May 1967

Dottie & Bob Zellner present GROW proposal

In the mid-sixties, SNCC’s thinking increasingly turned to the idea of whites organizing in white communities. A more focused “Black consciousness” was emerging, and SNCC activists were less interested in trying to appeal to the nation’s white conscience and placing greater emphasis on the building of cultural, economic, and political institutions within the Black community that could give power to disenfranchised African Americans at the grassroots level.

Consequently, the role of whites within SNCC and the broader Black Freedom Struggle was at a crossroads. Some Black organizers felt that the presence of white activists ran counter to SNCC’s efforts at developing Black consciousness and power. At its Peg Leg Bates meeting in December 1966, SNCC stripped its remaining white members of voting privileges within the organization and asked them to organize in the white community, where racism originated. This sentiment was echoed by longtime white activists, like SCEF’s Anne Braden, who declared, “It is time that white people who care address themselves to the task of confronting this racism on its home ground, combatting it, and organizing white America for a new kind of world.”

Dorothy “Dottie” and Bob Zellner took that call seriously, though they wanted to continue to work through SNCC. Following the Peg Leg Bates meeting, the couple crafted a proposal to remain voting members of SNCC staff but focus their energies on southern white communities. “With much regret and emotion,” their proposal was denied. According to Cleveland Sellers, SNCC’s executive committee, chaired by H. “Rap” Brown, was unwilling for the organization to have white staff and for that reason turned down the Zellner’s proposal.

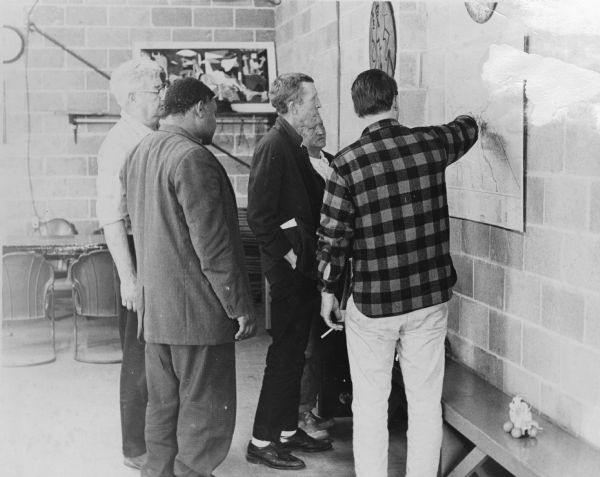

Strking union workers looking at a map during an organizing session, undated, Dorothy and Robert Zellner Papers, WHS

While they couldn’t work within SNCC, the Zellner’s were determined to uphold SNCC’s request that freedom-minded white people organize poor southern whites. They teamed up with SCEF to form the Grass Roots Organizing Work (GROW–sometimes referred to as “Get Rid Of Wallace”). “We want to begin the serious long-range effort to organize the white people in the south into an equal force in strength and similar in commitment to the movement now flourishing in the Black community … so that interracial coalitions, based on common interest, can be formed,” read GROW’s mission statement.

GROW seized its first opportunity to organize working-class southern whites in the summer of 1967. A union local (Local 5-443) of the International Woodworkers of America in Laurel, Mississippi, staged a wildcat strike against the Masonite Corporation after the company introduced a partial automation plan to reduce labor costs.

News about the strike passed through GROW’s headquarters in New Orleans. Before long, Bob Zellner, Jack Minnis, and other GROW organizers were making frequent visits to Laurel. The group first had to break through some of the racial animosity that they found there. Laurel was a known Klan hotspot, and while the union desegregated in 1964, many of white rank-and-file members were also members of the Invisible Empire. Following Zellner’s audacious lead, the GROW workers were forthright about their civil rights orientation and encouraged white union members to work with Black folks, if only for the sake of the strike.

As GROW workers embedded themselves in the local movement, they drew on their experience in SNCC to foster interracial grassroots organizing. They established a community center, called the Workingman’s Committee House, where they held integrated strategy meetings. These meetings often “started off very tense,” Dottie Zellner recalled, “but the conversation got to fundamentals and ended with sincere feelings of comradeship on both sides.” Jack Minnis, SNCC’s former research director, put his researching skills to use, poring over strike data, union laws, and Masonite corporate connections to find “flaws in the system.” He also helped the local union publish The Rights of Man, a weekly newsletter with updates on the strike.

The level of Black and white cooperation at the height of the Laurel strike was unprecedented in Mississippi. “Now instead of hooded night riders caravanning through the black community, the black and white unionists and their supporters would make a big show of drive through Laurel before heading out to the country for their meeting,” recalled Bob Zellner.

GROW continued its grassroots organizing work with white and Black folks for the next ten years. They continued to work with woodcutters throughout the South, who took on the region’s mammoth paper-making industry. They helped organize political elections and unions in other major Southern industries, like poultry and catfish processing. As Dottie Zellner noted, GROW’s work “proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that on a grass-roots level, it is possible to create working-class interracial coalitions. Period.”

Sources

Cleveland Sellers with Robert Terrell, The River of No Return: The Autobiography of a Black Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1990), 193-197.

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle, University of Washington Press, 2000), 449-452.

Dorothy M. Zellner, “My Real Vocation,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith Holsaert et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 311-326.

Bob Zellner with Constance Curry, The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement (Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2008), 300-313.

Shailly Barnes, “50 Years of Poor People’s Organizing: An Interview with Bob Zellner,” Kairos: The Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice.

Grass Roots Organizing Work (GROW) Proposal, undated, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.

“The Lessons of Laurel: Grass-Roots Organizing in the South,” 1968, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.