Freedom Schools

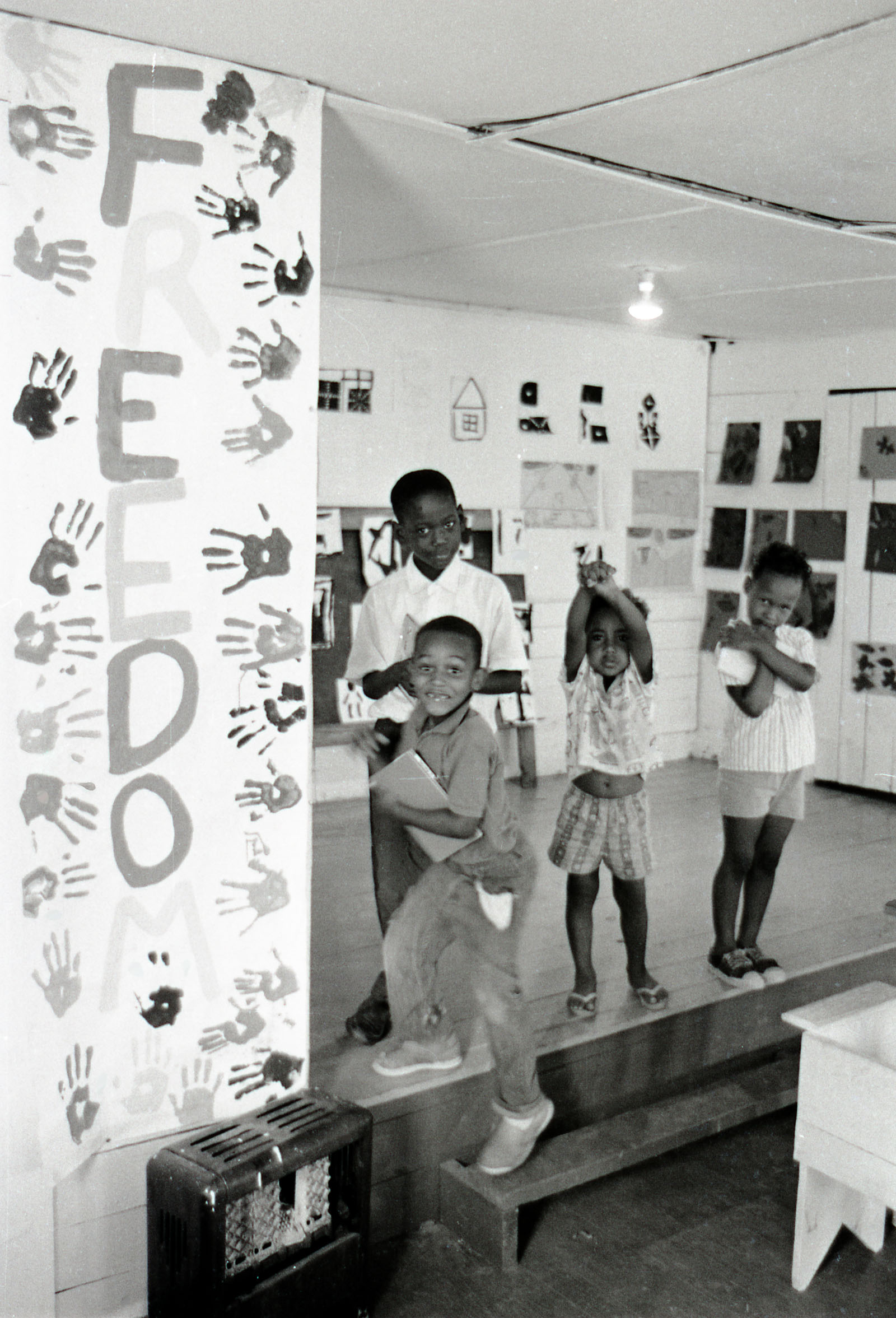

Children visiting exhibit of Freedom School students’ art work at the Palmers Crossing Community Center, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 1964, Herbert Randall Freedom Summer Photographs, USM

As planning for the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project got underway, a large question hanging over discussions was how best to utilize hundreds of incoming inexperienced volunteers. SNCC’s Charlie Cobb thought, “let’s use their education,” and in December 1963, proposed an education program–Freedom Schools–for young Black Mississippians, who suffered in an educational environment that was “geared to squash intellectual curiosity and different thinking.” Such a program would empower young people “to articulate their own desires, demands, and questions” and “to find alternative and ultimately new directions for action.”

