Charles Sherrod

January 2, 1937 – October 11, 2022

Raised in Petersburg, Virginia

Charles Sherrod’s work as SNCC project director for Southwest Georgia reflects both SNCC’s evolution from nonviolent direct action to grassroots organizing and how the two are intertwined. In June 1961, he became SNCC’s first full-time field secretary.

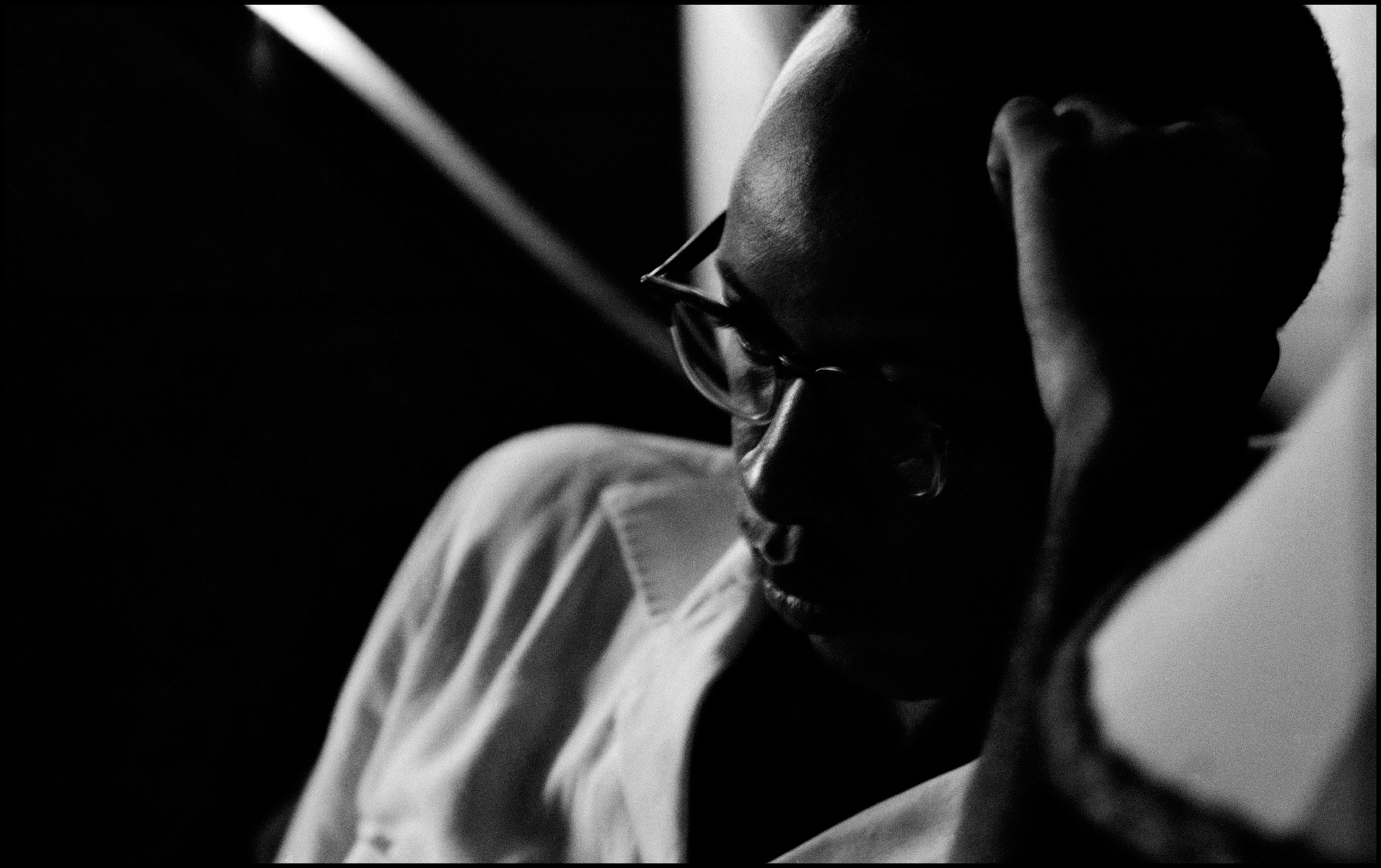

Charles Sherrod, the leader of SNCC’s Southwest Georgia Project, in Albany Georgia, 1962, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 33, Bleakbeauty.com

