January 1964

SNCC debates Freedom Summer

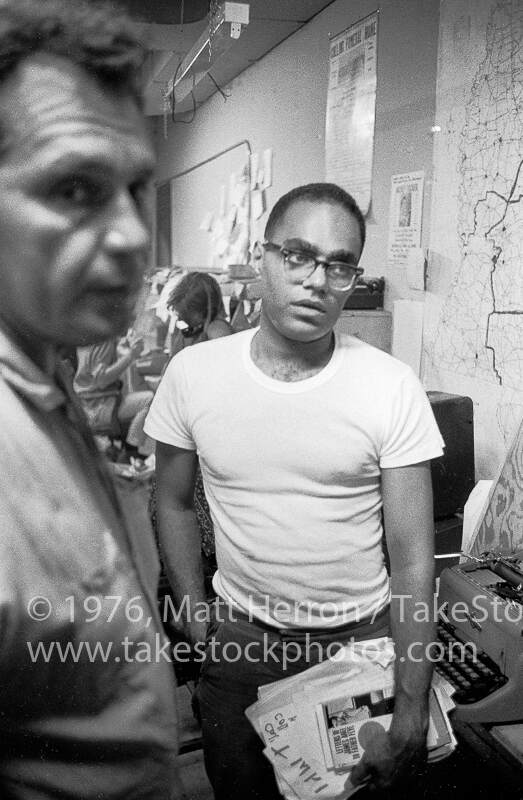

Freedom Summer director Bob Moses at COFO’s headquarters in Jackson, Mississippi, during the summer of 1964, Matt Herron, Take Stock

The idea was first presented to field staff during a five-day workshop in mid-November 1963 in Greenville, Mississippi to evaluate the “Freedom Vote” that had taken place the month before. Nearly 80,000 Black Mississippians had cast ballots.

The presence of white student volunteers from Stanford and Yale throughout the effort had led to unprecedented media coverage and even spurred the Justice Department to greater activity in the state. An idea emerged from this effort: why not capitalize on that momentum and send an even larger group of white volunteers to Mississippi that summer? Use the nation’s racism to spark outside intervention.

The documented violence that local Black citizens and SNCC workers had suffered in the previous years was escalating and had only met federal inaction. The national attention brought by a significant presence of white volunteers could potentially increase protections for local communities and civil rights workers.

Many staff veterans were immediately opposed to the concept. Charlie Cobb, Ivanhoe Donaldson, MacArthur Cotton, and Sam Block argued that the entire premise of the strategy contradicted SNCC’s principle of developing local leaders. Willie Peacock and Hollis Watkins recalled how many in Greenwood had responded to the Stanford and Yale students just because they were white, reinforcing a sense of inferiority. There was concern that white volunteers would gravitate towards leadership positions, destroying the grassroots organizations the veteran staff had worked so hard to build.

On the other hand, local people like Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer and Amzie Moore almost unanimously supported the idea of bringing in white volunteers. “If we’re trying to break down segregation, we can’t segregate ourselves,” Mrs. Hamer reminded the group. Moore and SNCC staffer Lawrence Guyot argued that the potential benefits far outweighed the risks. If nothing else, the increased media attention could finally shed a national spotlight on the realities of their oppression.

The debate within SNCC and COFO over the summer project carried on for the rest of the year. The events surrounding a COFO staff meeting in Hattiesburg ultimately tipped the scale for the summer project. On the morning of February 1, 1964, the meeting was interrupted by a telephone call bringing the news that Louis Allen had been found dead, shot in front of his truck at his home in Amite County.

The Black logger had suffered constant harassment after witnessing the murder of Herbert Lee. It became known that Allen was willing to testify against Eugene Hurst, who had murdered Lee, if given federal protection. He received none. SNCC Mississippi project director Bob Moses began to push for the summer project, stressing the need to call attention to the continuing violence in Mississippi.

In addition, support for the project from local leaders like Mrs. Hamer carried great weight among veteran staff. No matter what they felt, the staff was not going to fight with local people about the project. By the end of December COFO and SNCC were moving forward. The initial plan was to bring roughly 100 white volunteers to the state. This number quickly grew to 1,000.

The misgivings about the presence of white volunteers remained, but having now decided to move forward, all staff committed to putting their best efforts into ensuring its success. The summer project became Freedom Summer.

Sources

Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 1988), 920.

Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981).

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Wesley Hogan, Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC’s Dream for America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 154.

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 396.

Laura Visser-Maessen, Robert Parris Moses: A Life in Civil Rights and Leadership at the Grassroots (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 77-78, 183- 185.