Education had always played an integral role in SNCC’s community organizing work in Mississippi. Working closely with Annell Ponder from SCLC, SNCC field secretaries taught voter education classes to prepare Black adults for the state’s arduous registration exam. Bob Moses had begun a voter registration school on E.W. Steptoe’s farm in Amite County. June Johnson remembers that Stokely Carmichael developed classes for her and her peers in Greenwood. “And not just in history, he had people helping us with our maths.” SNCC workers were always concerned with the ways that public education hurt Black students and searched for ways to do something about it.

In the spring of 1964, SNCC created the Freedom School curriculum, which was rooted in the lives of young Black Mississippians. It had been designed by a committee of educators from around the country. Broken up into two parts–the “Citizenship Curriculum” and the “Guide to Negro History”–the curriculum was designed to help students examine their personal experiences with racial discrimination and understand their broader context in Mississippi’s closed society.

For Black Mississippians, the schools were the first time they had been encouraged to think and act politically, and to explore their creative impulses. Freedom School students read books and poetry by Black authors and listened to stories of Black resistance in past times. At the Holly Springs Freedom School, Pamela Allen taught her students about the Haitian Revolution. “When I told them that Haiti did succeed in keeping out the European powers and was finally recognized as an independent republic, they just looked at me and smiled,” she recalled. “The room stirred with a gladness and a pride.”

Freedom Summer volunteer, Barbara Schwartzbaum, teaching Freedom School class at Morning Star Baptist Church, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 1964, Herbert Randall Freedom Summer Photographs, USM

Many Freedom Schools were charged with energy and emotion as Black youth expressed themselves freely for the first time in a school setting. Students were inspired by the poetry of Langston Hughes and other Black poets and wrote poems about their own racialized experiences in Mississippi. After her Freedom School in McComb was blown up by a white terrorist attack, Joyce Brown expressed anger and determination in a poem entitled “House of Liberty”:

…I shan’t let fear, my monstrous foe,

Conquer my soul with threat and woe,

Here I have come and here I shall stay,

And no amount of fear my determination can sway…

The poem became the standard for the Movement in McComb. The local Black community found a new space for the Freedom School, which became one of the strongest in the state.

Freedom School students were also inspired to join the Movement and have their voices heard. Many schools created and distributed their own newspapers that covered the events of the summer, including the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). Students turned the Clarksdale Freedom School into an operating pressroom, recalled one of the teachers. “The place looked just like a newspaper office with people running in and out, with typewriters going, and newsprint everywhere … [the students] did most of the work and made most of the decisions.”

Towards the end of the summer, delegates from all 41 Freedom Schools traveled in Meridian for the final statewide convention. “The young people took over. They became the administrators,” recalled Staughton Lynd, a Spelman College history professor who was coordinator of the freedom school program. Participants drafted their own political platform for the MFDP. The platform covered everything from segregated public accommodations and housing to the educational and economic opportunities for young Black people. At the end of the convention, the delegation laid down the foundation for the Mississippi Student Union (MSU) to continue coordinated action against segregated schools and public accommodations.

Their experience at the Freedom Schools paved the way for many young Black Mississippians to join the Movement. For Jacqulyn Reed Cockfield, of the Meridian Freedom School, the “experience awakened an abiding desire in me to become knowledgeable of the entire civil rights movement.” She went on to work with the NAACP and the Urban League. For many students, the summer was a life-changing event.

Sources

Sandra E. Adickes, Legacy of a Freedom School (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005).

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University for Illinois Press, 1994).

Jon N. Hale, “The Freedom Schools, the Civil Rights Movement, and Refocusing the Goals of American Education,” Journal of Social Studies Research (2011), 259-276.

Jon N. Hale, The Freedom Schools: Student Activists in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

Jon N. Hale, “The Student as a Force for Social Change: The Mississippi Freedom Schools and Student Engagement,” Journal of African American History (Summer 2011), 325-348.

Florence Howe, ed., Myths of Coeducation: Selected Essays: 1964-1983 (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1984).

Elizabeth Martinez, ed., Letters from Mississippi: Reports from Civil Rights Volunteers and Poetry of the 1964 Freedom Summer (Brookline, MA: Zephyr Press, 2007).

Charles M. Payne, “Education for Activism: Mississippi’s Freedom Schools in the 1960s,” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, March 24-28, 1997.

Charles M. Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Daniel Perlstein, “Teaching Freedom: SNCC and the Creation of the Mississippi Freedom Schools,” History of Education Quarterly (Autumn, 1990), 297-324.

Joe Street, “Reconstructing Education from the Bottom-Up: SNCC’s 1964 Mississippi Summer Project and African American Culture,” Journal of American Studies (August, 2004), 273-296.

William Sturkey, “‘I Want to Become a Part of History:’ Freedom Summer, Freedom Schools, and the Freedom News,” Journal of African American History (Summer and Fall 2010), 348-368.

William Sturkey and Jon N. Hale, To Write in the Light of Freedom: The Newspapers of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015).