November 1966

Lowndes County Freedom Organization becomes Lowndes County Freedom Party

Road sign promoting the Lowndes County Freedom Party during the November elections, 1966, Jim Peppler Southern Courier Photograph Collection, ADAH

In Alabama, candidates for elected office who belong to a political party must be nominated at their party’s convention at a public polling site. Having formed a political party, the only such place in Lowndes was the county courthouse in Hayneville. But when John Hulett, the chairman of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), asked Sheriff Ryals for permission, the sheriff refused, claiming he couldn’t protect them from white violence. Speaking for the rest of the organization, Hulett told him “that we were going to have this meeting, we were going to have it here, on this lawn. And we wouldn’t let anybody scare us off.”

LCFO’s stance that it would hold its convention on the courthouse lawn drew the attention of the Justice Department, which desperately wanted to avoid racial violence. They “began to really panic” Hulett recalled, when he told them that LCFO was determined to use the courthouse lawn and would defend themselves from white violence if necessary. “[I]f shooting takes place, what are [you] going to do?” he was asked by the Justice Department. Hulett responded, “We are going to stay out here [and] we are going to protect ourselves.”

After political wrangling between the Justice Department and the state government, LCFO was allowed to hold its convention at the First Baptist Church, just up the road from the courthouse. For Hulett, the episode showed the strength of Black solidarity. “When the people are together, they can do a lot of things.”

On May 3, 1966, LCFO had its nominating convention at the church. Some 900 Black people turned out for it. Sidney Logan Jr. won the nomination for sheriff; Frank Miles, Jr. for tax collector; Alice Moore for tax assessor; and Emory Ross for coroner. Robert Logan, John Hinston, and Willie Mae Strickland were elected as candidates for the school board.

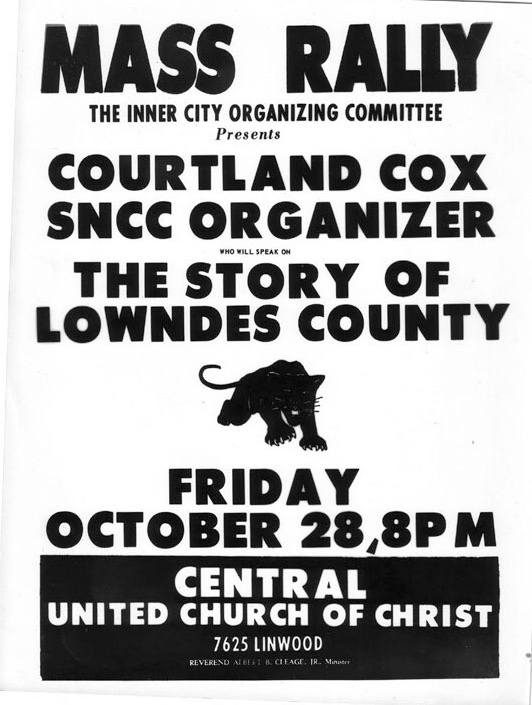

In pointing out the significance of the meeting, SNCC’s Stokely Carmichael explained, “This meeting is very different from any other meeting taking place in the state because the candidates are not important. It is the organization that is important.” The collective interests of the Black community were placed before the political aspirations of the individuals seeking office.

LCFO spent the summer of 1966 galvanizing support for the upcoming election. SNCC workers and local activists canvassed some of the poorest Black communities and talked with people about improving Black schools, halting unlawful evictions, and taxing wealthy landowners. John Hulett remembered, “Once you start telling people this they start to think about it. You may have to leave them for a day or two, but you keep going back to them and finally you’re able to pull most of these people in.” Canvassers also encouraged Black people to register to vote, and, by November, 2,800 were on the voting rolls–about half of the county’s eligible Black voting population.

People lined up to vote for the county elections in Lowndes, Alabama, November 1966, Jim Peppler Southern Courier Photograph Collection, ADAH

The night before the election, hundreds of movement supporters came to Mt. Moriah Church for a final mass meeting. The crowd was both proud and confident about what they had accomplished. A year earlier, Lowndes only had one Black voter; now Black people were running their own candidates for office. Carmichael gave words to the people’s thoughts when he exclaimed, “We are going to say goodbye to shacks, dirt roads, poor schools. We say to those who don’t remember – you better remember, because if you don’t move on over, we are going to move over you.”

LCFO candidates lost the election that year for a number of reasons. Some Black voters stayed home on election day, fearing white retaliatory violence. Other Black people, especially tenant farmers, were coerced into voting for white candidates. Ironically, some white landlords even bused their tenants to the polls to vote for the white candidates. Despite the turnout, the LCFO candidates made a respectable showing. They all received well above 20% of the vote, making LCFO eligible to become a political party. The organization changed its name to the Lowndes County Freedom Party as a result. Five years later, LCFP candidate John Hulett was elected county sheriff, and Mr. Charles Smith became the county commissioner. “This was the first time that black peoples in this county came together to make the choice of their own candidates for public office,” recalled Hulett. “That is why is this important.”

Sources

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (New York: Vintage Books, 1967).

Stokely Carmichael with Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (New York: Scribner, 2003).

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2008).

Cheryl Greenberg, ed., A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

Henry Hampton, et al., eds., Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s (New York: Bantam Books, 1990).

Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt (New York: New York University Press, 2009).

Paniel E. Joseph, Stokely: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas, 2014).

Interview with Courtland Cox by Joseph Mosnier, July 8, 2011, Civil Rights History Project, Library of Congress.