Learning Toolkit Resources

Freedom Songs

Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around

SNCC Freedom Singers

Ella’s Song

Resistance Revival Chorus

Engage With the Sources: Stokely’s Speech Class, Notes by Jane Stembridge, 1965

Freedom Songs

Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around

SNCC Freedom Singers

Ella’s Song

Resistance Revival Chorus

Engage With the Sources: Stokely’s Speech Class, Notes by Jane Stembridge, 1965

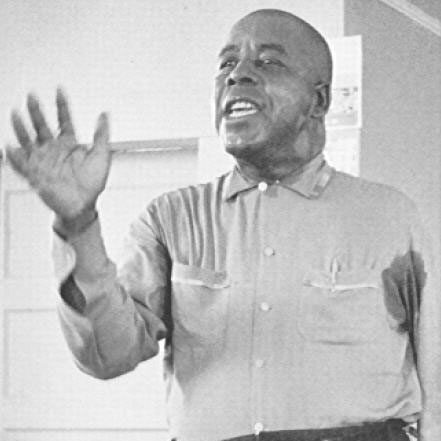

This class illustrates the way many of the ideas of Black Power were present in SNCC’s educational and cultural work even before Stokely Carmichael popularized the phrase Black Power. Read a transcript of Stokely Carmichael’s 1965 class, described above.

Think about these questions:

- How do the students initially respond?

- How does Carmichael help them consider and rethink assumptions about language and what is “proper”?

- What does this class suggest about SNCC’s approach to freedom teaching compared with traditional academic teaching

Engage With the Sources: “What We Want” by Stokely Carmichael, New York Review of Books, Sep. 1966

When Stokely Carmichael called for Black Power, many politicians and reporters attacked SNCC, claiming that Black Power was anti-white, violent, and reverse racism. Read excerpts of “What We Want” that Carmichael wrote to explain his thinking and that of many of his colleagues in SNCC.

Excerpts from “What We Want”

Think about these questions:

- How does Carmichael define “Black Power”?

- What does he say about the kind of economics and politics SNCC was calling for when they used the phrase “Black Power”?

- What role does he say that whites should play?

Read the full version of “What We Want”

Stokely Carmichael, What We Want; 1966, Michael J. Miller Papers, USM

Activist Insights Across Generations

In a recent conversation SNCC’s Courtland Cox and two younger activists, Nsé Ufot and Charles Taylor, discussed the importance of a new southern political strategy that centers the thinking and priorities of Black southern communities.

Crosby, Emilye. “The Rhetoric and the Reality of the New Southern Strategy: Courtland Cox, Nsé Ufot, and Charles V. Taylor Jr. in Conversation,” Southern Cultures, vol. 30, no. 1 (Spring 2024), 98-115.

