January 1964

Freedom Day in Hattiesburg

“We have come here tonight to renew our struggle,” Ella Baker told the audience overflowing into the aisles of St. Paul’s Methodist Church in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Many in the crowd were from nearby Palmer’s Crossing, a historically-Black community just south of Hattiesburg and a center of movement activity.

Fannie Lou Hamer picketing at Forrest County courthouse on Freedom Day in Hattiesburg, January, 1964, Matt Herron, crmvet.org

Many of the Forrest County Movement’s leaders had come from this community: Victoria Jackson Gray, who first became involved with SCLC as a Citizenship School teacher and later a SNCC field organizer and MFDP leader. Others, including John Henry Gould, Johnnie Mae Walker, and NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer, who owned land in Kelly Settlement just outside of town, founded the Forrest County Voters League. Two of SNCC’s most important young leaders, Joyce and Dorie Ladner were also from Palmer’s Crossing.

Those gathered in St. Paul’s intended to participate in what would be one of the largest planned protests of the Civil Rights Movement to date–a “Freedom Day.” The first Freedom Day had happened in Selma, Alabama the previous fall, and Hattiesburg, or “Hub City,” was chosen as the site for the second one because of local circuit clerk Theron Lynd’s continuing refusal to register Black voters. His intransigence had already brought a federal contempt citation. But he continued to resist registering potential Black voters. So local activists decided that the time to draw attention to their struggle had come. Creating further incentive over half of the county’s eligible Black voters had turned out for the November 1963 Freedom Ballot. This turnout convinced Vernon Dahmer that the time was right to stage a larger protest.

Singing on the Forrest County courthouse steps on Freedom Day in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, January 22, 1964, Danny Lyon, Bleakbeauty.com

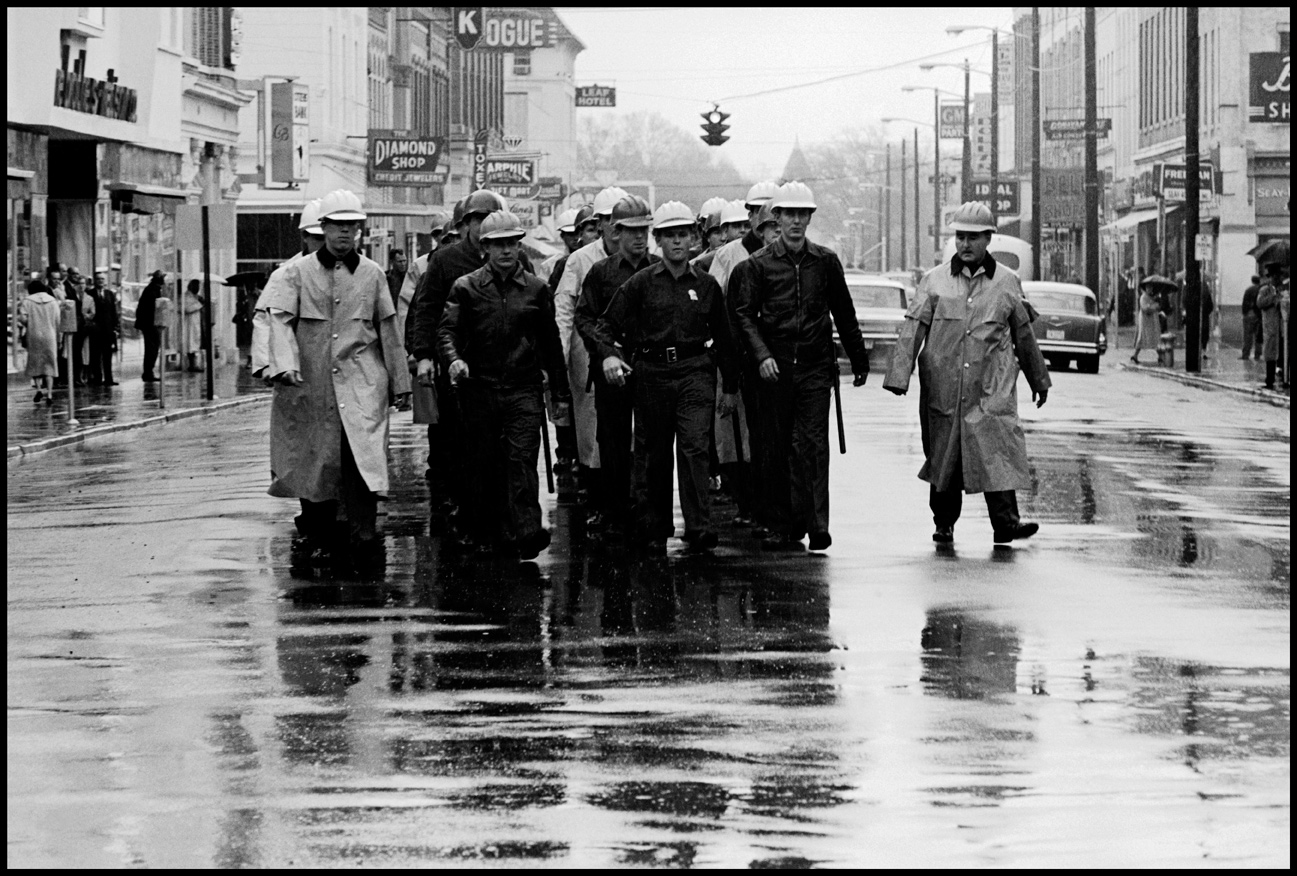

The morning of the protest, a cold rain fell on Hattiesburg. It was January 22, 1964. Students held placards with SNCC’s new slogan, “One Man, One Vote,” while adults lined up in front of the door to the county registrar’s office. The protesters were met by dozens of state patrol officers, sheriff’s deputies, and volunteer auxiliary police. The sheriff, Bud Gray, told the assembled men and women through a bullhorn, “this is the Hattiesburg Police Department. We’re ordering you to disperse. Clear the sidewalk!” Sheriff Gray did not force the protesters to leave, and when it became clear that violence was not forthcoming, the ranks of the protesters doubled. By mid-afternoon, the line to register to vote stretched nearly two blocks down the street.

In spite of only being allowed into the county registrar’s office four at a time, nearly 150 people made their way before Lynd to register to vote by the end of Freedom Day. Only three people were arrested, and despite the heavy police presence, no violence occurred. Freedom Day in Hattiesburg inspired later protests in Greenwood in March and even in the notoriously violent Southwest Mississippi town of Liberty, in April. With a significant presence of white northerners, Freedom Day also signaled the beginning of what would be SNCC and the Mississippi Movement’s most ambitious effort in 1964: the Mississippi Summer Project.

Sources

Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998).

David J Dennis, “Unsung Heroes of 1964 Freedom Summer” The Southern Quarterly (Fall 2014), 44-50.

Mark Newman, Divine Agitators: The Delta Ministry and Civil Rights in Mississippi (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990).

Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

“Freedom Day in Hattiesburg (Jan),” Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.