SNCC National Office

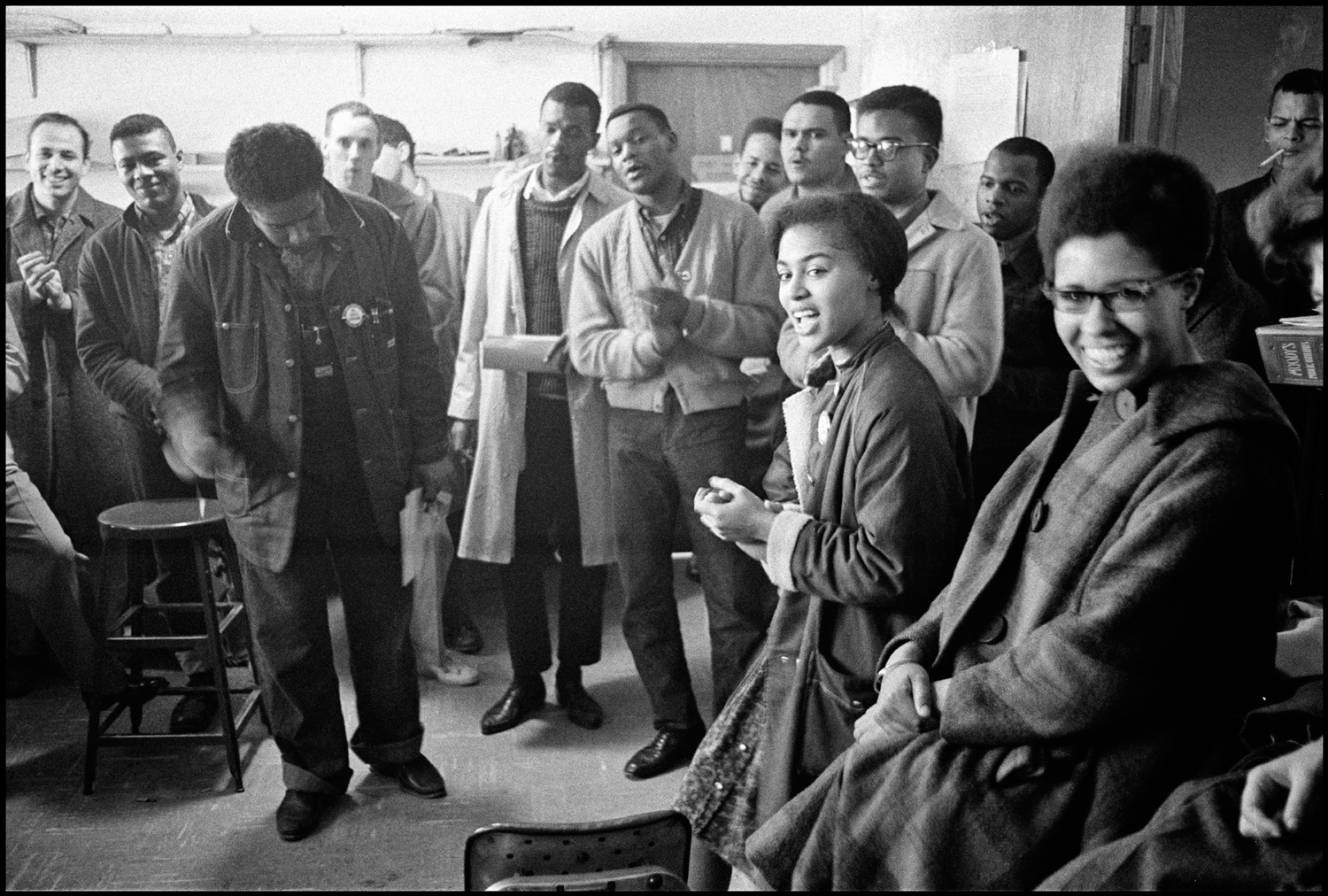

James Forman leads singing in the SNCC office on Raymond Street in Atlanta, (from left) Mike Sayer, MacArthur Cotton, Forman, Marion Barry, Lester McKinney, Mike Thelwell, Lawrence Guyot, Judy Richardson, John Lewis, Jean Wheeler, and Julian Bond, Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement 123, dektol.wordpress.com

SNCC’s National Office in Atlanta (also called “the Atlanta Office”) was set up to help organize the organizers. The National Office was there to help sustain the field staff, providing them with the tools and information they needed to do the work. Everything the National Office did was in service to the work.

As the nature of SNCC’s work changed over time, so, too, did the character of the National Office. What remained constant, though, was the central role the office played within the organization.

There was, however, an inherent tension. The field staff appreciated the essential work the national office did to support their work in the field. However the realities and needs of the office and the field were different. Field staff –- who were focused on the ever-changing and dangerous work of organizing in their communities — sometimes resisted the attempt to impose on them even a minimal bureaucracy (like monthly staff reports). Attempts at coordination could be like herding cats.

Also, the national office staff worked in less-violent Atlanta and lived in relatively comfortable apartments (Freedom Houses), which, though hardly luxurious, at least had indoor plumbing. Male and female staff stayed in separate apartments. Field staff stayed in one or the other when they were in town. The few married staff members had their own apartments.

The administrative genius behind the national office structure was SNCC’s executive secretary, Jim Forman. Though most SNCC staff workers were in their late teens and early 20’s, Forman was older (all of 33 years old in 1961), and had come to SNCC with a history of struggle. During much of SNCC’s life, the office — small and rather dingy – was a set of offices located above a beauty parlor near Atlanta’s five Black colleges.

James Forman remembered:

I felt a deep responsibility to the field people, who were not as safe as I was in Atlanta. It was always clear to me that our office in the city was, first and foremost, there to service the field and to provide a link between them and the outside world.

When you entered the office you entered a rather chaotic beehive of youth-led activity: workers taking calls from the field staff reporting in about a recent church burning; someone in communications writing up a press release and talking with the press; a SNCC staff photographer coming in from the dark room next door with photos of a recent demonstration; coordinators of the national Friends of SNCC calling around the network to check in and talk about support needed.

Then there were the various field staff workers (“field secretaries”) traveling through on their way to or from a field office: to pick up voter education materials, to discuss their research needs (who controlled the economics of a particular county or how best to apply pressure on key U.S. congressmen or senators from their state), or to attend an executive committee or national staff meeting in Atlanta. They’d also usually try to fit in some much-needed R & R in relatively safe Atlanta: going with SNCC office staff to hear Nina Simone, or Yusef Lateef, or Gladys Knight and the Pips at The Carrousel, the night club located in the back of Paschal’s, the famous the Black-owned restaurant that was just down the street from the office.

When a mailing had to get out, everyone went to the work room to fold, stuff and stamp the letters that would take news of SNCC’s activities around the country… and, hopefully, make the outside world care. And always – while they stapled and stamped – they sang. Freedom Songs were the sound track for the work, making it go more quickly. It also reminded the staff that even this mundane, repetitive work was important to the struggle.