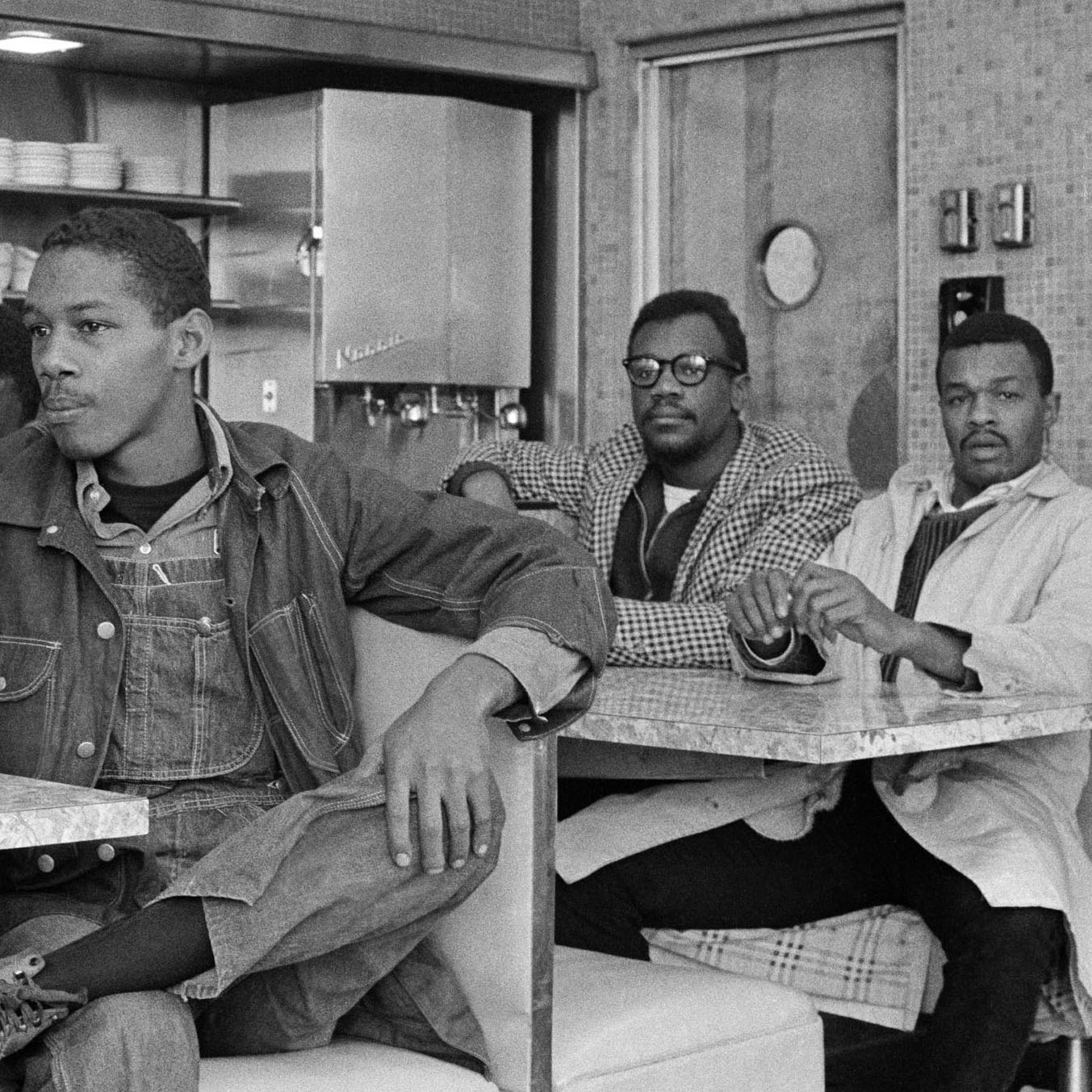

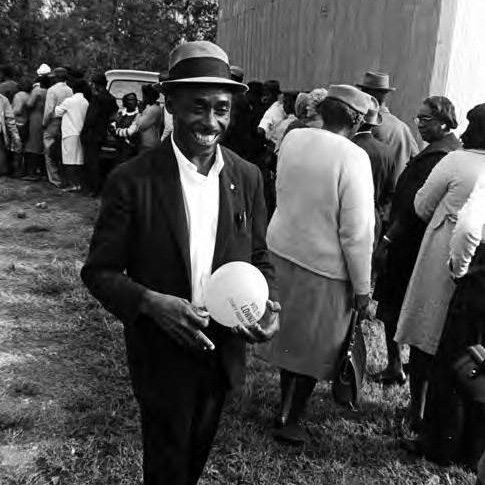

Meet SNCC Staffers

Match the following descriptions with the SNCC staffers they describe. Click on their images and read their profiles to learn about these—and other—SNCC staffers. If you have time, explore the related primary sources. What did you learn about SNCC and Black Power?

Who am I?

I took a leave from graduate school at the University of California, Berkley to work in the Lowndes County Movement. Influenced by my discussions in Paris with Congolese and Algerian students and by the death of Tuskegee student Sammy Younge, I drafted SNCC’s anti-Vietnam War statement.

Who am I?

