September 1964

SNCC delegation travels to Africa

Following the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer and the MFDP Convention Challenge in Atlantic City, New Jersey, an uncertainty about where to go next permeated much of the discussion and debate in SNCC. Battle fatigue from working in some of the most dangerous and violent areas in the Deep South was part of the problem. New ideas were needed, and performer Harry Belafonte offered to send a SNCC delegation to Guinea to observe and exchange ideas with leaders in the newly-formed African nation.

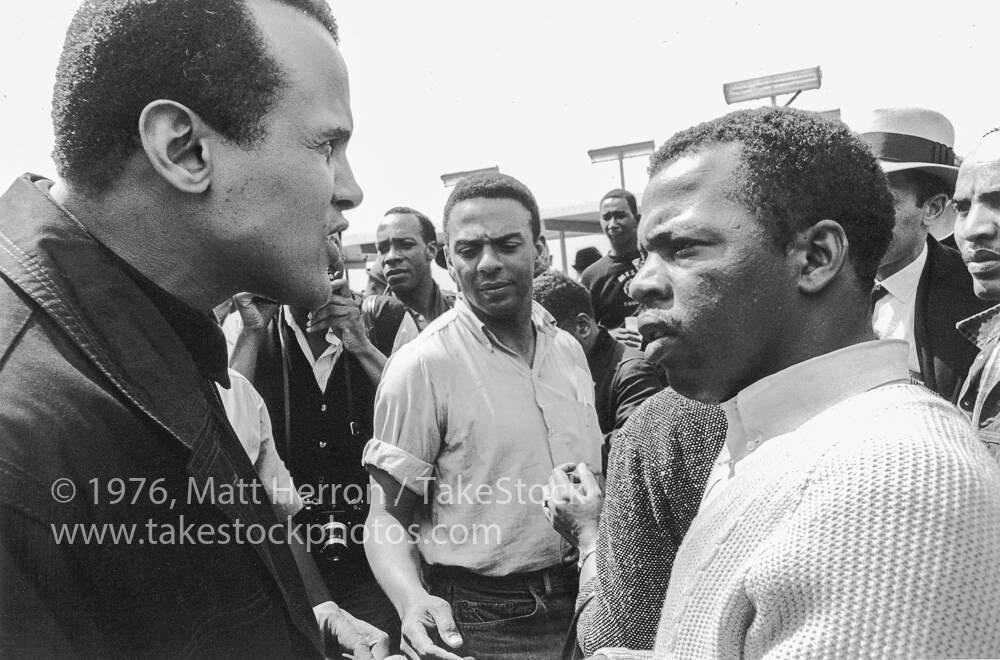

SNCC’s chairman John Lewis remembered he “leaped at the chance” to spend three weeks in Africa in the company of President Sekou Toure, an inspiring hero for many of the student organizers. It wasn’t easy for SNCC to narrow its delegation down to just eleven people; everybody wanted to participate in the organization’s first trip to the continent.

Africa loomed large in the imaginations of many SNCC workers, who had grown up as the continent’s anti-colonial struggles unfolded and were reported on by the U.S. Black press. “Liberation was in the air,” remembered Stokely Carmichael, “and the impression on me was profound.”

Before becoming part of the organization, many in SNCC had already developed a keen interest in African independence movements, which intensified with their work in the South in the early sixties. As a teenager in Cleveland, Ohio, Phil Hutchings, a future SNCC chairman, joined his high school’s chapter of the World Council of Human Affairs and participated in a debate about the merits of the Algerian War. He recalled, “It was getting me into some of the broader stuff of the world … and so I look back on it as a kind of important beginning.”

Under the direction of Jim Forman, SNCC maintained relationships with African delegations in the United Nations and African student groups to bolster international support for its desegregation and voter registration campaigns in the South. SNCC members occasionally met with visiting African dignitaries, like Kenyan leader Oginga Odinga, even taking some of them on sit-in demonstrations to get a first-hand experience of Jim Crow.

African anti-colonial struggles helped frame SNCC’s struggle against white supremacy in America. “One Man, One Vote,” a rallying cry in African anti-colonial struggles, was adopted by SNCC as the slogan for its voter registration work. Whether through interpersonal relationships or the appropriation of African liberation rhetoric, SNCC understood its struggle was of international dimensions, though this took on a much sharper image after SNCC sent its first delegation to Guinea.

The group of eleven, which included Jim Forman, John Lewis, Bob Moses, Dona Richards Moses, Julian Bond, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, Donald Harris, Bill Hansen, Prathia Hall, Matthew Jones, and Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, arrived in Conakry in September of 1964. The group attended the grand opening of a new sports stadium, visited a printing plant named after the fallen Congolese freedom fighter Patrice Lumumba, and toured a match factory. They also enjoyed nightly cultural events and galas. According to Forman, they were watching “a new society being built.” “The Guineans had to start from scratch in every area of national life–and they survived,” recalled Forman, which filled the group with a sense of pride and inspiration.

The visit to Africa exposed SNCC to a larger world of revolutionary thought and struggle and strengthened the organization’s resolve to connect its fight against domestic racism with anti-colonial endeavors abroad. Cleveland Sellers explained, “We’re beginning to expand our horizon, beginning to talk about similarities between the struggle for independence in Africa and the struggle for the right to vote in Mississippi.” For John Lewis and SNCC field secretary Donald Harris, the trip illuminated “the necessity of a strong link between the Freedom Movement here and the various Liberation Movements in Africa.” This marked a new political direction for SNCC and placed the organization on the world stage of revolution.

Sources

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Washington, DC: Open Hand Pub., 1985).

James Forman, “Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Brief Report on Guinea,” 1964, The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Account from the Black Freedom Struggle, 1954-1960, edited by Clayborne Carson, et al. (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 190-195

John Lewis and Donald Harris, “The Trip,” December 14, 1964, The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Account from the Black Freedom Struggle, 1954-1960, edited by Clayborne Carson, et al. (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 195-200.

Fanon Che Wilkins, “The Making of Black Internationalists: SNCC and Africa Before the Launching of Black Power, 1960-1965, Journal of African American History (Autumn 2007), 467-490.