Judy Richardson

March 10, 1944 –

Raised in Tarrytown, New York

April 29, 1964 – 6 a.m. just got home with Betty. Birds are singing outside. The morning is really beautiful. Have about 7c to my name. Hope we get paid tomorrow. Will have to walk to work (about 2 miles), but it looks like it’ll be beautiful day. OH – John Lewis got arrested yesterday in Nashville. Bad cop brutality. Cordell on way there. Ruby Doris leaving tomorrow.

Working in SNCC’s National Office as Jim Forman’s secretary gave Judy Richardson a birds-eye view of the organization. She communicated with pro-bono lawyers, handled Forman’s correspondence and calendar, and covered the Wide Area Telephone Service (WATS) line that allowed SNCC workers to bypass local operators when reporting beatings and arrests. Between keeping these records, listening to Forman’s mantra of “write it down,” and witnessing the diligence of SNCC’s Research Department, Richardson recognized the importance of documenting the facts and her own experience.

Richardson grew up in Tarrytown, a small suburban town in Westchester County, New York, to an independent mother and a father who helped organize the UAW Local at the Fisher Body Chevrolet plant. Her father died on the assembly line when she was seven, and her mother had to care for the household and become the family’s sole support, challenging and nurturing two daughters on her own. Richardson received a four-year scholarship to attend Swarthmore College. There, she was swept into the Movement.

