2000

Organizing Veterans of the Movement

When in 1998 Stokely Carmichael traveled from his home in Guinea to Washington D.C. he was approaching the end of his struggle with prostate cancer. At a celebration of his lifelong commitment to Black liberation attended by hundreds of movement veterans, including all of SNCC’s past chairmen, a visibly weak Carmichael called for unity in the Black community.

Unstated but very much present in the dynamic of the event was the realization that age and illness could catch up to even the strongest of us. Increasingly, the necessity of SNCC people to begin telling their story was thought to be urgent by SNCC veterans. As well, the veterans could see that with mounting infirmities, there was a growing need to lean on one another for moral support at least. So, in the Bay Area, in Mississippi, in Chicago, in D.C., and elsewhere they began reaching out to each other to bring together what supportive resources they could to their movement community.

A conference for SNCC veterans at Trinity College in 1988; sit-in reunions in 1990; a large 1994 gathering Jackson, Mississippi during the thirtieth anniversary of Freedom Summer brought veteran activists closer together than they had been in many years. “We increasingly realize that whatever our differences then, and whatever our differences now,” SNCC veteran Mike Miller wrote, “we did something significant in the country and the world.”

In 2000 a group of movement veterans in the Bay Area coalesced around the idea of developing a network of support for their comrades who had fallen on hard times. They called it the “walking wounded” project, and people like Phil Hutchings, Betita Martinez, Mike Miller, Wazir Peacock, Jean Wiley, and Bruce Hartford, who had been loosely connected to each other largely because of geography, began to meet regularly and formally. They quickly realized that as Bruce Hartford, a former SCLC staffer, explained, “All of us were carrying hidden scars and emotional wounds that only others who had shared similar experiences could help heal.”

Telling their stories was a central part of their efforts to support each other. At that point, much of Civil Rights Movement historiography had the story wrong, focusing famous leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. or misleadingly putting white people at the center of the Movement. One effort led by Bruce Hartford created the Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement website, a now invaluable source of movement voices and documents. On the CRMVet (pronounced “crim-vet”) site, there exists an extensive collection of stories and documents where veterans of the southern freedom movement “tell it like it was, the way we lived it, the way we saw it, the way we still see it.”

Meaanwhile, movement veterans in other parts of the country were also looking for ways to tell their story and to share the lessons they learned.

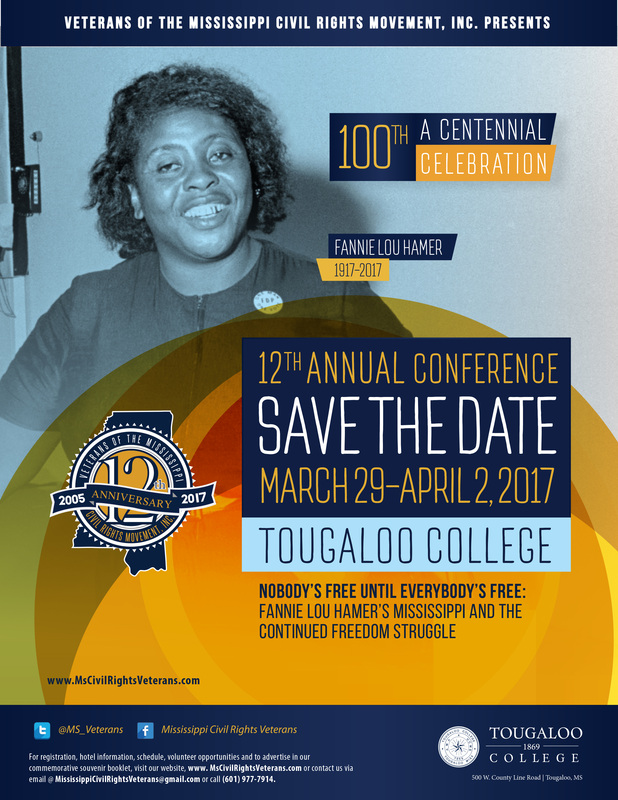

In Mississippi in 2004, Brenda Travis, Owen Brooks, Hollis Watkins, Jesse Harris, MacArthur Cotton, Euvester Simpson Morris, and Cynthia Woodall founded Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement. It is open to any participant in Mississippi’s movement and its mission is “documenting and telling stories of Civil Rights Veterans to empower the next generation and to continue the quest for freedom, justice, and equality.” They have been recording life stories, holding lecture series, and sharing their experiences with students and those who were continuing the work. They partnered with HBCUs, first Jackson State University and later Tougaloo College, where in 2014, they hosted the pivotal Freedom Summer 50th reunion and conference.

And in Chicago, Sylvia Fischer, Fannie Rushing, Mildred Forman and others, many former members of the Chicago Friends of SNCC, began similar work in 2004. SNCC’s James Forman died that year and the Chicago group established a history project to begin collecting oral histories with former members and local people involved in the Movement, eventually creating an archive of stories and memorabilia housed at Chicago’s Carter G. Woodson Regional Library.

In 2010, movement veterans came together in Raleigh North Carolina to celebrate the 50th anniversary of SNCC’s founding. Out of this gathering was born the SNCC Legacy Project. Its mission was to preserve the history of SNCC’s work and to assist today’s scholars, activists, and organizers in continuing the struggle for human and civil rights.

Sources

Mike Miller, “Renewing the Beloved Community,” Concept Paper for the Walking Wounded Project, September 2000, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.

Conversation with Bruce Hartford by Karlyn Forner, January 24, 2018.

Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.

SNCC Legacy Project Board Meeting, March 2018, Photograph by Kim Johnson.

SNCC Legacy Project Board Meeting, March 2018, Photograph by Kim Johnson.