October 1961

SNCC arrives in Albany

By 1961 SNCC, still practically brand new, was trying to craft its identity and find its footing following the sit-in movement. Some wanted to keep with the tradition of the sit-ins and focus the organization’s energies on nonviolent direct action. Others wanted to focus on voter registration, especially in the Black Belt, where disenfranchised Blacks made up the majority of the population. Despite intense internal debates, there was a broad consensus among activists that, in the words of James Forman, it was “important then to just do, to act, as a means of overcoming the lethargy and hopelessness of so many Black people.” Rather than establish rigid definitions of goals and tactics, “it seemed best then to experiment and learn and experiment some more.”

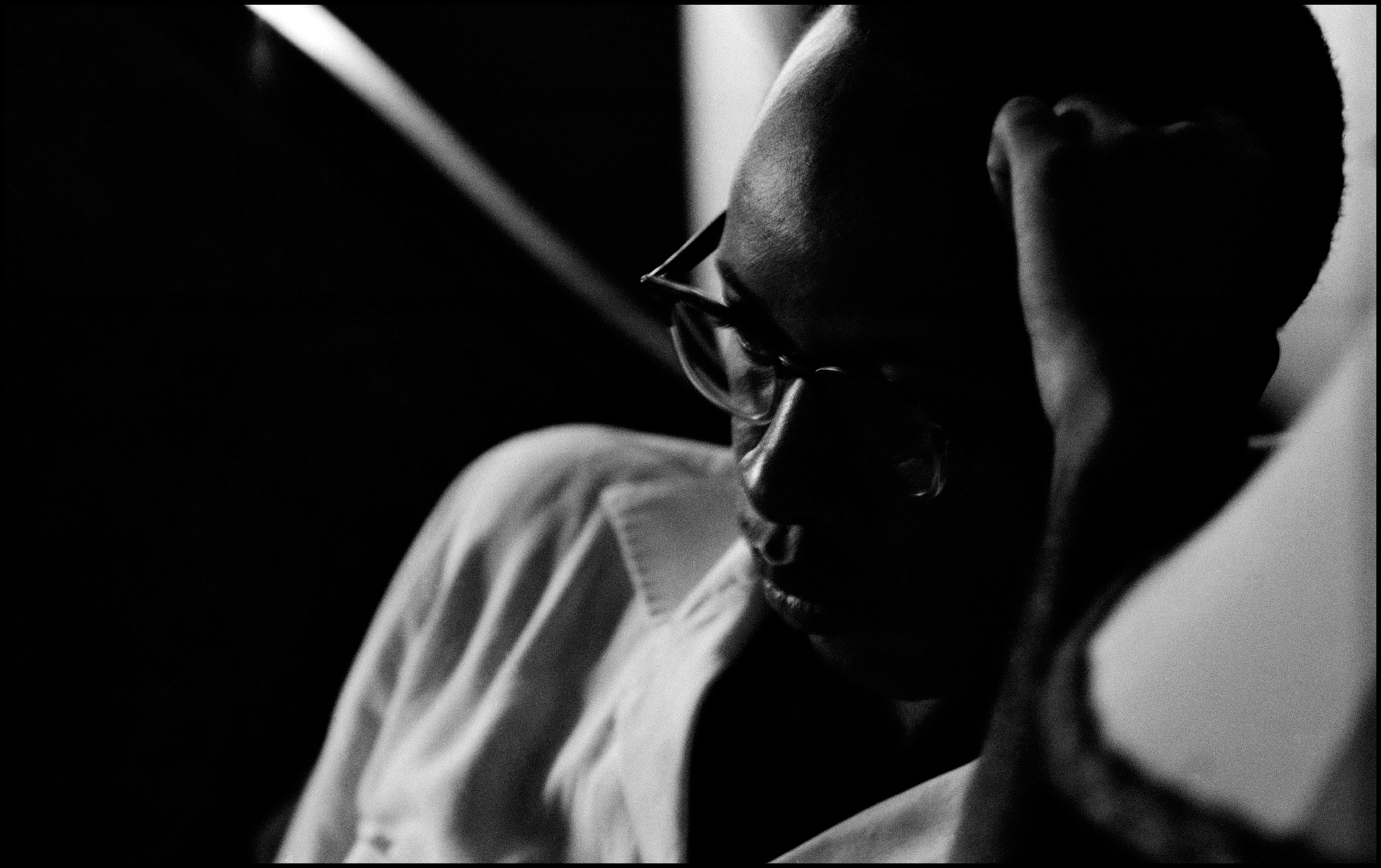

Charles Sherrod, the leader of SNCC’s Southwest Georgia Project, in Albany Georgia, 1962, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 33, dektol.wordpress.com

In the late summer of 1961, Bob Moses had begun a voter registration project in Southwest Mississippi. Charles Sherrod was paying careful attention. Soon, in the spirit of experimentation that was beginning to shape SNCC culture, he and Cordell Reagon began working in Albany, Georgia. Later they were joined by Charles Jones, a protest leader in Charlotte, North Carolina.

W.E.B. DuBois described Southwest Georgia as “a great fertile land, luxuriant with forests of pine, oak, ash, hickory, and poplar, hot with the sun and damp with the rich black swampland; and here the Cotton Kingdom was laid.” It was as violent and resistant to civil rights as Mississippi. With names like “Terrible Terrell,” “Unbearable Baker,” and “Unworthy Worth,” the counties of Southwest Georgia were notorious strongholds of white supremacy and the oppression of Black people. Carolyn Daniels, a beautician who housed SNCC workers, remembers growing up in Terrell County and hearing stories about people she knew getting beaten and lynched.

In the middle of the region sat Albany, a city of 60,000 and roughly 40% Black. Albany tried to cultivate an image distinct from the racial violence that characterized the counties that surrounded it. The city was still racially segregated, however, and Black residents were often subjected to humiliation at the hands of whites.

Georgia Normal and Agricultural College (later Albany State College), 1938, New Georgia Encyclopedia

Nonetheless, it seemed a good place to launch a voter registration effort. Students at the the local Black college, Albany State, were anxious to launch protests against segregation. They were in a rebellious mood toward the conservative campus administration and pushed the college president to address their demands about conditions on campus.

Sherrod and Reagon concluded that it was important to create a mass movement in the regional metropolis before working in the rurals where Black people made up a majority of the population. The duo from SNCC began conversations with students on Albany State’s campus but were quickly kicked out by a nervous school administration. But it was too late, Sherrod wrote, “We delivered the idea that would disrupt the system.”

In mid-November, about a month after their arrival, the Albany Movement was born. It was a coalition of community groups that included the NAACP Youth Council and the Ministerial Alliance. Students, of course, were active in the group, as was the federation of women’s clubs.

Street protest soon began, as did SNCC-led workshops where nonviolence, direct action, and jail-without-bail were discussed and direct action planned. Bernice Johnson attended these nonviolent workshops and recollected that the concept of nonviolence “did not compute for me, so I settled for nonviolence meaning that no matter who hit me, I was not going to hit them back, because I wanted to be in the Movement.” As Sherrod and Cordell Reagon integrated themselves into the community, they plugged into a tradition of resistance older than SNCC which they used to foster and assist a movement against segregation that would shake the very foundations of Albany and open the door to change.

Sources

Charles E. Cobb, On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill).

Carolyn Daniels, “We Just Kept Going,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 152-157.

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972).

Bernice Johnson Reagon, “Uncovered and Without Shelter, I Joined This,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 119-128.

Annette Jones White, “Finding Form for the Expression of my Discontent,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 100-119.

Howard Zinn, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (Chicago, Haymarket Books, 1964).