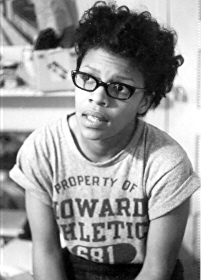

Cynthia Washington

February 22, 1942 – March 2, 2014

“I never was a true believer in nonviolence, but was willing to go along [with it] for the sake of the strategy and goals. [However] we heard that James Chaney had been beaten to death before they shot him. The thought of being beat up, jailed, even being shot, was one kinda thing. The thought of being beaten to death without being able to fight back put the fear of God in me…So, I acquired an automatic handgun to sit in the top of that outstanding black patent and tan handbag that I carried.” — SNCC field secretary Cynthia Washington

Cynthia Washington came to SNCC through the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), the Howard University-based SNCC affiliate that provided a significant core of Black volunteers to the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project. Although she was brought up as part of the “DCBB”–the shorthand Washington D.C. SNCC people used for the D.C. Black Bourgeois–she quickly traded in her city living for Mississippi Delta dust.

Few were more staunchly dedicated than Washington to the people they worked with in the Delta. Her driving skills–critically important if being chased–were among the best. Joanne Gavin recalled that Washington’s application to the summer project listed her skills as being able to “read, write and speak English and drive trucks.”

Washington often dressed in overalls and dungarees and defended people’s right to self-determination and self-defense. She was never much sold on the philosophy of nonviolence. She explained that it would’ve been “an unforgivable sin to willingly let someone kill my mother’s only child without a fight.” Movement colleagues remember her driving around Mississippi with “a fast car and a good gun,” although she never had to use it.

Washington served as a project director in Bolivar County, Mississippi, one of the few women to do so. “I did not see what I was doing as exceptional,” she explained, “The community women I worked with on projects were respected and admired for their strength and endurance…They were typical rather than unusual.”

In 1965, she joined SNCC’s organizing efforts in the Alabama Black Belt and started directing a project in Greene County. Washington, Fay Bellamy, and three male staffers lived in a two-room house with a latrine they dug themselves, two miles off the main road. The Greene County sheriff visited them early on, telling them that as long as they didn’t bring any white people into the county to work with them, he’d give them no problems. They worked to register voters there until the male staffers totaled their car and effectively brought their rural project to an end.

Washington’s consciousness of struggle extended beyond Black struggle. She wrote a memo to SNCC chapters across the country calling on them to boycott Schenley liquors as part of SNCC’s alliance with the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). In September 1965, Latino farm workers joined a strike against grape growers around Delano, California. Schenley Industries owned one of the largest ranches where NFWA was on strike. Washington’s memo explained “the workers have been harassed by strikebreaking tactics reminiscent of the 1930s and with police oppression typical of Birmingham’s Bull Connor and Selma’s Jim Clark.”

Washington challenged the idea of sexism in SNCC, authoring a widely-circulated letter in 1977 that criticized Casey Hayden and Mary King’s claim that there was sexism within the organization. In the letter she wrote, “A number of other Black women also directed their own projects. What Casey and other white women seemed to want [was] an opportunity to prove they could do something other than office work.”

Sources

Lauren Araiza, “Complicating the Beloved Community: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the National Farm Workers Association,” The Struggle in Black and Brown: African American and Mexican American Relations during the Civil Rights Era, edited by Brian D Behnken (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 78-103.

David Barber, A Hard Rain Fell: SDS and Why It Failed (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 102-103.

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

Fay Bellamy Powell, “Playtime is Over,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 473-483.

Belinda Robnett, How Long? How Long?: African-American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 118-119.

Remembrances of Cynthia Washington, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.