I am one of the SNCC people who took my SNCC values into politics, and I served on the Washington, D.C. board of education and its city council. As part of SNCC, I organized in Holly Springs, Mississippi, and helped build the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union as a way to begin addressing the important economic issues facing Black Mississippians.

Who am I?

I joined the Children’s March in Birmingham and became deeply involved in the movement as a Tuskegee student, eventually dropping out and working full-time for SNCC in Lowndes County, Alabama. Among other things, I helped develop political education materials, including a cartoon called “Us Colored People.”

Who am I?

I was a landowner and one of the first people in my community to try to register to vote. In response, my home was bombed. Unlike SNCC workers, I was never committed to nonviolence, even as a tactic. When my house was firebombed and shot at, I used a gun to protect my wife and daughter.

Who am I?

I worked with the NAACP in Birmingham and led a voter registration drive in my home community of Lowndes County when I returned in the 1960s. I was one of the early leaders of the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP) and although we failed to win in our first election, I became the community’s first Black sheriff, running on the LCFP ticket.

Who am I?

I am a military veteran born in the North and, in 1965, was delighted to help bring Malcolm X to Selma, Alabama, where he spoke to a transfixed audience. I managed the Selma office and then worked in the field in Green County, Alabama, before moving on to the Atlanta office. After SNCC, I continued to work with movement organizations like Highlander and the Institute of the Black World.

Who am I?

As a high school student, I asked my family to provide housing for SNCC and my family welcomed SNCC, even when we faced economic terrorism and had to use guns to defend our home.

Who am I?

I was fired and evicted for trying to register to vote, but I never turned back and devoted the rest of my life to the movement. I was known for my singing, and my persuasive testimony at the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) Convention in Atlantic City was broadcast around the country and generated significant support for the MFDP.

Who am I?

As a college student, I was active in NAG (the Nonviolent Action Group), a Howard University SNCC affiliate. I am particularly passionate about the importance of economic empowerment. In addition to helping organize the Lowndes County Freedom Party, I represented SNCC at the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal and helped organize the 6th Pan African Congress.

Who am I?

Growing up, I divided my time between Detroit and Alabama, where my grandparents introduced me to the movement. With other Tuskegee College students, I protested for voting rights in Montgomery and later became chair of the Black Women’s Liberation Committee.

Who am I?

I was born in Trinidad and grew up in New York before I began working with SNCC as a first year college student at Howard University in 1960. Although I joined the freedom rides, worked on voter registration, and was one of the leaders during the Mississippi Summer Project, I am best known for my work in Lowndes County and leading the call for Black Power.

Who am I?

Though Stokely Carmichael is known for Black Power, I pushed him to use the phrase during the Meredith March. I never really believed in philosophical nonviolence and worked in a number of communities with SNCC, including Southwest Georgia, and Lowndes County, Alabama.

Black Power Songs

Mississippi Goddam

Nina Simone

Say It Loud

James Brown

Works Cited

Alice Moore profile, SNCC Digital Gateway, SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University.

Carmichael, Stokely. “What We Want,” New York Review of Books, Sept. 1966.

Cox, Courtland. “What Would It Profit a Man to Have the Vote and Not Be Able to Control It?,” 1965 or 1966, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/courtcox.htm.

Crosby, Emilye, ed. “The Rhetoric and the Reality of the New Southern Strategy: A Conversation between Courtland Cox, Nsé Ufot, and Charles Taylor.” Southern Cultures, 30 (no. 1). https://www.southerncultures.org/article/cox-ufot-taylor/.

Emergence of Black Power, SNCC Digital Gateway, SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University.

House, Gloria. “We’ll Never Turn Back, in Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith Holsaert, et al., 503-514. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Leflore County cuts off surplus commodities, SNCC Digital Gateway, SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University.

March on Washington speech, SNCC Digital Gateway, SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University.

Wood, Julia Erin. “’What That Meant to Me’: SNCC Women, the 1964 Guinea Trip, and Black Internationalism.” In To Turn the Whole World Over: Black Women and Internationalism, edited by Keisha N. Blain and Tiffany M. Gill, 219-234. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2019.