Harry Belafonte

March 1, 1927 – April 25, 2023

Raised in Harlem, New York

Harry Belafonte felt strongly about the need for a radical voice in the Movement. He saw the young people of SNCC filling that role. “Those students would have a profound impact on my life – as I would on theirs,” and in 1961, Belafonte wrote a personal check to the amount of $40,000 that got SNCC on its feet and enabled SNCC’s work in the rural South in the organization’s earliest days.

Belafonte used his art as a means of amplifying voices in the struggles in the United States, the Caribbean, and Africa. Black struggle would importantly contribute to the future shape of the United States, he felt: “I grapple with it so hard because I really believe in the potential of this country. And this country has not realized its potential, it has not even begun to scratch the surface.” Belafonte was always conscious of the content and message of his work and constantly pushed the boundaries of mainstream media.

Drawing on his access as Black celebrity, Belafonte was able to support the Southern Movement. This became especially important shortly after the start of the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project. When the murdered bodies of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were finally found on August 4, 1964, Belafonte received a telephone call from SNCC’s James Forman. He told Belafonte that they were going to run out of money in Mississippi within the next 72 hours. COFO, said Forman, did not have the resources to keep them in the state.

Belafonte was able to raise $70,000 in two days. He knew he would have to supply the money in person, and so he and actor Sidney Poitier personally brought the money – in cash – to summer project headquarters in Greenwood, Mississippi. SNCC field secretary Willie Blue had picked them up. It was late at night, and they were ambushed by Ku Klux Klansmen, who used a pickup truck to try to ram them off the road. Eventually several SNCC vehicles came and escorted them safely into Greenwood. While in the Delta, Belafonte stayed with a local family and participated in SNCC and COFO’s day-to-day work on the ground.

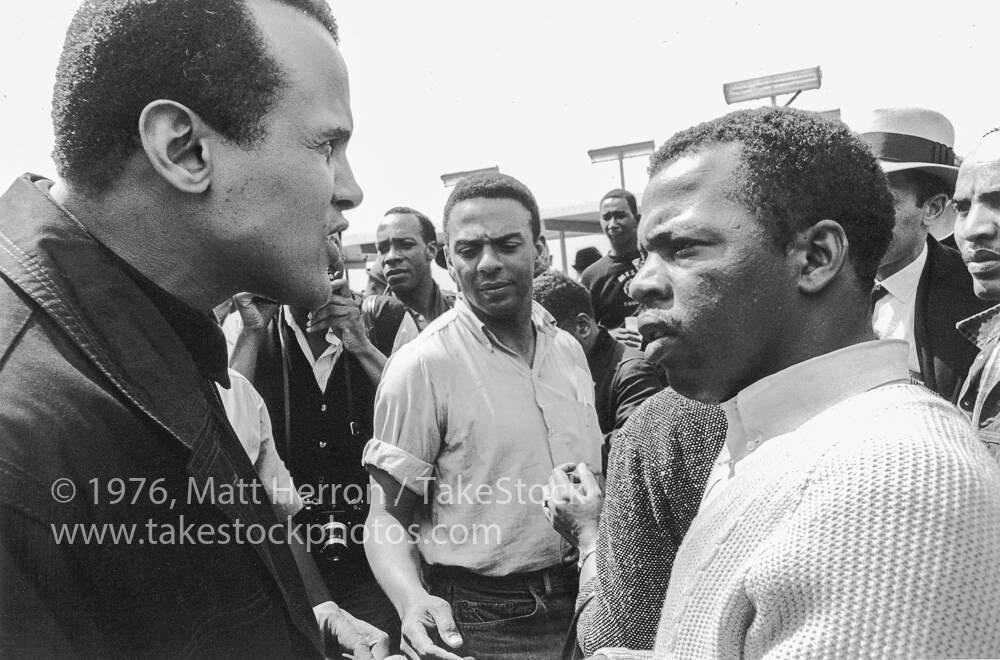

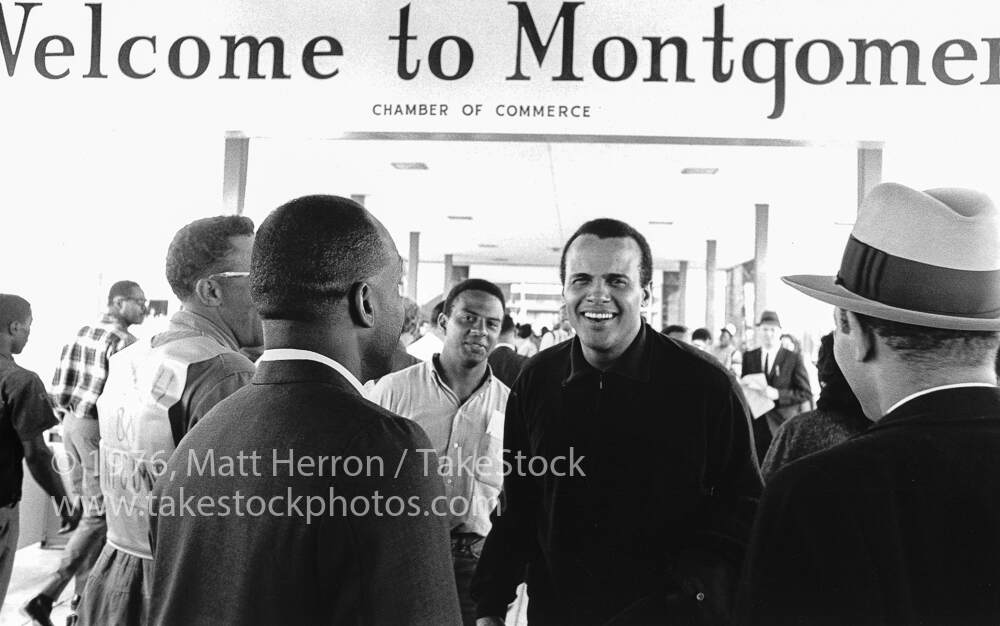

Harry Belafonte comes to Montgomery for the Selma-to-Montgomery March, March 21, 1965, Matt Herron, Take Stock

Belafonte, who had contacts with the government of Guinea, used the extra money that had been raised to take a group of SNCC members to Africa that September, following the MFDP’s convention challenge. The trip, Belafonte hoped, would recharge the SNCC activists, some of whom were experiencing battle fatigue from working in the Deep South. He also wanted the SNCC activists to see an emerging African nation with Black people in positions of power. “I saw black men flying the airplanes, driving buses, sitting behind big desks in the bank and just doing everything that I was used to seeing white people do,” remembered Fannie Lou Hamer. Others on the delegation included Bob and Dona Moses, Jim Forman, Julian Bond, John Lewis, Prathia Hall, Ruby Doris Robinson, Bill Hansen, Donald Harris, and Matthew Jones. This trip, although coming at a time when SNCC was debating the direction it wanted to head in, was essential in broadening the organization’s outlook and preparing these veterans for the long work of the Movement ahead.

Sources

Harry Belafonte, My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race, and Defiance (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011).

Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981).

Interview with Harry Belafonte by Blackside, Inc., May 15, 1989, Eyes on the Prize, Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University.