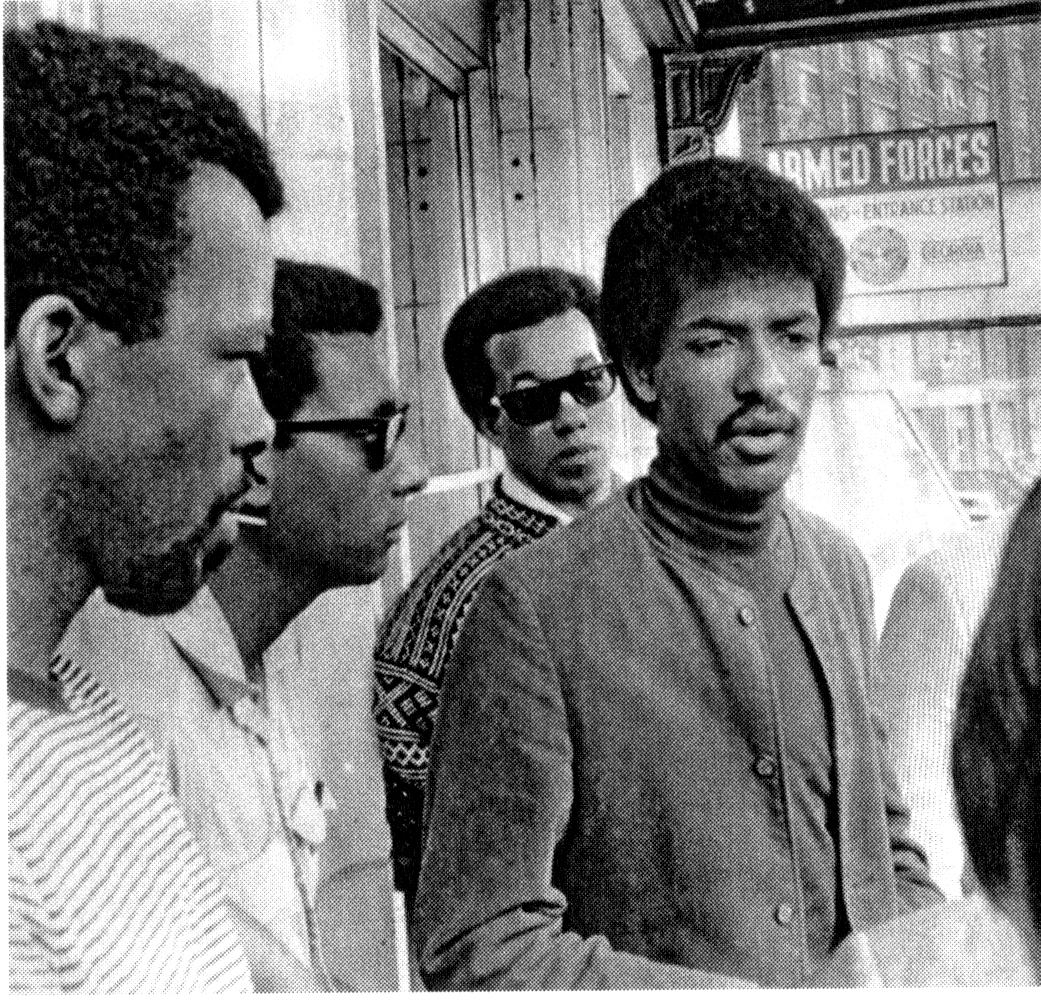

Cleveland Sellers

November 8, 1944 –

Raised Denmark, South Carolina

When Cleveland Sellers entered Howard University in the fall of 1962, he “expected to see everyone, students, instructors and administrators, passionately involved in the movement,” but instead he found a campus dominated by a “bourgeois” culture. Then he discovered NAG–the Nonviolent Action Group–the SNCC affiliate on Howard’s campus.

