August 1966

New York Times publishes Atlanta Project Statement

On August 5, 1966, the New York Times published excerpts from a position paper on Black Power written by members of SNCC’s Atlanta Project. Although it was not an official policy statement, the Times ignored that fact. Instead, the Times used the paper’s call for Black-led organizing and consciousness-raising and its suggestion that whites should organize in white communities as proof that SNCC was maliciously anti-white. “Regardless of other interpretations that could reasonably be offered of the term ‘black power,’ Mr. Carmichael and his SNCC associates clearly intend to mean Negro nationalism and separatism along racial lines–a hopeless, futile, destructive course expressive merely of a sense of black importance,” the editors wrote.

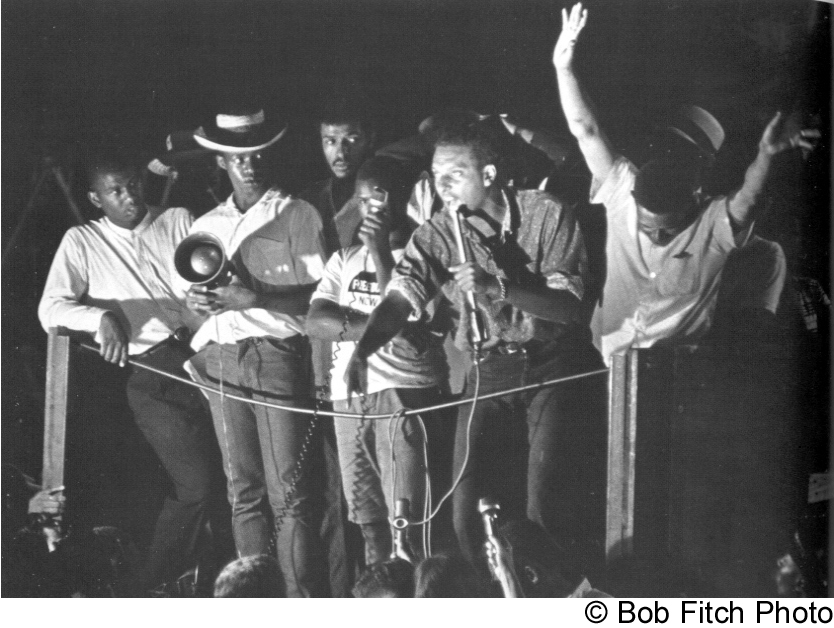

SNCC’s Stokely Carmichael calls for “Black Power” in Greenwood, Mississippi on Meredith March, June 1966, Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Stanford University

The term Black Power had exploded into the nation’s consciousness two months earlier when Stokely Carmichael shouted, “We want Black Power!” at a rally in Greenwood, Mississippi during the Meredith March Against Fear. The crowd had roared back its support. Many liberal whites as well as most of the national civil rights establishment responded by accusing SNCC of a narrow Black nationalism intent on violence. The NAACP’s Roy Wilkins, described it as a call for “Black death.” But idea had grown out of SNCC’s grassroots organizing efforts in the Mississippi Delta, Southwest Georgia, and Lowndes County, Alabama. It expressed, as a slogan, a commitment to meaningful Black empowerment.

It was within this context that the Atlanta Project had developed its position paper on Black Power while working in Vine City, one of the poorest areas of Atlanta. From the beginning, Atlanta Project staffers worked to build a sense of Black pride in the local people they were working with, and their concern about the role of whites emerged from their day-to-day organizing. Gwen Robinson (later Zoharah Simmons) and other organizers witnessed how white people organizing in Black communities reinforced internalized racism. When a Black person entered a SNCC office and saw a white person, for example, they assumed that the white person was in charge. The Atlanta Project wrote a position paper that clarified their commitment to developing local leaders and addressed the role of whites in the Movement. “White people who desire change in this country should go, where that problem (of racism) is most manifest,” Atlanta project staffers wrote. “The white people should go into white communities.”

The New York Times interpreted the Atlanta Project’s desire to have white people organize white communities as kicking white people out of SNCC. “Using their position paper to popularize their views, the ‘black consciousness’ advocates succeeded in persuading the full membership to adopt a formal policy of excluding whites from policy-making and organization roles within the committee,” the newspaper wrote.

The Atlanta Project statement was indeed contentious within SNCC and the Times emphasized that SNCC advocates of nonviolence as a way of life, like former chairman John Lewis, opposed what the newspaper characterized as “black power philosophy.” It ignored the fact that the Atlanta paper was part of a larger discussion in SNCC about its future direction, And it ignored the fact that a ranged of SNCC organizers–some committed philosophically to nonviolence–believed that whites could work in Black communities without undermining grassroots leadership.

The article’s publication had an immediate impact on SNCC’s work. Many white donors withdrew their support from the organization. The misleading and negative coverage of Black Power, along with SNCC’s statement against the War in Vietnam, placed severe financial strain on the organization. The Atlanta Project statement was unintentionally prophetic. “If we continue to rely upon white financial support,” it said, “we will find ourselves entwined in the tentacles of the white power complex that controls this country.”

Sources

Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt (New York and London: New York University Press, 2009), 185-192.

Gene Roberts, “Black Power Idea Long in Planning,” New York Times, August 5, 1966.

Center for Documentary Studies, SNCC Critical Oral Histories Conference, July 2016, Duke University.

Letter from Roy Wilkins to NAACP supporters re: Black Power, October 17, 1966, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website, Tougaloo College.

Letter to editor by Ivanhoe Donaldson to New York Times, October 1966, Folder 252253-061-0855, SNCC Papers, ProQuest History Vault.