Bernice Johnson (Reagon)

October 4, 1942 – July 16, 2024

Raised in Albany, Georgia

Bob Zellner, Bernice Reagon, Cordell Reagon, Dottie Miller (Zellner), and Avon Rollins singing in Danville, Virginia, June 1963, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 66, Bleakbeauty.com

When the student sit-in movement erupted in the spring of 1960, Bernice Johnson was a student at Albany State College (now University). “All of us were excited about the sit-ins,” recalled Johnson, who “wanted to be involved,” especially after Julian Bond called from Morehouse University asking the students at Albany State to join the Movement. Johnson and a group of interested students decided “that we would combine campus issues with issues raised by the growing sit-in movement and take them to the administration.” The school depended on state funding, however, and Albany State president William Dennis let then know such protests would not be tolerated.

Johnson’s first brush with Albany State’s recalcitrant school administration didn’t deter her movement activism. It became “increasingly clear,” remembered Johnson, “that our actions would not always get an immediate response and we had to be willing to come back together and work out what our next steps should be.”

Johnson’s involvement in civil rights had begun a year earlier when she joined Albany’s NAACP Youth Council. “Our first effort was to get Negroes hired at a white-owned drugstore in a Negro neighborhood,” recalled Annette Jones, one of Johnson’s closest collaborators in the council. Their effort “was turned down flat,” but the group continued to meet to discuss conditions in Albany and worked with local organizations like the Lincoln Heights Improvement Association (LHIA).

When SNCC organizers Charles Sherrod and Cordell Reagon came to Albany in the fall of 1961, they found the students at Albany State ready for action. The two field secretaries started poking around campus, talking with students. Johnson remembered that Sherrod approached her and asked her the join SNCC. She was at first put off. “I told Sherrod that they needed to find another name for the organization … the term nonviolent did not name anything in my experience.” But something was happening “and I didn’t want it to happen without me.”

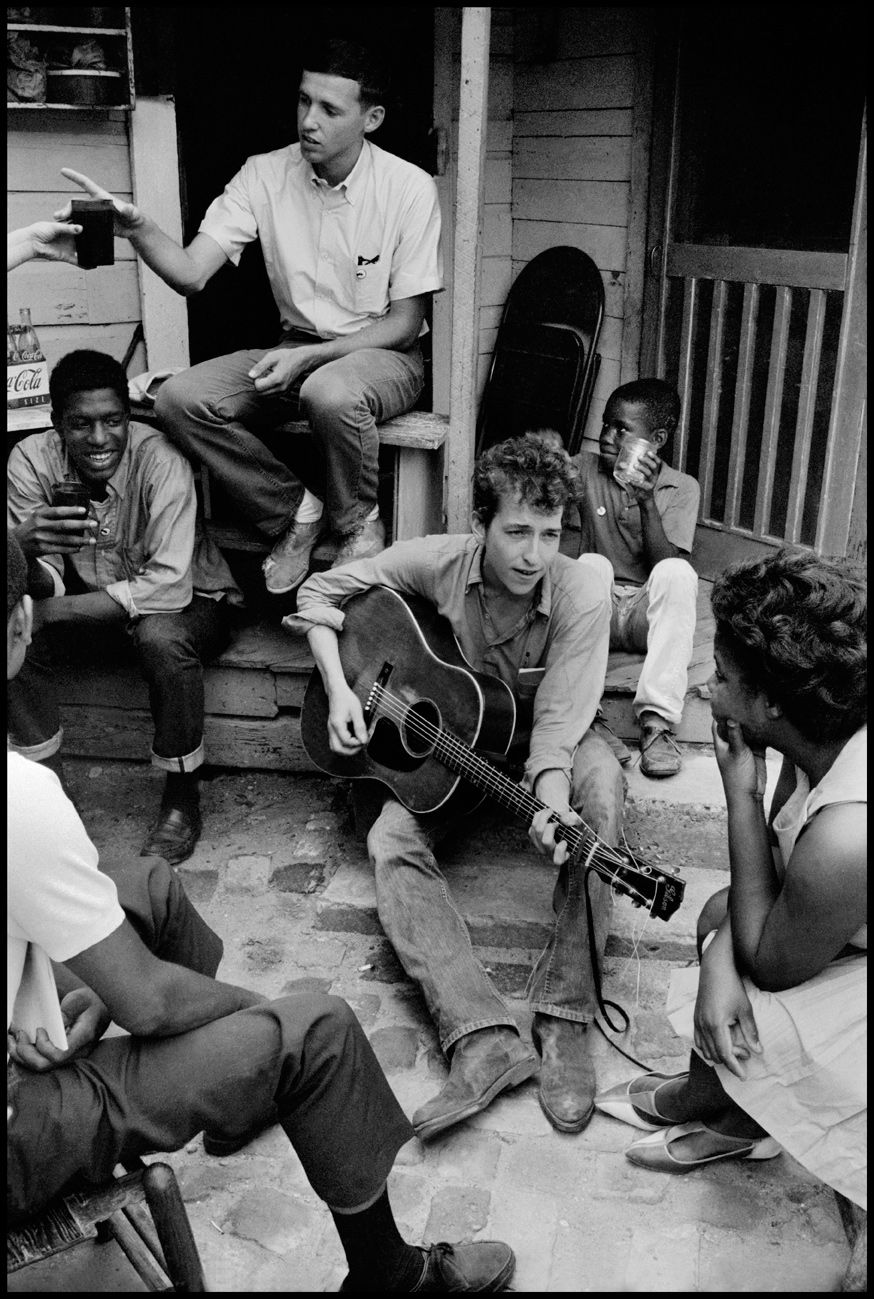

Bob Dylan plays behind SNCC office in Greenwood, Mississippi with Bernice Reagon listening, July 1963, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 110, Bleakbeauty.com

That November, the Albany Movement was organized in reaction to the arrests of Bertha Gober and Blanton Hall for testing the Interstate Commerce Commission’s ruling ordering the desegregation of interstate buses and trains. Johnson was now pouring almost all of her time into the local Movement. She served on the program committee, she planned meetings, and provided music. At one of the first mass meetings in Union Baptist Church, Johnson was asked to lead the participants in song. She started to sing “Over my head, I see Trouble in the Air,” but she quickly realized that “trouble” wasn’t the right word for the occasion. “So instead I put in freedom and by the second line everyone was singing.”

Johnson was suspended from Albany State for her activism. She spent a semester at Spelman College in Atlanta before joining SNCC’s newly-formed Freedom Singers in 1962. She married the group’s co-founder Cordell Reagon. The Freedom Singers toured the country to raise money for SNCC projects in the Deep South. The group also moved in and out of movement hotspots, using their music to provide a spark for local activism. “Basically the singing was the ‘bed’ and the ‘air’ of everything,” remembered Johnson. “I had never heard or felt singing do that on that level of power.”

In 1966, Johnson Reagon founded the Harambee Singers and in 1973, she formed Sweet Honey in the Rock, an all-women, African American a cappella group that sought to effect change and portray the Black experience through their voices. Johnson Reagon continued to use her powerful singing to allow others to study the African American oral tradition in radio, film, and concerts across the country.

Sources

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985).

Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, ed. A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

Bernice Johnson Reagon, “Uncovered and Without Shelter, I Joined this Movement for Freedom,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts By Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert et. al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 119-127.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, “Since I Laid My Burden Down,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 146-152.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, Pt F “Oh Freedom: the Music of the Movement,” We Shall Not Be Moved Conference, 1988, Trinity College.