Becoming Organizers

In the early spring of 1960, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) executive director Ella Baker watched with intense interest as students attending historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) breathed new life into the Black Freedom Struggle. The sit-in demonstrations that began in Greensboro, North Carolina on February 1st had spread to over 80 communities in the South.

She wanted these activists to meet one another, and with money from SCLC, Miss Baker began planning a conference at Shaw University–her alma mater–in Raleigh, North Carolina to be held on Easter weekend. According to James Forman, who eventually became SNCC executive secretary, Miss Baker “felt there had to be some contact between the various student groups which had sprung up, or they might peter out of a lack of the nourishment of ideas and sustenance of morale that come from such contacts.” Over 300 students made their way to Shaw, and there, they formed the temporary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as a clearinghouse for sit-in activities across the South.

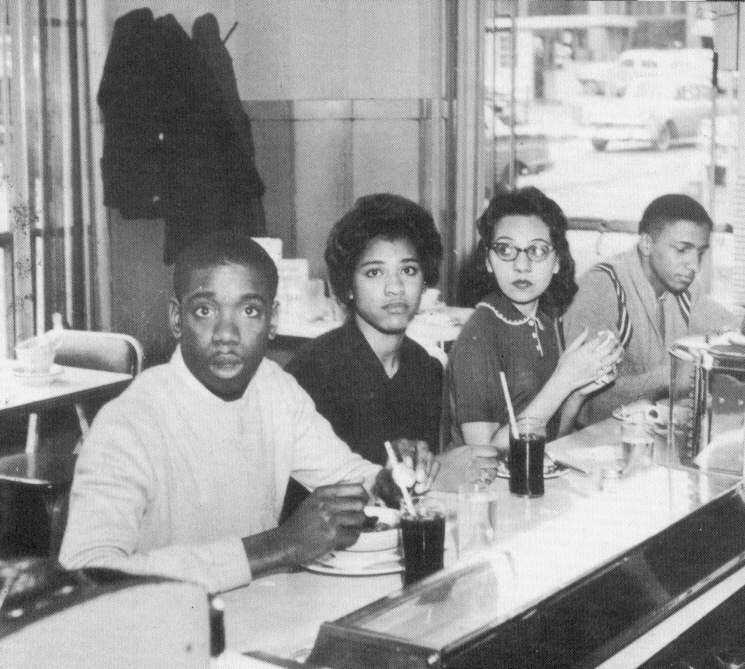

Nashville students, Matthew Walker, Peggy Alexander, Diane Nash and Stanley Hemphill, eating at a previously segregated lunch counter at the Greyhound bus terminal, undated, Gerald Holly, Nashville Tennessean, crmvet.org

During the conference, Miss Baker urged them to think of their Movement as “bigger than a hamburger or even a giant-sized coke.” She wanted the young activists to realize that it would take a full-time dedication to the Movement if they wanted to scourge America “of racial segregation and discrimination – not only at lunch counters, but in every aspect of life.” One important discussion that began during the conference and continued after it, was whether or not to stay in school or to take time off in order to commit to full-time to Movement work.

By the winter of 1961, 16 college students volunteered to take a year or more from school to work in the hard-core areas for subsistence only. They were dubbed “field secretaries.” Not only did these newly-minted field secretaries help bolster direct action campaigns, like the sit-ins and the freedom rides, but they also began organizing voter registration drives in the rural Deep South, where national civil rights organizations were afraid to venture.

Increasingly, voter registration became SNCC’s primary effort. Older movement leaders in the South encouraged this direction. Amzie Moore, a Mississippi NAACP leader, even attended SNCC’s second conference in Atlanta (October 1960) to put this idea on the young organization’s table. And in the late summer of 1961, Bob Moses, who in fact had already secured a master’s degree from Harvard, began SNCC’s first voter registration drive in McComb, Mississippi. Moses who was later joined by others in SNCC, worked closely with local NAACP people who guided them through the community.

Early SNCC organizers in Mississippi. From left to right: Bob Moses, Julian Bond, Curtis Hayes, Unidentified, Hollis Watkins, Amzie Moore, and E.W. Steptoe, Harvey Richards, We’ll Never Turn Back, 1963, crmvet.org

This work attracted local youths, like Hollis Watkins and Curtis Hayes, who quickly joined SNCC’s voter registration effort in McComb. Word also reached young people in Jackson, 70 miles to the north, who had been engaged in protests in the state’s capital; some had even been on Freedom Rides. With their energy, SNCC was able to expand its voter registration work into neighboring counties.

This core group–all native Mississippians–formed SNCC’s first field staff in Mississippi and would become key to the expansion of SNCC’s work in the state, especially voter registration efforts in the Mississippi Delta.

By 1963, SNCC had projects Mississippi, Southwest Georgia, and Arkansas, as well as a fully-functioning national office in Atlanta. The organization had 41 full-time employees, who were focused on voter registration in the Deep South. It was no longer a coordinating body for disparate student groups holding sit-in demonstrations, but a group of community organizers–an organization of organizers–organizing for black empowerment and political change in the nation’s most violent and repressive areas.

Sources

Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, ed., A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998).

Clayborne Carson, et al., The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Documents from the Black Freedom Struggle, 1954-1990 (New York: Penguin Books, 1991).

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed, How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016).

Stokely Carmichael with Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (New York: Scribner, 2003).

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985).

Faith Holsaert et al., Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012).

Howell Raines, ed., My Soul is Rested: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement in the Deep South (New York: Penguin Books, 1977).