National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

Throughout the 20th century, the NAACP was the main vehicle in the struggle for civil rights both nationally and in the South. It fought for anti-lynching legislation and fought for equal opportunity in all walks of life. Its legal attack resulted in school segregation being outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954.

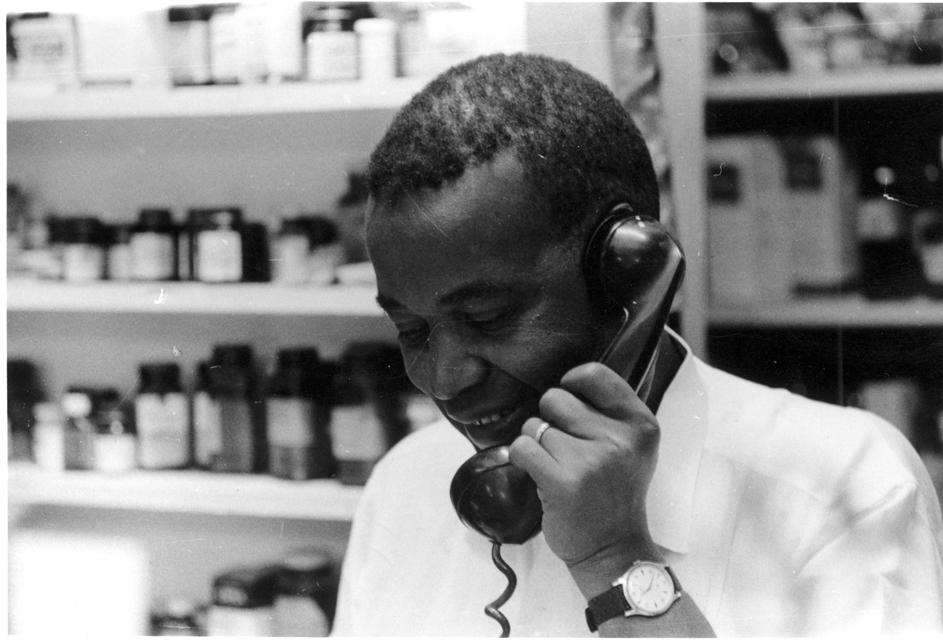

Aaron Henry, Coahoma County NAACP branch president, on the telephone at his drug store in Clarksdale, 1964, Margaret J. Hazelton Freedom Summer Collection, USM

Sometimes, however, there seemed to be two NAACPs. The national NAACP headquartered in New York, was not always in complete sync with its local branches in the South, and most of the organization operated at the local branch level. These local chapters were the “lifeblood” of the organization, forming most of its membership and engaging in local activism against racial discrimination. Many of these branch leaders were frustrated by the national organization’s legalistic approach that seemed to exclude engagement with their concerns. As Amzie Moore, president of the Cleveland, Mississippi branch remembered it, national NAACP president Roy Wilkins would “fly down and hold our conferences and hold our annual ‘days’ and raise our freedom money and be advised by different people outa [sic] New York office. And that was it.”

The national NAACP office wanted to concentrate on eliminating racial oppression in the border states prior to attacking the white supremacist strongholds of the Deep South where victory seemed unlikely. However, in the decades after World War II, veterans returning home began to establish local NAACP branches. In Mississippi, ten new branches were established between 1945 and 1947. Aaron Henry, a Clarksdale-native, had earned a degree in pharmacy after returning from the service and opened a drugstore in his hometown. When he helped form the local chapter of the NAACP, of which he quickly became president, he saw it as a way “at long last to get legal assistance when we needed it and perhaps remedy the frequent abuses our people suffered at the hands of whites.”

During the fifties, the NAACP provided a home for a variety of local activists and helped to create a kind of co-optable network “composed of like-minded individuals predisposed by virtue of their background to being receptive to the ideas of a new movement.” These same local NAACP activists formed groups like the Regional Council of Negro Leadership in Mississippi, the Veterans League in Georgia, and the Progressive Democratic Party in South Carolina. In the 1960s, these leaders provided crucial support and guidance to SNCC field workers. Amzie Moore, in particular, was instrumental in bringing SNCC into Mississippi and putting voter registration on SNCC’s table. “I found that SNCC was for business, live or die, sink or swim, survive or perish,” Moore explained. He, like other NAACP leaders as SNCC expanded its organizing efforts, introduced SNCC field secretaries to his extensive movement network.

These NAACP activists, along with local youths, became the next generation of civil rights activists. For instance, the Ladner sisters, Joyce and Dorie, both of whom became active in SNCC during the sixties, were introduced to the Movement through the NAACP’s Medgar Evers and the Hattiesburg, Mississippi NAACP branch president, Vernon Dahmer. “We were fifteen, sixteen, seventeen years old, and they were taking up time with us to try and teach us,” Dorie Ladner remembered. These local NAACP activists opened up movement networks that had been in place long before SNCC, networks that would facilitate the voter registration efforts of SNCC everywhere the organization worked.

Sources

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Aaron Henry and Constance Curry, Aaron Henry: The Fire Ever Burning (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2000), 73.

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Howell Raines, My Soul is Rested: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement in the Deep South (New York: G.P. Putnam’s and Sons, 1977).