When the sit-ins began, Charles Sherrod was a student of religion at Virginia Union University, thirty miles away from his home in Petersburg. He helped staged local sit-ins at department stores in Richmond. He participated in SNCC’s founding conference, and after being arrested in Rock Hill, South Carolina with fellow student activists Diane Nash, Ruby Doris Smith, and Charles Jones, they pioneered SNCC’s Jail-No-Bail strategy, serving out the full 30-day sentence. In the fall of 1961, Sherrod and Nashville, Tennessee activist, Cordell Reagon, began working as SNCC field secretaries in Albany, Georgia, the regional center of Southwest Georgia. Notoriously known as a region of anti-Black terrorism as vicious as Mississippi, Sherrod hoped to use the small city as a base for voter registration activity in the surrounding rural counties.

Digging into Albany, Sherrod realized that breaking the people’s deeply ingrained fear was the first order of business. “It took me a long time to get an old fellow who said yessah and no ‘suh, and understand how to reach them,” he explained. But when he did, Charles Sherrod helped forge a community so empowered that Bernice Johnson (Reagon), one of the first local students to join SNCC’s efforts, called it the “the mother load.” “If you can imagine Black people at our most powerful point, in terms of community, and people-hood,” she said, “then that’s Albany Georgia.”

Perhaps because Albany was home to historically-Black Albany State College, though most adults kept their distance from the Freedom Riders, Sherrod found that “the children were unafraid. And it was the children who came to us.” And soon protests erupted. On Thanksgiving weekend 1961, two Albany State students working with SNCC were arrested for sitting in at the white waiting room at the Trailways bus station and refused bail. “As soon as these children were arrested, then all the love that their parents had … showed up at mass meetings because they came to see about these young people,” Sherrod explained. Increasingly adults threw their support behind their children, who were unafraid to protest. That winter, the Albany Movement filled the jails with demonstrators.

Charles Sherrod and Randy Battle visit a supporter in the Georgia countryside, 1963, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 114-115, Bleakbeauty.com

Although he had come to Southwest Georgia to develop a voter registration campaign, in Albany, Charles Sherrod found himself caught up in the protests, especially with the arrival of Martin Luther King Jr. and SCLC. But direct action protests grew into voter registration organizing in surrounding rural areas. As Bob Moses had in McComb, Mississippi, the Albany protest pushed forward a core of young people willing to work in the rural counties around Albany. They and Sherrod would trek down dusty dirt roads, talking to people about voter registration, slowly building local support for their effort. He welcomed the help of white volunteers. White and Black SNCC workers walking down street together demonstrated to the local community that whites were equal, not superior. Sherrod’s willingness to work with anyone willing put to their body on the line for the movement set SNCC’s work in Georgia apart. It made the project, what field secretary Bob Mants called, “ a proving ground for many of us.”

Charles Sherrod never left Southwest Georgia. When SNCC decided to expel its white members from decision-making in 1967, Sherrod resigned, stating, “I didn’t leave SNCC, SNCC left me.” He continued directing the Southwest Georgia Project for Community Education, and he and his wife, Shirley, established New Communities, a Black-owned cooperative farm in Lee County, that ran into the late 1980s. “The Southwest Georgia project still lives in south Georgia,” he said, “We’re still working.”

Sources

Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981).

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985).

Cheryl Greenburg, ed. A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

Faith S. Holsaert, et al., eds., Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012).

Shirley Sherrod, The Courage to Hope: How I Stood Up to the Politics of Fear (New York: Atria Books, 2012).

Interview with Charles Sherrod by Joseph Mosnier, June 4, 2011, Civil Rights History Project, Library of Congress.

Interview with Shirley Miller Sherrod by Joseph Mosnier, September 15, 2011, Civil Rights History Project, Library of Congress.

Interviews with Charles Jones and Charles Sherrod, undated, Freedom Summer A/V Collection, Miami University.

Our Voices: Strong People, featuring Faith Holsaert, Janie Culbreth Rambeau, Larry Rubin, Shirley Sherrod, and Annette Jones White, SNCC Digital Gateway.