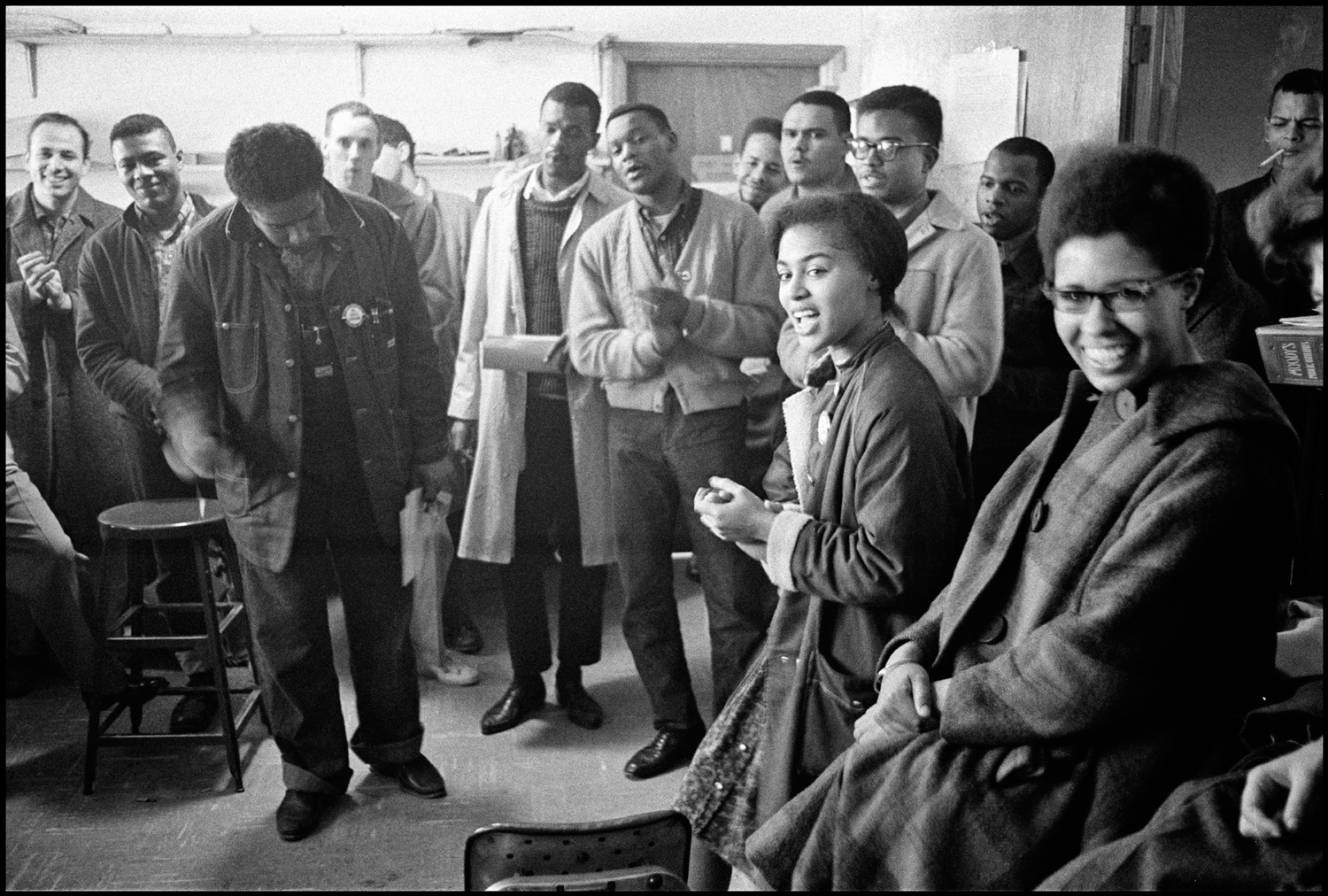

James Forman leads singing in the SNCC office on Raymond Street in Atlanta, (from left) Mike Sayer, MacArthur Cotton, Forman, Marion Barry, Lester McKinney, Mike Thelwell, Lawrence Guyot, Judy Richardson, John Lewis, Jean Wheeler, and Julian Bond, 1963, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 123, Bleakbeauty.com

Swarthmore’s chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was organizing students to join a local movement protesting segregated facilities on Maryland’s eastern shore. Seeing it in part as “adventure” Richardson boarded a bus to Cambridge, Maryland in the fall of 1962. She soon found herself in Cambridge almost every weekend, participating in demonstrations, going to jail, and meeting people like SNCC’s Reggie Robinson and Cambridge leader Gloria Richardson.

Hearing of her movement involvement, Penny Patch that spring suggested that Richardson take a semester off to work for SNCC. Patch, also a Swarthmore student, had been working with SNCC’s Southwest Georgia project. As a northern college student, Richardson was required to submit an application to SNCC’s administrative secretary Ruby Doris Smith. To her delight, it was accepted, and she moved to Cambridge to work with SNCC full-time.

When Richardson finally made her way to SNCC’s Atlanta Office in November 1963, what she saw was not what she had pictured. The office was rather shabby and located on the second floor of a beauty shop; 8 1/2 Raymond Street. Jim Forman, SNCC’s executive secretary, was there sweeping the stairs when she and Reggie Robinson arrived. After giving Forman a long hug, Robinson introduced the two. Upon discovering that Richardson could type 90 words a minute and take Gregg shorthand, Forman invited her to stay in Atlanta and work as his secretary.

Although Richardson appreciated her role in SNCC, she grew tired of taking the minutes at organizational meetings, and she noticed that only women were doing the minutes. So, in the spring of 1964, she and the four other women in the Atlanta Office decided to stage a sit-in. When Forman returned from one of his fundraising trips, Richardson, Mary King, Bobbi Yancy, Mildred Forman, and Ruby Doris Smith held a sit-in outside his office, singing Freedom Songs and holding signs saying, “No More Minutes Until Freedom Comes to the Atlanta Office.” Not long after, some of the men began taking notes at SNCC meetings.

Sit-in at Toddle House, December 1963, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 129, Bleakbeauty.com

Richardson moved with the National Office to Greenwood, Mississippi during 1964 Freedom Summer. Inspired by the Freedom Schools, she proposed a Residential Freedom School that would bring together Black high-school-aged students from northern cities with Black youth from southern SNCC projects. Her hope was that the movement-energized southern students would bring their growing sense of power to the understandably jaded northern youth. In July 1965, with SNCC’s support, she found the funds to bring a group to Chicago, Illinois and Cordele, Georgia, where she had worked.

When Stokely Carmichael and Bob Mants began organizing in Lowndes County, she joined them. She was then called back to Atlanta to manage the office for Julian Bond’s successful first campaign for the Georgia House of Representatives. After leaving SNCC in 1966 to return to college, she continued working with her SNCC comrades. In 1968, she joined former SNCC workers in forming Drum & Spear Bookstore in D.C., which for a time was the largest bookstore in the United States dedicated to literature from Africa and the diaspora. Drum & Spear had its own press, a radio show, and was at the forefront of the Black Arts Movement.

Richardson later became the series associate producer for PBS’s Eyes on the Prize series and co-edited Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.

Sources

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997).

Judy Richardson, “SNCC: My Enduring ‘Circle of Trust,’” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 348-365.

Judy Richardson, “Prospectus for a Residential Freedom School,” [1965], Judy Richardson Papers, Duke University.

Our Voices: Emergence of Black Power, featuring selections from the SNCC Critical Oral Histories Conference, July 2016, Duke University.

Judy Richardson, “The Way We Were: The SNCC Teenagers Who Changed America,” February 26, 2015, Women’s Voices for Change.

Interview with Judy Richardson by Jean Wiley, February 2007, Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website.