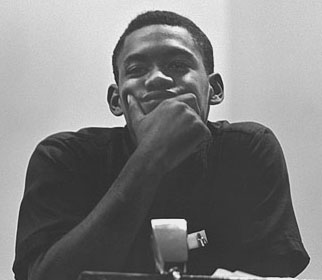

Curtis Hayes

February 24, 1943 – February 1, 2022

Raised in Chisholm Mission, Mississippi

As a young teenager, Curtis Hayes would hide in the bushes with the .22 rifle that he had received on his twelfth birthday, defending his family from the reign of white terror that flooded Mississippi in the mid-fifties. “It was like the river of no return for me, right there…I always knew somethin’ was wrong,” said Hayes, “As long as there’s people suffering oppression and injustice and poverty, racism and sexism, I want to be on that line that be punchin’ them in the nose.”

Hayes grew up in Chisholm Mission, Mississippi, a largely independent Black community named for an AME church that formed after World War II when a plot of exhausted land became available for a dollar an acre. Hayes’ family was one of 26 Black families that bought a piece, and they worked to build a community where everybody looked after each other. Hollis Watkins grew up in the same community.

When SNCC’s Bob Moses came to McComb, Mississippi in the summer of 1961, news of his arrival spread quickly through the small city and surrounding country. Hollis Watkins had just returned home to Chisholm Mission, and word of Moses’s presence in McComb reached him as Martin Luther King having come to town. Watkins rounded up a few of his closest friends, including Curtis Hayes, to try to meet him.

Dr. King was not in Mississippi, but the group met Bob Moses, “a normal, shy, quiet, serious man,” who talked to them about voter registration. Before long, Hayes and his friends were the foot soldiers for SNCC’s McComb project. They canvassed door-to-door attempting to persuade local Black adults to go to the county courthouse in nearby Magnolia to take the voting test.

By the end of August, McComb had become a focal area for SNCC’s work, and several SNCC organizers made their way to McComb and two other Southwest Mississippi counties–Amite and Wathall. In McComb, SNCC organizers hosted nonviolent direct action workshops, which attracted the attention of Hayes and Watkins, who were impatient with the slow pace of voter registration. “I said, ‘Damn, we could do this,’” remembered Hayes, and he and 15 or so local youths formed the Pike County Nonviolent Direct Action Committee. Hollis Watkins was president; Hayes was vice-president.

Taking the initiative upon themselves, the group decided to stage a sit-in. However, on the appointed Saturday, August 26, Hayes and Watkins were the only ones to show up at the local Woolworth’s. The duo still sat-in, and they were promptly arrested and sentenced to 34 days in prison “for bringing the sit-in movement to Mississippi.”

A few days later, Brenda Travis, Bobby Talbert, and Ike Lewis were arrested for trying to integrate the Greyhound bus terminal. After serving more than a month in jail, Travis, who was only fifteen, was expelled from the all-Black Burglund High School and sentenced to a year at a school for delinquent youths. Travis’s peers believed that the school’s punishment for student activism was overly harsh, and over 100 students marched to McComb’s city hall in protest on October 4. Hayes, Watkins, and the other SNCC workers who joined the students were arrested and charged with “contributing to the delinquency of minors.”

The arrests of the children, along with the nonviolent direct action protests, angered many of McComb’s Black adults. C.C. Bryant and other local movement leaders had invited SNCC to McComb for voter registration, not direct action protests.

This tension caused SNCC to leave McComb in December of 1961, not to return in any significant way until 1964. But Hayes and Watkins recognized the need for Mississippians to organize themselves and moved to Hattiesburg, Mississippi as SNCC’s first full-time staff who were native to Mississippi. There, with only $50 for six months, they helped Vernon Dahmer with a voter registration campaign.

Hayes remained a force in the Mississippi Movement throughout the sixties. He worked with fellow SNCC activist Charlie Cobb in Greenville and moved to Greenwood in 1963 after the shooting of Jimmy Travis. He finally made it back to McComb in the summer of 1964 for SNCC’s Freedom Summer Project, where he was wounded in the bombing of the local Freedom House.

Curtis Hayes (later Muhammad) was exemplary of the “homegrown organizers” that made SNCC’s work in Mississippi possible. “The Negro churches could not in general be counted on; the Negro business leaders could also not in general be counted on except for under-the-cover help,” explained Bob Moses. “Our feeling was that the only way to run this campaign was to begin to build a group of young people…who would be able to act as free agents.”

Sources

Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981).

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., On the Road to Freedom, a Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail (Chapel Hill, Algonquin Books, 2008).

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Robert P. Moses and Charles E. Cobb, Jr., Radical Equations, Civil Rights From Mississippi to the Algebra Project (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001).

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Laura Visser-Maessen, Robert Parris Moses: A Life in Civil Rights and Leadership at the Grassroots (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Interview with Curtis Hayes Muhammad by McComb High School Students, March 24, 2011, McComb Legacies Project, The Urban School of San Francisco.