Diane Nash

May 15, 1938 –

Raised in Chicago, Illinois

“Sherrod used to say, ‘If we could only find one person, the key is to find one more person other than yourself and then things will begin to roll.’ Diane Nash Bevel was responsible for the organization of a lot of us, including myself.” – James Forman

Diane Nash emerged from the sit-in movement in Nashville, Tennessee and became one of the most esteemed student leaders and organizers of the time. Born to a middle-class Catholic family in Chicago, Nash didn’t truly understand what segregation was until she enrolled in Fisk University. When she got to Nashville, “I started feeling very confined and really resented it. Everytime I obeyed a segregation rule, I felt like I was somehow agreeing I was too inferior to go through the front door or to use the facility that the ordinary public would use.” She began searching for an organization that was fighting segregation and discovered the nonviolence workshops that Rev. James Lawson was holding a few blocks from campus. There, Nash “got a really good, excellent education in nonviolence and how to practice it” and became an unwavering believer in nonviolence as a way of life.

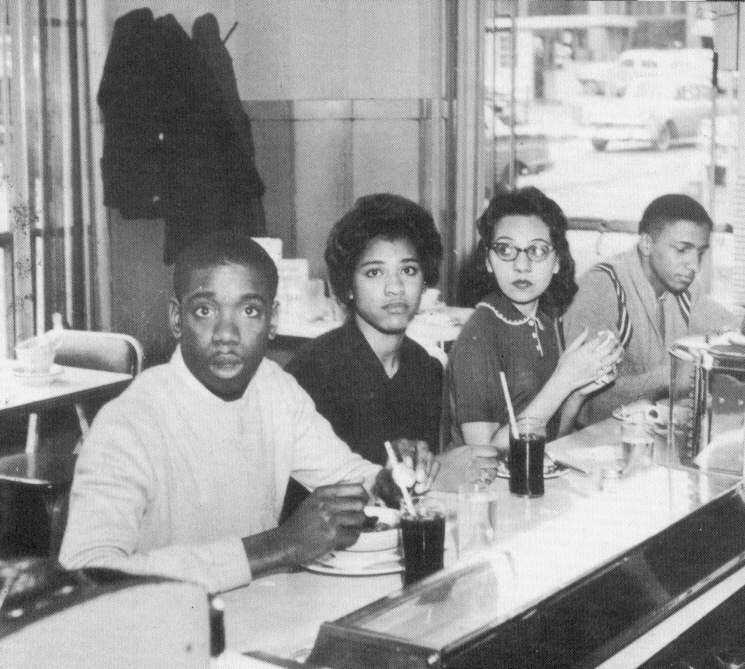

During sit-ins in Nashville in the spring of 1960, Nash and other members the Nashville Student Movement also sought to negotiate with restaurant owners to desegregate the lunch counters. A boycott of downtown stores by Black Nashville residents helped bring the white owners to the table. When owners admitted that they were afraid of a boycott by white customers if they desegregated, the Nashville group took them seriously. Nash and others recruited “some middle-aged white ladies who were very dignified-looking” who agreed to sit at the newly desegregated lunch counters for three weeks. “When you regard your opponent as a human being instead of somebody to fight,” Nash explained, “you can really work out problems.” The action staved off a boycott by white customers, and one of the restaurant owners even became an ally of the Nashville Student Movement’s desegregation campaign.

Nash was one of the founding members of SNCC, and few were more militant than she. On February 6, 1961, Nash and fellow SNCC leaders Ruby Doris Smith, Charles Sherrod, and Charles Jones sat-in in Rock Hill, South Carolina to support the “Rock Hill Nine,” nine students jailed after a lunch counter sit-in. Like the nine, all four refused bail. The SNCC activists believed that paying fines would only support the wrongness and injustice of their arrests.

When violence stopped the first Freedom Ride in Alabama not long after, Diane Nash was insistent that the rides continue. “The students have decided that we can’t let violence overcome,” she told movement leader Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, “We are coming into Birmingham to continue the Freedom Ride.” She later led all the rides from Birmingham to Jackson in 1961.

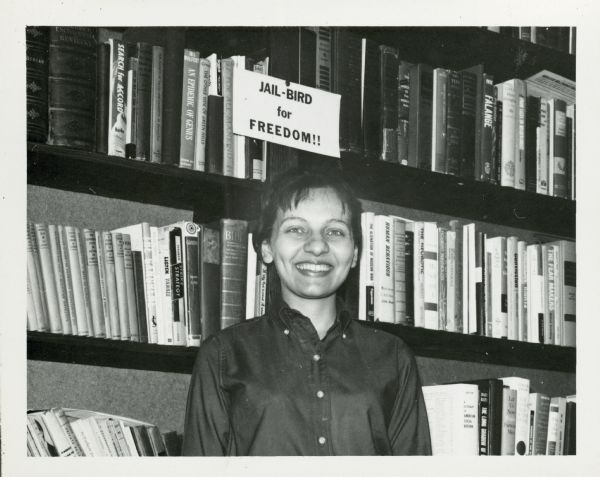

That July, Nash was arrested for conducting nonviolent workshops for black youth in Jackson. Nash told the judge she would serve the entirety of her two-year sentence. By that point, she had married Nashville movement colleague, James Bevel, and was pregnant with their first child. Nash served ten days on a contempt of court charge, but the judge never pursued the longer sentence. “I think they just decided it was likely to be more trouble than they had banked on.”

A fieldworker, strategist, and organizer, Nash went on to help organize the 1963 Birmingham desegregation campaign and worked alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and SCLC during the Selma Voting Rights Campaign.

Sources

Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954 – 1963 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988).

Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995).

Clayborne Carson, et al., The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Accounts from the Black Freedom Struggle (New York: Penguin Books, 1991).

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2008).

Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, ed., A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

Diane Nash, “They are the Ones Who Got Away,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012).

Lynne Olson, Freedom’s Daughters: The Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement from 1830 to 1970 (New York: Scribner, 2001).