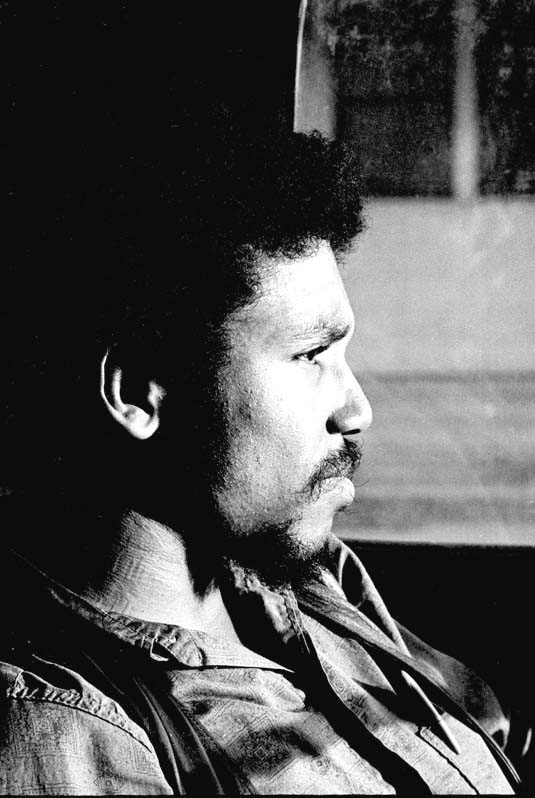

Bobby Fletcher

In the spring of 1964, while photographing a group of addicts who had formed a picket line in front of a bar on 137th Street in Harlem, New York, Robert “Bobby” Fletcher was thrown into a patrol car and arrested for disorderly conduct. “A black man can’t even take pictures in his own neighborhood!” he shouted. After spending a night in a city jail locally known as “The Tombs,” Fletcher decided, “If I’m going to go to jail for a bullsh*t like this, I’m going to make it really mean something.” He applied to be a Freedom School teacher in Mississippi and was soon attending one of SNCC’s training sessions for Freedom Summer in Oxford, Ohio.

Fletcher was drawn to photography at a young age. Frustrated that he couldn’t draw as well as his father, Fletcher decided to try his hand at the camera. His parents encouraged his interest. While he was a student at Fisk University, they sent him a subscription to the Saturday Review of Literature magazine, which often featured spreads of images by well-known documentary photographers. Fletcher attended classes at the Detroit Institute of Arts, where he learned about composition, scale, and perspective, all of which shaped his aesthetic and were incorporated into how he framed the world from behind the lens.

Although he had applied as a Freedom School teacher, word soon got out that Fletcher had a camera, and in Mississippi, Fletcher met Matt Herron and Cliff Vaughs, who were involved in the Southern Documentary Project and SNCC’s photography department. The need for photographers was great, since a main impetus of Freedom Summer was to shine the national spotlight on Mississippi. Fletcher spent much of the summer photographing independent, Black farmers of the Harmony Community in Leake County, agreeing to let SNCC use his photos for publication.

While making the trip from SNCC’s Atlanta office to Mississippi with a group of SNCC staff, Courtland Cox closed the door of the car saying, “We’re not victims, we’re really activists and that’s what we need to project.” For Fletcher, this was a turning point. “I began looking out for photographs that would show people more aggressive, more active, more assertive.”

Fletcher was a prolific photographer for SNCC. He went to the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). He photographed the Selma to Montgomery March, the development of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), and the Meredith March Against Fear, where “Black Power” was first articulated. The need for photographs was constant. SNCC’s photography department was getting requests from fundraising groups and support groups, from more established newspapers, and even magazines in England, France, and Italy.

In addition to trying to bring the realities of life in the Deep South to the national and international media, SNCC photographers worked to develop materials for the communities in which they were working. In 1965, Fletcher teamed up with Maria Varela, who he had previously encouraged to learn how to take photos for the adult literacy material she was developing, to create a series of filmstrips that showed how people were organizing themselves. Lightweight, easy to duplicate and disseminate, inexpensive, and accessible to the non-reading adult, filmstrips were seen as a great project for the department. One of the first filmstrips that they made, “If You Can Farm, You Can Vote,” was about how to elect farmers to the local Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) committee. “Now I understand why it’s important for us to elect people all over the country,” one farmer remarked after watching the filmstrip presentation.

In 1968, Fletcher was part of a delegation that went to Cuba to attend the Cultural Congress of Havana. There, he met artists, writers, and intellectuals from all over the globe, including members of the Mozambique Liberation Front, FRELIMO. His interaction with the southern African group fighting Portuguese colonialism led, after his time with SNCC, to a decision to go to Mozambique himself. Joined by producer Robert Van Lierop, Fletcher documented FRELIMO’s struggle for liberation, producing the film A Luta Continua (1972) and later O Povo Organizado (1976). Fletcher continued as a professional photographer and documentary filmmaker for years to come. He became an attorney in the early 1990s.

Sources

Leslie Kelen, ed. This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement, (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2011), 22, 239-240.

Maria Varela, “Time to Get Ready,” Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, edited by Faith S. Holsaert, et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 552-572.

Panel Discussion, This Light of Ours, Allentown Art Museum, January 17, 2016.

Unfinished Notes on the Status of the Heliography Department; November, 1965, Social Action Vertical File, Wisconsin Historical Society.