Sellers describes NAG as “a close knit group” of young activists fully committed to “learning about the Movement in the South and trying to address issues that needed to be addressed” in the nation’s capitol. In order to increase the visibility of SNCC’s voter registration work in Mississippi and Georgia, NAG members picketed the Justice Department, FBI offices, and even the White House. They also worked closely with Cambridge, Maryland civil rights leader Gloria Richardson. There, in that rigidly segregated, blue collar, Eastern Shore town roughly 50 miles from Washington, DC., Sellers’s commitment to the Movement crystallized: “I wasn’t worried about grades, school or dangers. I already decided … that the movement was my first priority.”

Sellers’s activism and dedication led him to Holly Springs, Mississippi in the summer of 1964, where he served as the assistant project director of the local movement. He was in charge of coordinating voter registration, Freedom Schools, and MFDP organizing in Marshall County. This included organizing Freedom Days, or days where local Black people congregated in Holly Springs to register to vote. Initially these Freedom Days were challenging to organize because Black residents were afraid of white retaliatory violence. By the middle of the summer, however, local people used Freedom Days to make a public stand for freedom and first-class citizenship. “There is nothing so awe-inspiring as a middle-aged sharecropper trudging up the steps of the voter registrar’s office clad in brograns, denim overalls and a freshly starched white shirt – his only one,” Sellers recalled. This kind of local response provided the motivation that pushed Sellers forward in the face of virulent white terrorism.

Sellers and his peers spent the summer working “doggedly from sunup to sundown” to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). They organized precinct, district, and state meetings and elected a delegation of Mississippi Blacks to challenge the legitimacy of the exclusionary Mississippi Democratic Party at the national convention held in Atlantic City in August. The group went to Atlantic City full of confidence, since the MFDP was clearly “legally and morally entitled to the seats.” Much to their dismay however, the national party offered the MFDP delegation only a compromise of two at-large seats and failed to recognize the party as the legitimate representative of Mississippi. The failure of the conventional challenge taught Sellers and others in SNCC an important lesson: that “morality wasn’t the basis upon which decisions were made. It’s political power at its rawest.” The Democratic Party was “not going to be the vehicle that we can ride in order to get freedom, justice, and equality.” And so SNCC began to look for new ways to ensure empowerment in Black communities throughout the country.

In the fall of 1965, Sellers was elected as SNCC’s program secretary. With his support, various members of SNCC began to seek new “levers of power” that could help Black communities in the North and South exert their political power to instigate change. Julian Bond won a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives, aided by SNCC organizers Ivanhoe Donaldson, Judy Richardson, and Charlie Cobb. And at the same time, Stokely Carmichael began to organize an all-Black independent political party in Lowndes County, Alabama, known as the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) with a snarling black panther as its logo.

Cleve Sellers was a key figure in pushing SNCC in the direction of organizing for concrete Black political power at the grassroots level. He was with Stokely Carmichael when that SNCC leader shouted out the slogan in Mississippi.

In the late sixties, Sellers returned home to South Carolina and became involved with protesting students on the campus of South Carolina State University. Police attacked students on that campus, killing four. Sellers was arrested and ultimately convicted for inciting to riot–a trumped up charged aimed at undermining his influence. He was imprisoned for seven months.

Twenty-five years later he was pardoned by the governor of South Carolina. In 2008 he became president of Voorhees College in Denmark, South Carolina, where he graduated from high school.

Sources

Cleveland Sellers with Robert Terrell, The River of No Return: The Autobiography of a Black Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC (Jackson: The University Press of Mississippi, 1990).

Our Voices: Emergence of Black Power, featuring selections from the SNCC Critical Oral Histories Conference, July 2016, Duke University.

Interview with Cleveland Sellers by Joseph Sinsheimer, March 30, 1985, Joseph Sinsheimer Papers, Duke University.

Interview with Cleveland Sellers by William Link, April 26, 1989, Greensboro Civil Rights Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Greensboro.

Interview with Cleveland Sellers by Gloria Clark, September 20, 2003, Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi.

Interview with Cleveland Sellers by John Dittmer, March 21, 2013, Civil Rights History Project, Library of Congress.