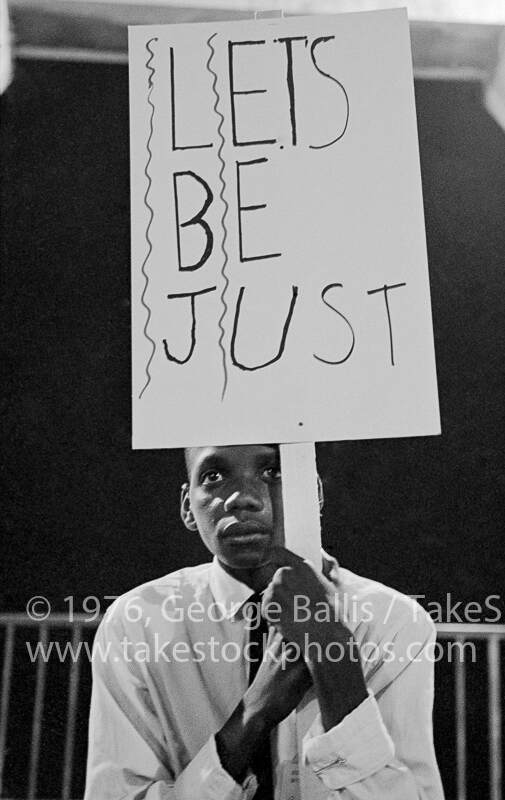

However, Black people at the grassroots had carried on the struggle for voting rights long before and after President Johnson ceremoniously signed the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Local activists and community organizers, who recognized that many of the problems facing Black people in the Deep South stemmed from political powerlessness, had been struggling to gain voting rights for decades. In the early sixties, SNCC continued efforts begun by an older generation and began organizing Black communities in the Black Belt South. The young organization’s dedication in the face of violence, as well as its ingenuity and energy, helped accelerate the fight for voting rights.

In 1963 SNCC established a voting rights project in Selma, Alabama. Working closely with local voting rights activists, especially the Boynton family, SNCC workers taught citizenship classes, organized mass meetings at local churches, and escorted people to register to vote. The project, like all of SNCC’s projects in the Deep South, encountered stiff local resistance. Sheriff Jim Clark and his posse violently kept Black people in their places, often using cattle prods and blackjacks against nonviolent protesters. The local political and economic elite formed one of the strongest white Citizens’ Council and used their influence to undermine united Black struggle.

Despite the flagrant denial of constitutional rights for Black people, the federal government offered little support to the Movement. Both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations were more concerned with their political need for support from very powerful Southern senators and congressmen or “Dixiecrats.”

In 1964 COFO workers and local activists in Mississippi organized an independent parallel political party called the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). The party challenged the racially-exclusive regular Mississippi Democratic Party for recognition at the National Convention in Atlantic City. The national party, under the directorship of Lyndon Johnson, refused to seat the MFDP–but the convention challenge, as it became known, brought the denial of Black voting rights to the doorstep of power and into the national consciousness. National politicians could no longer ignore or keep at arm’s reach the pervasive denial of African American demands to full citizenship.

President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, which was by no means a small accomplishment. However, the fight for Black voting rights wasn’t waged by President Johnson, nor did it take place in the corridors of power of the nation’s capital. It was waged by local Black people and community activists, who fought back against the repressive and often violent enforcement of Black second-class citizenship.

Sources

Stokely Carmichael with Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (New York: Scribner, 2003).

Clayborne Carson, et al., eds., The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Accounts from the Black Freedom Struggle, 1954-1990 (New York: Penguin Books, 1991).

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997).

David Garrow, Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978).

Peter Levy, ed., Documentary History of the Modern Civil Rights Movement (New York: Greenwood Press, 1992).

Robert P. Moses and Charles E. Cobb, Jr., Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001).

Fred Powledge, Free At Last? The Civil Rights Movement and the People Who Made It (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1991).

Stephen Tuck, “Making the Voting Rights Act,” The Voting Rights Act: Securing the Ballot, edited Richard M. Valley (Washington DC: CQ Press, 2006).

Emilye Crosby, “The Selma Voting Rights Struggle: 15 Key Points from Bottom-Up History and Why It Matters Today,” Teaching for Change, January 2, 2015.